A Viewer’s Guide to Mammography Evidence Ping-Pong

You could get a very sore neck watching all the claims and counter-claims about mammography zing back and forth.

You could get a very sore neck watching all the claims and counter-claims about mammography zing back and forth.

It’s like a lot of evidence ping-pong matches. There are teams with strongly held opinions at the table, smashing away at opposing arguments based on different interpretations of the same data.

Meanwhile, women are being advised to go to their doctors if they have questions. And their doctors may be just as swayed by extremist views and no more on top of the science than anyone else.

So here’s a viewer’s guide to help you make sense of play when the next new study appears and the batting begins.

First up: What’s with all the spin?

Spin is important in ping-pong. You would hope that matters of life and death would be settled without spin-doctoring, though. But the drama and emotion make that hard.

Around 70% of women aged 50-76 in the U.S. have mammograms. Ever since mammography started to take off in the U.S. in the late 1950s, Lerner points out it has had a “magic appeal.”

Around 70% of women aged 50-76 in the U.S. have mammograms. Ever since mammography started to take off in the U.S. in the late 1950s, Lerner points out it has had a “magic appeal.”

For others, though, mammography triggers ardent ideological opposition. Then there’s backlash and disillusion fueled by massive overselling of both the risk of breast cancer and the benefits of mammography. Perhaps inevitably, a strong counter-movement grew – and many of mammography’s critics succumb to the temptation of spin techniques, too.

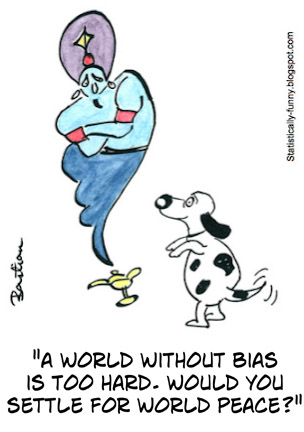

All up, there’s a colossal tangle of bias to get through when you consider breast screening – cognitive biases and statistical ones, too. It’s not easy to be, and stay, objective about mammographic breast screening.

The rules of the game

Data about screening often trips us into believing we can hold death at bay more than we really can. Bringing the date of diagnosis forward lengthens the time people live with their disease – their survival rate – whether or not their lives are extended. You can read more about issues like these in my previous post, The Disease Prevention Illusion: A Tragedy in Five Parts.

Proof that there’s a way to spot disease accurately isn’t enough. Finding disease early has to make a real difference to the outcomes people would have had if they weren’t screened. That means there has to be effective treatment that leads to results when it’s started earlier. And people have to be helped over and above those who would have been diagnosed soon enough anyway.

Proof that there’s a way to spot disease accurately isn’t enough. Finding disease early has to make a real difference to the outcomes people would have had if they weren’t screened. That means there has to be effective treatment that leads to results when it’s started earlier. And people have to be helped over and above those who would have been diagnosed soon enough anyway.

That means you need very big randomized trials that follow women for years to get close to some answers about mammography. By the time you have the data, tests and treatments have changed. On top of the fact that no study is perfect anyway, people who want to reject results have plenty of ways to dismiss the evidence that doesn’t fit their beliefs.

To help us get closer to solid, reliable answers, then, there needs to be a very strong accumulation of data from several big trials among different sets of women. Which means there are multiple, complex, idiosyncratic data-sets to analyze.

If you look at data that doesn’t come from adequate randomized trials, or you look at one or two studies in isolation, you’re unlikely to get a reliable impression. Cherry-picking information is an easy way, though, to convince yourself or others that what you believe is true.

Looking at all the evidence isn’t simple, either. With a lot of data and many complicating factors, researchers have a lot of options for analyses and conclusions. Yet more room for cognitive and statistical biases to spin play. With mammography screening for women at average risk of breast cancer for their age, it gets rather extreme: 10-fold differences between the numbers batted around is commonplace. Let’s follow the trial trail to see why.

Get to know the important players

The set of statistical tools that can examine data from groups of similar trials is called meta-analysis. (Catch up here on 5 key things to know about meta-analysis.) Over the years, the meta-analyses of mammography trials have outnumbered the trials. The first completed screening mammography trial began in 1963 – the last in 1991. You can see a good description of the key trials in Table 3.1 here.

There is one more trial underway in England. It’s testing whether there’s benefit in starting screening a bit earlier and going a bit longer. Women will be recruited until at least 2016. There’ll be no results from a new trial in women at average risk for their age for a long time.

The key players to watch out for are the meta-analysts whose work is the basis of new reviews and the claims and counter-claims about mammography. There are 3 main groups who have been doing meta-analyses: other reviews and positions are based on using one or more of these as their source on the key question of breast cancer deaths. (You can reach reports of the meta-analyses via links at my comment on the Peter Gøtzsche Cochrane review at PubMed Commons.)

The key players to watch out for are the meta-analysts whose work is the basis of new reviews and the claims and counter-claims about mammography. There are 3 main groups who have been doing meta-analyses: other reviews and positions are based on using one or more of these as their source on the key question of breast cancer deaths. (You can reach reports of the meta-analyses via links at my comment on the Peter Gøtzsche Cochrane review at PubMed Commons.)

Gøtzsche’s Cochrane review is the longest-running player. It’s been updated several times – the last time in 2013. No further updates are planned. (Cochrane reviews are published by the Cochrane Collaboration, an international organization that does and promotes systematic reviews of health care.)

Then there are the reviews by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Their first meta-analysis was done in 2002 and updated in 2009. An update is planned – and it will include data on newer screening technology. UPDATE: Draft new recommendations have been released for comment: no real change. And the USPSTF’s conclusion on 3-D mammography (tomosynthesis) is that there’s still not enough evidence. (20 April 2015).

The third key player is the 2012 Independent U.K. Panel on Breast Screening. They did meta-analyses of their own – and they compared their results to the other meta-analyses. The key data they compared did not change in the 2013 Cochrane update, so the numbers are up-to-date.

Now let’s look at the score-card

The snapshot of the meta-analysis below is for the risk of dying from breast cancer. It comes from the U.K. Panel. Each horizontal line represents one of the key mammography studies, showing the confidence intervals (similar to the margin of error).

Horizontal lines completely to the left of the solid black vertical line show a definite reduction in breast cancer deaths. If one of the study’s lines so much as touches that black vertical line, then it means no definite decrease or increase in breast cancer deaths. (One completely to the right would have meant a study showed a definite increase in breast cancer deaths.)

The diamond at the bottom summarizes all of the trials together. The diamond here is well to the left: a definite reduction in deaths of around 20%. The two lines that go right around the middle are the trials from Canada that recently reported longer term follow-up data. The new data don’t affect the results of this analysis. These trials had never shown benefit from mammography.

The three meta-analyses don’t come to a vastly different result on analyzing this question in these trials (15 to 20%). You use the relative risk reduction to calculate what groups of women who start with a different personal risk level might experience. If you have a very small risk of the disease in the first place, a 15-20% reduction will be very small, too. If your risk is higher, the chances of benefiting are greater.

But if they agree on this, how can it be that information based on the Cochrane review often talks about only 1 woman in 2,000 having a breast cancer death averted because of screening, while other results talk about 1 in less than 200?

Partly it’s to do with the Cochrane review concentrating on a particular subset of trials as more important than the larger pool: the two Canadian ones plus one. Others agree a subset is better quality, but not that the others are so bad you can disregard them.

But the major reason the numbers vary dramatically is because it depends on which age group they’re talking about. The group who end up in the Cochrane review tend towards younger women, and inevitably, then, to less benefit. Let’s look at the Independent U.K. Panel’s best effort to get data you can compare (Table 3 here).

In order to prevent one woman’s death from breast cancer, the number of women who would need to be invited for screening was:

- Cochrane review: 2,000 (including women aged from 39)

- USPSTF, for women aged 50 to 59: 1,339 and for women aged 60 to 69: 377

- Independent U.K. Panel, for women aged 55 to 79: 235

In order to prevent one woman’s death from breast cancer, the number of women who would need to be screened was estimated as:

- Independent U.K. Panel, for women aged 55 to 79: 180

A further key difference between people’s approach is what data they use on the chances of harm. That includes, in particular, getting false positive mammography results and getting treated for breast cancers that were never going to become dangerous to your health (“over-diagnosis”). Here’s another area where people will come to very different results.

The chances of being harmed aren’t fixed. It depends on the choices you make about how often you get screened. If you go every year, you’re more likely to experience harm than if you only go once every 2 or 3 years. So the data researchers choose on this is also going to be lower or higher based on their choices. The U.S. is looking at screening women for longer and more frequently than the U.K. So the estimate of number who benefit will be lower and the estimate of harm higher.

The Independent U.K. Panel calculated that if women go every 3 years from 50 till 70, roughly 1 in 180 could have a breast cancer death prevented. On that calculation, for each woman who won’t die from their breast cancer, roughly another 3 will be treated needlessly. And a lot more will have biopsies for false positives. The experience of a false positive is generally distressing, and the distress could take quite a long time to reduce. It doesn’t seem to increase clinical depression or anxiety, though.

There’s so much uncertainty here – even about what our individual risks of breast cancer might be. Whether you think the odds are worthwhile, is a personal value judgement. But hidden within that phrase “value judgement” is something else. Our personal cognitive and ideological biases have an influence on which set of data and arguments convince us, as well as the value we place on the chances of benefit or harm. Wishful thinking, denial, fear, fatalism – all that and more are pulling on our thinking.

We often worry a lot about the biases of who is giving us information. In the end, though, the biggest bias we have to deal with is our own.

~~~~

UPDATE on 30 October 2014: The World Health Organization (WHO), based on analyzing systematic reviews of trials and of observational studies, concluded that screening every two years is worthwhile in women aged 50 to 69 (if it’s a good screening program – and women make an informed decision to participate). Their estimates are similar to the UK Independent Panel.

Based on non-trial evidence – so they had less certainty about this – screening with mammography appeared to decrease the rate of mastectomy. That, they said, may be because of changes in surgical practice rather than screening itself. (The studies were comparing before screening was introduced, with after it was introduced – so that screening was not the only thing that was different.)

Their search for evidence was up to December 2012.

I’ll be commenting on major developments with reviews and meta-analyses on mammography at PubMed Commons.

More from me on early detection in my post on The Prevention Illusion: A Tragedy in Five Parts. Browse through all my posts on related themes.

More from me on early detection in my post on The Prevention Illusion: A Tragedy in Five Parts. Browse through all my posts on related themes.

Illustrations are my own (Creative Commons license), including cartoons from Statistically Funny.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.