Tricked: The Ethical Slipperiness of Hoaxes

Hoaxes sure can stir up a lot of emotion, can’t they?

Hoaxes sure can stir up a lot of emotion, can’t they?

We tend to have a quick reaction to them, and they flush out differences in values quickly, too.

A few days ago, American journalist John Bohannon wanted to make a big splash with a post titled, “I fooled millions into thinking chocolate helps weight loss. Here’s how”.

It’s part of a publicity campaign started by two German journalists co-producing a documentary with German and French TV broadcasters. It’s a takedown of the diet industry, set to air next weekend.

As hoaxes go, this one is particularly complicated. And “hoax” is a pretty slippery concept, anyway.

At one extreme of a very broad spectrum, a hoax can be a straight-up crime – like fraud, and scams to swindle people out of money. Police “stings” hover towards this end of the spectrum, because they can veer into the crime of entrapment. (There’s debate about whether stings are as effective as other policing approaches, and whether they have only a very short-term effect or might increase crime.)

Way down the other end of the spectrum, a hoax can be a parody or performance art that’s snuck into the mainstream with just enough ambiguity that some people don’t realize it’s not “real”. It might be intending to jolt awareness, educate, or draw attention to ideas or a point of view. It’s not really intending to deceive.

This chocolate hoax is still unfolding, so we can’t have any idea where on the spectrum of seriousness or impact it’s going to land. We have been reacting to bits of a very stage-managed picture.

So far, the journalists have told us some details about four components:

- creating a website with an address and contact point for a fictitious research institute (in Germany);

- a real study (in Germany) on chocolate and weight loss designed to be rubbish science that would all but guarantee statistical artifacts that were marketable and misleading;

- a pseudoscientific article with authors’ names altered, claiming to show chocolate is a “weight-loss accelerator” in an English journal (pulled offline by the journal in the last few days, but available here); and

- a press campaign touting the study to bait journalists into covering it, including paying for testimonials.

Before we get to it, though, because it involves a genuine randomized trial, let’s look at what governs the conduct of this kind of research in Germany. Frameworks vary a lot internationally, even regionally. (Michelle Meyer, from Harvard Law School, has written a very interesting blog post on this hoax, from the perspective of the rules that would have applied if they’d done it in the US instead.)

According to Bohannon, the trial was “run” by a doctor (here and here). Update: The doctor was interviewed by his local paper, confirming his involvement.

Doctors are in a particular position of power and trust, with their patients, and in society. As long as they are acting in a medical capacity with an individual, they have considerable freedom.

However, when there’s an inherent possibility that another interest has the potential to come before the interests of the individual, then their wings may be clipped.

One of those areas is doctors doing human research. That’s not to say that research is always inherently against the individual’s interests. Just that the new dimension changes the “social contract”. It’s a position I’ve long agreed with, although many don’t.

In Germany, if a doctor (or certain others) is going to do research in people that might affect their mental or physical health, or with identifiable data, she or he must first lodge an application to an ethics committee. That details the study plan, numbers of patients, issues around privacy and data handling, how people will be indemnified against harm, and so on. There are additional research areas where this is needed, but that’s not relevant here.

With a non-drug study outside a university, the ethics committee responsible is from a state medical board like this one (called a “chamber”). German legislation makes the international Declaration of Helsinki binding for doctors too. (There are summaries of the German arrangement in English here [PDF] and in the background of this article.)

In this interview with Bohannon, he said there was no submission for ethical review (and in a later interview with Charles Ornstein from ProPublica he claimed there was no need for one). There’s been no public statement from anyone else involved on this question that I could find by internet searching in both German and English. Update: On 10 June, Gunter Frank, the doctor who according to Bohannon “ran” the study, confirmed in an email to me that there was no submission for ethical review, and it needed to be real people not actors: the broadcaster wanted real footage.

On the 28th, NPR reported asking Bohannon a follow-up question about ethics, but no answer has been reported yet. (Update: In the documentary that aired on 7 June, the journalists reported that they wrote the paper “totally without medical help”, although they had it reviewed by an ectotrophologist, a German type of nutrition scientist.)

Here’s how Bohannon and the two German journalists whose project this is, Diana Löbl and Peter Onneken, have described what happened. You can see Löbl and Onneken in action here in this short clip (warning, it’s disrespectful of overweight people to say the least).

Löbl and Onneken wanted to “reveal the corruption of the diet research-media complex by taking part”, according to Bohannon. They approached a medical scientist for advice about how you would do a scientifically rigorous trial, so they could make sure, she says, that they did the opposite.

Bohannon was called by the pair in December 2014. Löbl and Onneken “used Facebook to recruit subjects around Frankfurt, offering 150 Euros to anyone willing to go on a diet for 3 weeks. They made it clear that this was part of a documentary film about dieting, but they didn’t give more detail” (according to Bohannon). According to Löbl, she and Onneken did the recruiting, wearing white coats – because “clothes make the person”, she said – when they recruited 16 people in January. (Update: It was filmed for the documentary: you can see it here 5 minutes in.)

[Update] On 31 May, an interview with Frank, appeared in his local newspaper. In answer to reporter Ingrid Thoms-Hoffman’s question on whether the patients know they were part of a hoax, he said: “No, they had no idea when they came to my practice in January. Four days ago, I wrote to them and explained in full.” He reported they were recruited over a TV station’s Facebook page, and they were mostly from Heidelberg. (Note: all translations from German in this post are my own.)

When researchers intend to deceive people about the real purpose of a study, there are additional ethical hurdles. They are expected to justify why they can’t be told the truth. And to demonstrate there’s a potential for benefit that outweighs the burdens of inconvenience and potential harm people will be signing up for under false pretenses.

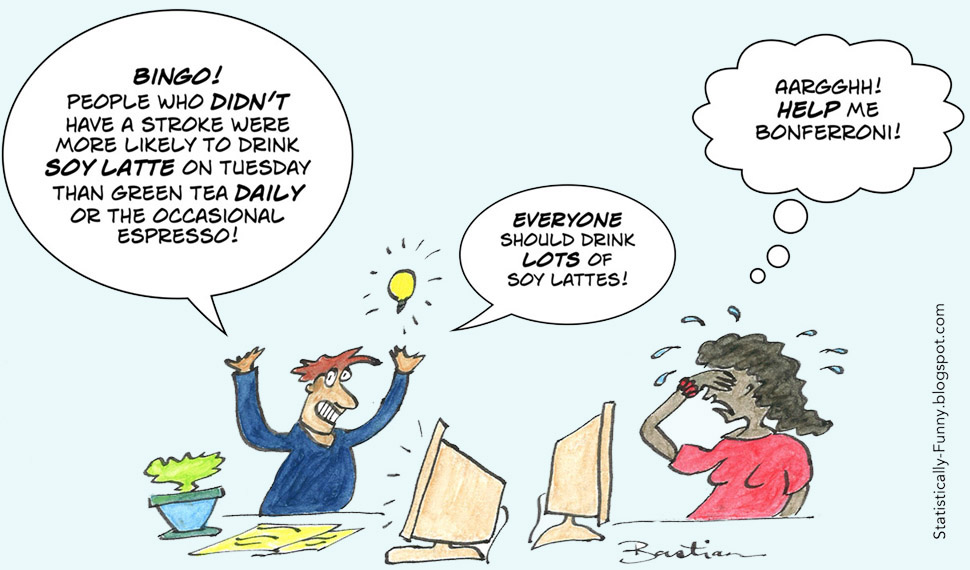

Well, there were no benefits to accrue from the study itself for the participants: when the ones who had to change to a “low carb” diet (2 out of 3 of the groups) had to eat more fat and protein and less carb every day, when they were all getting their blood tested, taking urine samples every day for weeks, logging their sleeping, eating, weight, moods etc every day – the data could never advance knowledge about dieting. Here’s an old post of mine on the risks of multiple testing. Each time you test, you run a small risk of striking a data anomaly. But the more you hunt, the more this risk snowballs.

The study couldn’t tell us anything we don’t already know about its true objective either, the diet research industry and journalism. We already know how easy it is to publish bad science, and that there’s low quality journalism. And actually, comparatively few journalists fell for it.

[Update] When asked by Thoms-Hoffman what he needed to prove with this study, since he had long been critical of the way dubious research is used to manipulate, Frank replied: “For me, there wasn’t anything more to prove. Nevertheless I was happy to join in. We live in a modern age, and a smart TV report makes this con trick easier for people to see”.

[Update] On 22 September 2016, Retraction Watch reported that the doctor has been fined for ethical violation.

If you’re going to deceive people, you have an ethical obligation about how you reveal the deception to them afterwards. That’s the subject of the question NPR has posed to Bohannon: just how are the 16 people finding out they were duped, if that’s what happened? (Here’s hoping it’s not by first seeing that YouTube clip.) [Update – Frank reported that he wrote to the participants four days before the 31 May interview. However, in the documentary, he’s filmed explaining it was a trick to one of the participants, and reporting that he told each of them one-on-one.]

[Update] And what about the data analysis? Bohannon wrote about it this way: “One beer-fueled weekend later and… jackpot!” When Thoms-Hoffman asked Frank what the result of the study was, he answered, “The one we planned to have, that is, that chocolate helps weight loss”. “And that was a lie?”, she asked. Frank’s reply: “Not directly. We used the usual research tricks to get the outcome we wanted. For example, we would ‘overlook’ an inconvenient result in a second measurement, some data were processed…the usual thing.”

[Update] Further details were reported in the half-hour version of the documentary shown on German television on 7 June. One of the research participants interviewed has diabetes. All 16 showed up to the follow-up session: they report that the data from 2 were dropped. They describe this is as done typically in scientific studies: drop-outs, they explain, means “we threw out the results that didn’t suit us”. In addition, before the final weigh-in, the people in the 2 non-chocolate groups drink a large glass of water to ensure they’d weigh more.

So was the study ethical or wasn’t it? One of the reasons many researchers feel very negative about these ethical review systems is that there’s often no consistency in the answers people come to on these questions. Meyer’s post goes into this important point in some depth. Maria Godoy’s report at NPR found contradictory opinions here too.

My personal position is that if we don’t agree with current standards for professional and ethical conduct, we can try to change the system, but we have to abide by it. If the standards are too low, we should aim higher – but we shouldn’t do less than is expected of us. To breach professional standards can be serious. And we can’t afford to erode public trust in doctors and health care professionals who approach people to participate in clinical trials.

Much was made in the publicity and documentary about conflicts of interest of others in the diet and media industry. Yet the participants in this episode demonstrated very little awareness of their own interests, be they in the success of the documentary itself, personal publicity-seeking, and book sales for one of them. And that’s the point of ethical review of research, isn’t it? To ensure that someone who does not stand to benefit from the exercise has checked that appropriate safeguards are in place. [Para added on 10 June.]

The argument in favor of this hoax is that it will have a benefit in terms of better journalism and perhaps even statistical literacy for enough members of the public to make it justifiable. Gary Schwitzer wrote: “I don’t know if Bohannon’s latest stunt will have any positive impact. Journalists and bloggers have already moved on to the next, much-quicker-than-24-hour, news cycle.” Meyer wrote: “What we need are feasible solutions to make these groups aware of this problem, not more evidence of the problem that perversely contributes to the problem itself.”

I agree with both of them. And there is some data to back that point of view: the real obstacles to better reporting are issues that won’t be affected by this, and even intensive training may not change behavior. Anyway, education has moved on from models based on shaming.

For what it’s worth, as a blogger who plugs away at statistical literacy writing and cartooning, I didn’t find the interest in reading my relevant posts as high as it gets when a media story challenges something people actually believed. (Last year’s spate of interest in resveratrol, for example.)

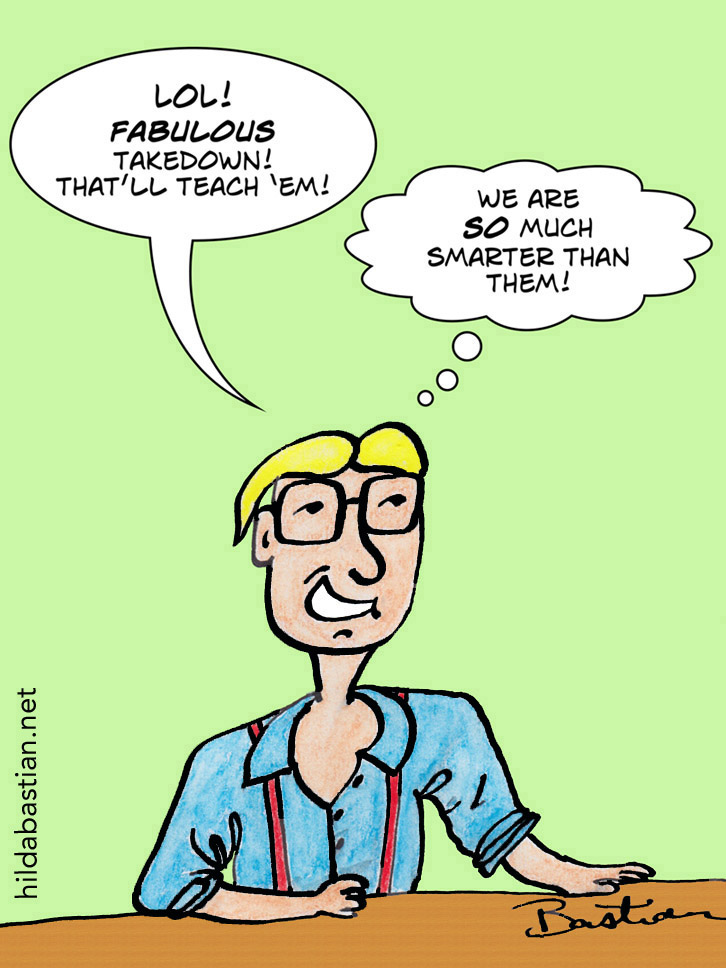

Faye Flam questions the grandiosity of Bohannon’s “I fooled millions” claim:*

Unless there was a suspicious spike in chocolate sales, it seems more likely that most people said “meh” or maybe even “huh?” but did not rush out to start a chocolate diet. For all we know from the evidence presented, 27 Americans were fooled. Bohannon’s claim plays to one of the most common and powerful biases – The desire to believe we’re smarter than other people. I’d never heard of the original study, but the exposure of the hoax is causing delight among my Facebook friends. People can’t resist reading about all those millions of inferior thinkers. Perhaps Mr. Bohannon fooled millions, or perhaps he fooled himself.

This gets us to the next slippery issue about this hoax: the journalists’ side. I think on balance the world’s journalists don’t get such a bad grade in terms of jumping to the string-pulling of the first campaign. But I wouldn’t give them high marks for their coverage this week.

First time around, the trio got some journalists from the infotainment end of the industry to dance the tune. This time, they’re getting the high end of the street to tell the story they want and promote their documentary, with very few sparing any words for the ethical issues.

I’ve mentioned some of the exceptions: in addition, Rachel Ehrenburg at Science News, Michael Hiltzik’s coverage at the LA Times, and Chris Lee at ArsTechnica really stand out. And Ed Yong led the charge on journalist ethics on Twitter. (The first I saw, anyway.) Seth Mnookin made a strong statement about falling for the click bait. (Update: And it turned out, Emily Willingham was posting about the same time I was.)

Hoaxing and the American press is the subject of a dissertation by Mario Castagnaro. It’s a fascinating look at the way the community’s attitude to hoaxes and journalists’ roles changed across several decades.

One of the things that struck me was that many see journalists’ hoaxes as a clever assault on the powerful. Yet, the more common hallmarks of the genre may be the ego and ambition of hoaxers – along with underlying disrespect for the public and other journalists.

Orson Welles’ famous War of the Worlds radio broadcast in 1938 was a cultural touchstone – and an unusually well-studied hoax. A revealing Welles’ quote relevant to his willingness to intentionally cause distress to bolster his career stood out for me: “I didn’t go to jail. I went to Hollywood.” Castagnaro singles it out as one of the turning points for society becoming more critical of hoaxes in the media – and expecting journalists to expose hoaxes, not undertake them. It was, he argues, key to the professionalization of journalism.

Clifford Irving’s Howard Hughes biography hoax in the early 1970s was another, changing direction from more gonzo journalism that had begun to encourage sensationalism, ego trips, and little regard for “objective distance” between the journalist and subject. (Irving did go to jail, because his hoax involved perjury and larceny.) Over time, hoaxing in journalism, Castagnaro argues, “came to be more readily associated with manipulation and the distortion of ‘truth’…a dangerous betrayal of public trust”.

I’m a cartoonist, so it’s no surprise that I am a big fan of parody and satire as a vehicle to communicate ideas. I don’t think there’s a fundamental breach of public trust there. Sure, occasionally people “fall” for an Onion story, but that’s not an abuse of power and a position of trust. We really need journalists to know the difference, and to call out abuses of power – not generate them.

~~~~

* Note added after original posting: Millions would have seen the original story – the front page of Bild Zeitung alone would be millions. Millions seeing is not the same as millions being fooled. (Bild Zeitung has since pulled the story from its online version, noting that the science was a hoax.)

Correction (2 June 2015): The original only noted the involvement of the German broadcaster, ZDF. The documentary was also co-produced with Arte, a French and German broadcaster.

The first version of the post did not specify the detail of the “low carb” diet intervention (updated 1 June 2015). I also added a link to an earlier report addressing ethics that I hadn’t seen when writing this post (by Chris Lee), and one written while I was writing mine (by Emily Willingham).

Updates from Ingrid Thoms-Hoffman’s interview with Gunter Frank in the Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung on 31 May were added on 3 June (translation link for an edit on 4 June).

Updates from the half-hour ZDF version of the documentary aired 7 June were added on 7 June; 1-hour version on Arte available on YouTube.

On 8 June I added a reference to an interview with John Bohannon by Charles Ornstein from ProPublica.

On 10 June I included Gunter Frank’s communication to me that there was no ethical review. I deleted a paragraph about there needing to be confirmation that someone other than the participants had ensured that people were treated ethically, and added one (noted).

On 22 September 2016 I added a link to Retraction Watch’s report of the doctor being fined for an ethical violation.

The cartoons are my own (CC-NC license). (More at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

Disclosures: I was (and remain) an outspoken fan of a journalist’s April Fool parody in 2006 (for an invented drug that of course could not be used, embedded with educational materials about overdiagnosis). My experiences bias me towards the regulatory side of this fence. I have spent time on national ethics committees in Australia, including working on revisions of guidelines for medical research. I’ve been a member of two ethics committees for journals: The BMJ several years ago, and PLOS One’s Human Research Advisory Group now. I’ve also participated in the regulation of professional conduct for medical practitioners in Australia. When I lived in Germany, I had close personal and professional ties with Ingrid Mühlhauser, the scientist these journalists consulted about research methodology.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Thanks for this Hilda – a very comprehensive assessment which, alongside pieces like Michelle Meyers, helps reveal and understand the more worrying aspects of Bohannon’s sting.

I still find it very concerning that the original spoof press release hasn’t been updates or removed (http://instituteofdiet.com/2015/03/29/international-press-release-slim-by-chocolate/). This smacks of a sting that has utter disrespect and disregard for the ultimate victims here – people grasping at straws for any piece of trusted advice that will help them address what are sometimes deeply personal issues. This disregard is reflected in the video (which I hadn’t bothered to watch before) – which I cannot believe is still available. Why hasn’t it been removed, or at least a large disclaimer added?

As you clearly show, the dialogue around the ethics of the sting (formalized through IRBs and similar, or our own assessments of appropriate/inappropriate behavior) is a complex one. An alternative framing that addresses many of the same issues is one of “responsibility” – I wonder if there are clearer answers to the question “was the sting responsible”?

I would argue “no”, as with each constituency group (subjects, journalists, publishers, scientists, consumers, and publics more generally) there seems little to no benefit, and the potential for lasting harm – not least in the erosion of trust between scientists and society.

It may well be that most constituents – as some have argued – take the misinformation and (if they were privileged to hear it) the reveal in their stride. But there’s always a tail of susceptible individuals who don’t conform to mean behavior or expectations.

In public health we take the well-being of these sub-populations very seriously. The sting perpetrators are still spreading misinformation through the spoof press release and video, and that same misinformation is still available without explanation on the internet. This may seem responsible to the sting’s perpetrators, but not to me.

Thanks, Andrew – those are very important points. I think considering the responsibility question is a good one. And yes, the issue of the current blast of publicity eroding trust in scientists is critically important. My own trust in people’s judgment took a shaking this week, to be honest – not because of the success of the lousy study, but when I saw the tenor of most response to the hoax announcement.

I agree about the continuing availability of the original deceptive materials – the same goes for the media outlets who haven’t taken it down yet. I was pleased to see that Bild Zeitung removed their story, replacing it with an apology to their readers for their mistake in publishing.

This is an excellent critique of the Bohannon “sting”. I fully agree that it crosses an ethical boundary and you have explained the perspective from the medical ethical boundary quite nicely. However, there is also a more basic ethical issue that I have not yet seen criticism of, and that is of the publishing ethics perspectives. John’s real name is not “Johannes” and it appears that the names of the co-authors might not be so kosher, either. Even the institute does not seem to be a real one. This implies that hidden conflicts of interest, and apparently undeclared issues related to the subject testing and approval were made upon submission to the journal. In other words, surely Bohannon et al. broke all basic rules of publishing ethics by submitting a false paper (or at least with false or incorrect, or invalid elements) to his so-called academic journal? I should note that I have been fiercely critical of Bohannon’s previous sting, which got him a nice paper in Science and I have always called for the retraction of that paper, or at least an expression of concern, because of the level of dishonesty and false information, required to get that “sting” completed. No matter what the final outcome is, in terms of the learning curve, I firmly believe that there is no place for this sort of dishonest behavior in science publishing. As for the retraction, good riddance. The key question is, how do we prevent “Johannes” from using his shenanigans to advance his “ethical” agenda in the future? Who will, in essence, be the next victim?

Thanks for adding that, JATdS: yes, it’s another important critical dimension. There are some more. I agree with your point at the end about prevention of more of this. I’d widen it, because if one person is rewarded so highly for socially harmful behavior, then others may decide it’s a good shortcut to “fame” as well. Hopefully, the negative consequences won’t only be on bystanders.

Hilda, you say this project “could never advance knowledge about dieting” and “couldn’t tell us anything we don’t already know about… the diet research industry and journalism [because] we already know how easy it is to publish bad science, and that there’s low quality journalism.”

Are you kidding? You might already know those things, but millions of other people don’t. Because they don’t, they are frequently misled into making poor decisions about their health, at best wasting their money, and at worst endangering their health.

This was not a “hoax,” it was a documentary journalism project — as the study participants were correctly told. It achieved an important goal. Exposing shoddy research and publishing standards might not advance your knowledge, because you’re an expert in the field, but it will surely help to educate many other people. Plus, it just might result in some small improvement in the aggregate quality of published papers and articles about health. That’s very worthwhile.

Bohannon’s exposé certainly makes some people uncomfortable, but he and his team have performed a valuable public service. Let’s not shoot the messenger because the knowledge he brought made people uncomfortable.

BTW, I love your “Help me, Bonferroni” cartoon! Do you mind if I use it on my web site?

I see what you mean, Dave, about it being known to some, but not everyone. Millions of others still don’t. It appears this is getting a lot of attention, but millions haven’t read the io9 article, for example. A single episode like this isn’t likely to be transformative – although if it proves to be, then it would certainly change the benefit/harm balance.

However, the bit you’re quoting is me saying that nothing could come out of that trial that added to knowledge about diet: it was designed deliberately not to generate reliable knowledge. All the rest has already been shown by other types of research: but that doesn’t automatically lead to everyone knowing it – and neither will this. They could have hoaxed the journal and the media with fake data too: they didn’t need to recruit patients into the caper.

As to whether it as a hoax: the journalists have said, in the German and American media, that it was, and that the participants were only given partial information by journalists masquerading (literally, dressed up in white lab coats). I couldn’t find the Facebook process they used to get people to come to that meeting with them, nor any other corroborating information, so I can only go by what they have reported. Secondly, you may not think it’s important for doctors to keep the law, but that’s neither here nor there: laws are binding, whether or not people think they are important.

I’m not sure what part of the message it is that you think people don’t like: I haven’t seen anyone disagreeing with it, and in my post, I certainly didn’t. It’s nothing new, and those messages are constantly going out.

Glad you like the cartoon! There’s a link to the usage terms at the bottom of the post: here it is.

Thank you!

It is common in social science research to hide the true goals of a study from the participants, if necessary for the study. This seems no different to me: it wasn’t really a serious study about diet, but it was nevertheless a serious study, which confirmed a correct hypothesis.

The study wasn’t medical in nature. It was more of a meta study: a study about studies. It was journalistic research. It was a study by journalists, as part of a documentary project, about shoddy scientific standards and what passes for “peer review” at some journals, and the propagation of junk science by the popular press.

As far as institutional review board approval, this might be a grey area. Since it wasn’t really a medical study, it’s not clear to me that seeking a medical IRB approval would have been appropriate. Is there such a thing as a journalistic review board? I don’t think so. I don’t think investigative journalists generally answer to anyone except their editors.

I do agree that, with rare exceptions, laws must be followed. But it is not obvious that any laws were broken in this case. I’m not a lawyer of any sort, let alone a German lawyer, but I think it is safe to assume that the authors at least did not believe that they were violating any laws.

Moreover, no one was harmed by their study, except some reputations which richly deserved it. So I’m willing to give the authors the benefit of the doubt w/r/t legal technicalities.

Pleased? The story was no less factual than 90% of what’s published in the Bild Zeitung. The reason they removed it was that they were embarassed being caught in a hoax someone else perpetrated – not that it was made-up nonsense. That they apologize for publishing it is revolting in its hypocrisy.

What makes this study more important to withdraw than newspaper-conducted manhunts or stirring xenophobic hatred with cooked up or cherrypicked “evidence”? It’s unlikely that the publication of this hoax actually led to anyone suffering bodily harm – quite the contrary to other things the Bild happily prints.

David, clinical trials are significantly qualitatively different – but either way, deception not straightforward ethically in social science either, and it wasn’t necessary either. Secondly, it couldn’t confirm a hypothesis about diet at all. It was designed to be bad science, incapable of proving anything. (Which they did very well: it was utter hogwash and so was the article reporting it – as it was intended to be.)

The study was medical in nature: it involved actions that would change physical parameters (making people eating more fat, for example, was part of the intervention), and taking blood etc.

Ignorance of the law is no defense. And a person practicing medicine should know the limits of their power.

We don’t know if anyone was emotionally or physically harmed. We do know there was a lot of inconvenience for them – and that’s enough to tip the balance on benefits and harms. And finally, I simply disagree that the rules applying to regulation of human experimentations are just technicalities for people to ignore at will.

Yes, Hydroxide, I was pleased that at least in this, they did, in my opinion, the right thing. It’s more than others have done. That’s not an endorsement of anything else they do or publish.

Ethics of sting operations?

Well, I think that it does not matter at all. If I submit a paper and it gets published, all (yes, ALL) responsibility is shifted to the journal that actually exposes my flawed or cooked-up research to the public, and to other scientists. The public health issues that follow (e.g. in the chocolate diet case) are also not my problem.

I may be taking an extreme position here, but in this case it was exclusively the journal’s fault. They got trolled by people who were better at their jobs than the journal’s editors – if the latter existed at all. There would have been reasons enough to reject the paper.

Also, journalists failed miserably. They also take up responsibility for what they write about – they just cannot point at the guys that feed information to them.

In the light of non-editor journals, no-peer-review publications, we should discuss hard about setting incentives right. Research published under free licenses (like CC-BY-3.0) is surely the way to go, as we cannot retract any publication anymore – the blame stays with the journal. Everybody is allowed to disseminate retracted papers for free, and point to the journal with a certain schadenfreude.

More troubling is journalism. There is no incentive at all to set the story straight. Critical thinking is rarely nurtured by many newspapers. Anybody with a high school diploma and some experience can re-hash information into a readable, enjoyable text, but it takes a journalist with ethics and genuine care to make people think.

Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast was not a hoax. It was a radio play heard at the regular time for the Mercury Theater company. It was Halloween eve. It was based on a book published 40 years before. It was written and performed by a genius and his friends; but anyone fooled had only themselves to blame. (As Hadley Cantril pointed out in his 1940 book “The Invasion of Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic,” most of those who panicked were fundamentalists who confused the show with the end-of-the-world prophecies they were familiar with from church.)

I used to think that about the Welles’ broadcast, too, David, until I read Castagnaro’s dissertation. I highly recommend it to anyone who is interested in this topic, piece of history, or Orson Welles – including understanding who Cantril is and where he was coming from.

Hilda, you wrote, ” On 22 September 2016, Retraction Watch reported that the doctor has been fined for ethical violation.”

However, Dr. Frank responded in comments there that he was not fined for ethical violation. Rather, he paid a small (€500) administrative fee, and the investigation was terminated, with no conclusion of an ethical violation.

I have not yet seen the finding, but at this stage, given the choice of believing journalists reporting on the outcome, or of taking this interpretation of what happened from Frank – who clearly has a conflict of interest here, I will take the journalists’ version. Here is a German journalist’s response to Frank’s claim that no ethical violation was found.

I have been in contact with further reliable sources in Germany who will be following up on this, and will update as more becomes available.

I disagree strongly with your position here. Of course this was a hoax: just because you think it was a valuable one, does not change its nature. When you watch the documentary, you see journalists dressed up and pretending to be some kind of medical personnel: it wasn’t just a hoax, it was quite an elaborate one.

There is absolutely no evidence that it was a valuable exercise: there is no discernible improvement in the quality of media reports of health, and I have seen no report demonstrating any positive impact on members of the public. There is no evidence to suggest that this kind of event has any durable educational effect, or could have a positive effect on journalists’ practices. Reading comment sections in both English-speaking countries and Germany about this at the time, there was, rather, some sign of harm: people expressing doubts that any medical research at all could be trusted.

Although there is much wrong with the quality of research, the portrayal in this documentary of what they said were common methods of data analysis was absurd – as were claims made by Bohannon in his interviews after. The participants are continuing to misrepresent, too, German law and professional standards around ethics. Anyone reading the comments at Retraction Watch needs to remember that some of the comments are being made by Americans referring to processes they experience in America, making the extraordinary assumption that what happens in America, is how things work everywhere else.

I can’t speak to the knowledge of the German journalists who were involved: nothing I saw showed that they understand the legal framework that applied to Frank and what they did. There is no sign that Bohannon made any effort to understand the legal framework of the country he got involved in – before, or since. Apart from anything else, this is an ethical issue here too. It is not just cultural arrogance at play. Anyone getting involved in research in a country other than their own has an obligation to be sure that they observe the ethical and legal rules of that country: and they have an ethical obligation not to lower their standards if the country has less stringent rules than apply to them in their own country.

In this instance, people have ventured into a country with a stricter ethical framework around medical practitioners than exists in their own. To anyone reading the comments at Retraction Watch I would urge you to remember – or read up on if you aren’t familiar with it – the history of medical experimentation in Germany that led to this country’s very serious efforts to ensure that doctors do not abuse the trust the community places in them.

Since you don’t seem to know anything about medical ethics, how would you know what ethical rules were or were not followed? It is very clear that the study was not presented to a ethics board. This is a violation, and that is why the doctor was fined.

As a medical statistician who has a great interest in ethics, I am simply stunned by this travesty of “science”. From the text of the blog post: “[Update] And what about the data analysis? Bohannon wrote about it this way: “One beer-fueled weekend later and… jackpot!” When Thoms-Hoffman asked Frank what the result of the study was, he answered, “The one we planned to have, that is, that chocolate helps weight loss”. “And that was a lie?”, she asked. Frank’s reply: “Not directly. We used the usual research tricks to get the outcome we wanted. For example, we would ‘overlook’ an inconvenient result in a second measurement, some data were processed…the usual thing.”

[Update] Further details were reported in the half-hour version of the documentary shown on German television on 7 June. One of the research participants interviewed has diabetes. All 16 showed up to the follow-up session: they report that the data from 2 were dropped. They describe this is as done typically in scientific studies: drop-outs, they explain, means “we threw out the results that didn’t suit us”. In addition, before the final weigh-in, the people in the 2 non-chocolate groups drink a large glass of water to ensure they’d weigh more.”

I don’t care what they think. This does not happen “typically”. They are describing fraud. This is not “typical research practice”.

I am an author on a weight-loss study. The study involved kids. The intervention was successful, except for one particular child. She was in the control group, and her results were very atypical. With her in the study, the study was not successful. With her out, the effect was quite significant. I was one of 2 statisticians. We spent maybe 3-4 meetings discussing this one single case. We stood firm – the main analysis was going to include this person. We agreed that a secondary analysis could exclude that case, but that the study would present ALL DATA in the primary analysis.

I find it repugnant and disgusting that this notion of “typical practice” is presented in the casual manner.

So, your point is that if you lie, make up stuff, entirely fake the entire project, the journal is the entity which should find this out? That’s idiotic, honestly.

When you submit a paper, you sign documents attesting to the accuracy of the data, the study, etc. If you lie, that is fraud. This entire study is fraud, and a travesty of fraud.

And your idea that we go to research under free licenses is truly alarming. Free license publications ofen have much weaker peer review, if they do any peer review at all.

Here is a quote from JAMA: Internal Medicine. It is substantially equivalent to that found in most journals that I am familiar with:

“The authors also must certify that the manuscript represents valid work …”

So you have no idea WTF you are talking about.

I wonder about the actual persons involved in this study. Is it possible that they gained weight? If so, and the weight gain was large, this POS study actively harmed these patients. Plus drawing blood can have problems. What if the patient was harmed by the blood draw (a low-probability event)? Who would pay for that?

I was addressing the above comment to Dave, not Hilda. I should have ensured that the pronoun reference was clear.

Thanks, Paul: I didn’t think you meant me.

Thanks for this Hilda – a very comprehensive assessment which, alongside pieces like Michelle Meyers, helps reveal and understand the more worrying aspects of Bohannon’s sting.

This disregard is reflected in the video (which I hadn’t bothered to watch before) – which I cannot believe is still available.