Pentimento: Revealing the Women Obscured in Science’s History

Sometimes, beneath the surface layer, an artist’s earlier rendition of part of a painting can be glimpsed. Something was replaced, changed shape, or shifted. It’s called pentimento, because the artist changed their mind.

This weekend was the intersection between February’s Black History Month and March’s Women’s History Month. One-sixth of the year – not nearly enough for all the reverse pentimento it’s going to take to reveal the critical people obscured from view in science’s history.

Our lack of a full picture of the past affects our view of ourselves now. And some measure of improving inequities in the present requires us to address the tentacles of past unfairness. They are still entangling themselves in our lives.

During February I read for the first time about many women scientists I wish were so famous and honored that I’d always known of them. One is Roger Arliner Young.

The piece of photo in the above artwork is from the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, early in the 20th century. It’s the one I could find that was closest in time to when Young arrived there in 1927. That’s her at Woods Hole in the photo below.

“Not failure, but low aim is a crime”, she said in the yearbook at Howard University. She aimed for, and achieved, an extraordinary amount.

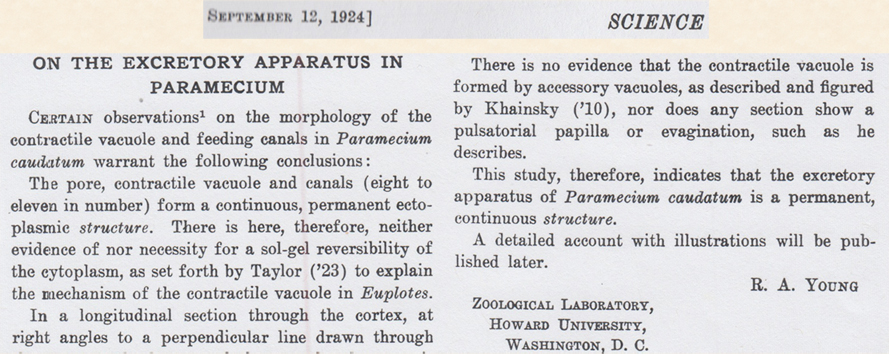

Young is the first African American woman to have her work published in Science (in 1924 – excerpt below).

She was the first African American woman at the Woods Hole Laboratory, too. According to historian Wini Warren, Woods Hole had “an interracially tense atmosphere”, but “Young was able to carve out a place for herself there”.

In 2005, Young was honored by Congress among a group of African American women who were first to gain a PhD in their scientific fields – hers in zoology.

The Congressional resolution stated that commemorating “top of the performance curve” achievements is crucial for young women to look up to, and encourage them into science.

Danielle Lee, a biologist who has herself been honored by the White House, wrote about Young’s inspiration when she was completing her own PhD: “It is her indomitable spirit that I channel today and every day as I near completion of my dissertation”. It’s not just Young’s achievements that Lee writes about: it is how much she had to overcome to get there.

Young was crushed by the unfair cards dealt her. Warren tells us that Young’s eyes were permanently damaged by the ultraviolet rays used in experiments she worked on at Howard University. She was poorly treated and badly betrayed by her mentor. In her words: “The situation here is so cruel and cowardly that every spark of sentiment that I have held for Howard is cold”.

She faltered in her first attempt at a PhD, but regrouped and went on to earn her PhD with a dissertation on “The Indirect Effects of Roentgen Rays on Certain Marine Eggs”. But it put her in debt from which she could never recover – and she was the sole support for her ill mother as well as herself. Away from Howard, her opportunities as an African American female scientist were limited. In the end, it broke her, emotionally and financially.

Lee writes that Young “never experienced any big fanfare and success”. Her achievements, and the burdens that she carried and was ultimately defeated by, are testament to Young’s strength, talent, and historical importance.

Across the Atlantic, Lucy Wills was a contemporary of Young’s. In many ways, her opportunities and life could not have been more different.

Wills was a pioneering hematologist, an early clinical trialist, and responsible for the first steps in recognizing folic acid. The kind of achievement for which others got to share in Nobel prizes. I wrote a biography of her several years ago, so I’m not going to re-tell her fascinating life story here.

Financially and socially independent – described by some as aristocratic – Wills led an adventurous life on several continents, with a lifelong friend, Margaret Hume. Wills was an early supporter of women’s suffrage, and spent successful years in local politics.

Wills achieved a particular recognition in life, that wasn’t something women could take for granted at all then – or even still now. Before it was called folic acid, the substance she was describing was called Wills’ factor. It sometimes still is. That’s how I first came across her name, actually, without even thinking it might be a woman. It was a delight when I found out Wills was a she.

In many areas of science, though, the contributions of anyone other than white males are squeezed out in death, as they were in life.

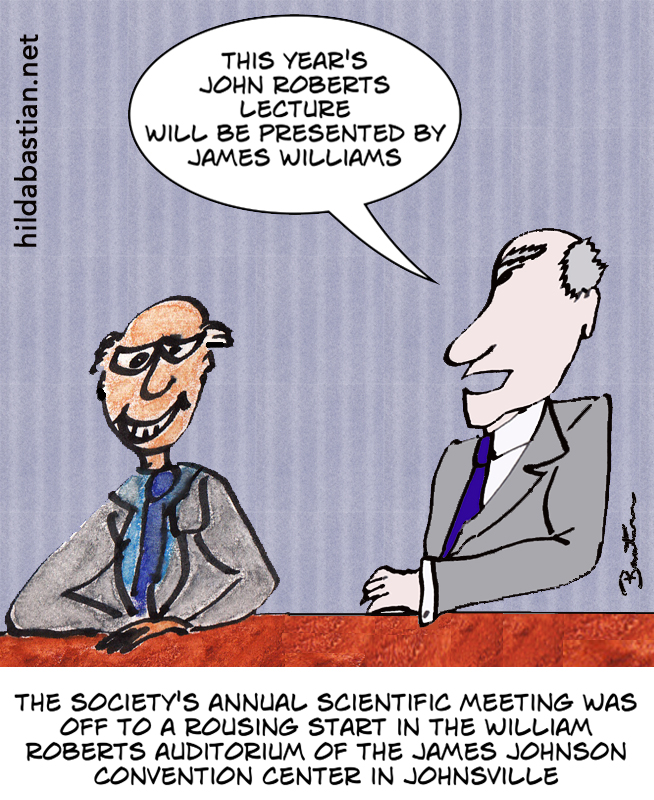

I recently wrote about the importance of more profile for women at scientific conferences. It’s not just who’s speaking at the podium that matters, though. The names of fellowships, prizes, lectures, buildings, meeting spaces – they’re heavily occupied by white males, too.

I was involved in quite a titanic struggle a few years ago to get a new prize at a scientific conference established, with a woman’s name. That it met with so much resistance was startling. But it needs to happen more, even if it’s difficult.

The Institute I work in is spread across two buildings on the NIH campus. In one of them, there’s an auditorium named after Ruth L. Kirschstein. She worked on polio vaccine and was the first woman to be a director of an NIH Institute. After she died, the auditorium was renamed in her honor.

Unfortunately, giving past minorities their due by reassigning honors probably won’t often be as warmly welcomed as that one was. But it matters.

When I walk past the Kirschstein auditorium, I give “her” a little smile. It always reminds me that we belong here, too.

~~~~

This Women’s History Month, we’re organizing an NIH Women in Science Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon. Follow on Wikipedia or me on Twitter if you’re interested in pitching in. There will be “to do” lists! And check out the other Wikipedia events this month.

Artwork at the top of my post: my cartoon woman is photobombing a segment of a mixed-gender, all-white, group photo of researchers from the Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, Massachusetts) in 1911: from Wikimedia Commons.

The excerpt of Young’s paper comes from: Young RA. On the excretory apparatus in paramecium. Science 1924; 60: 244.

Other information about Young comes from the chapter on her in Wini Warren’s book, Black Women Scientists in the United States (1999).

The photo of Lucy Wills is from her family’s archives, posted on Wikipedia.

The photo of Roger Arliner Young comes from the repository of the Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, Massachusetts).

The cartoon of the John Roberts lecturer is my own (CC-NC license). The names in it were inspired by a headline a few days ago in the Washington Post: “There are more men on corporate boards named John, Robert, William or James than there are women on boards altogether”. Any resemblances to any real Johns, Roberts, Williams or Jameses is purely coincidental. (More of my cartoons at Statistically Funny.)

I took the photo of the Ruth L. Kirschstein Auditorium at the NIH last week for this post (CC-BY).

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hi, Hilda:

Your pentimento reference in this blog post caught my eye. I use the same expression when referring to “implicit bias,” a concept which has received a lot of traction in the recent election cycle from candidates [Hillary] and pundits [“The Daily Show’s” Trevor Noah] alike.

Like pentimento our implicit biases live beneath the surface of our unconscious and yet very definitively shape our attitudes and our actions toward others.

Recently, I asked a group of medical residents at our hospital to journal their experiences and observations of implicit bias in clinical settings and to describe how those biases impacted patient care.

I received the following examples:

• A Caucasian boy with an abscess was nearly discharged from the ER with a sub-optimal medication because his parents were young and not well dressed, leading physicians to assume he was on Medicaid. It turned out he had private insurance and could afford the right drug for his condition.

• In another instance, a young African American woman was considered a “drug seeker” because of multiple trips to the emergency department complaining of headaches. Residents believed there was nothing really wrong with her but an attending physician suggested a full neurologic work up; an MRI revealed a brain tumor. Indeed, the woman had a physiologic cause for her headaches.

It seems, given the outcome of the election and the simmering antagonisms on both sides, we would do well to acknowledge our biases—see those pentimentos beneath the surface—and determine how we will address them. As my medical residents observed: implicit bias can be the difference between good care and poor care, even between life and death.

Lynn Todman, PhD

Executive Director for Population Health at Lakeland Health System

St. Joseph, Mich.

@LynnTodman