Winning! Or Is It? The Science of Winners’ Fate

Between the Olympics and a tumultuous U.S. general election, wanting to win really badly is dominating the airwaves at the moment. How does winning work out in the long run though?

We get occasional bursts of publicity about this or that group of winners living longer – Olympians, Oscar winners, Nobel laureates. But we hear about “winner’s curse” too. Let’s look at how those studies stack up.

This is a quirky area of the scientific literature. There are serious issues behind it, though. One is the role social rewards and prestige play in health and longevity – what Michael Marmot calls the status syndrome (and here: PDF).

Another is the issue of how survival statistics are calculated. Now that may seem like a straightforward issue. But it’s tricky.

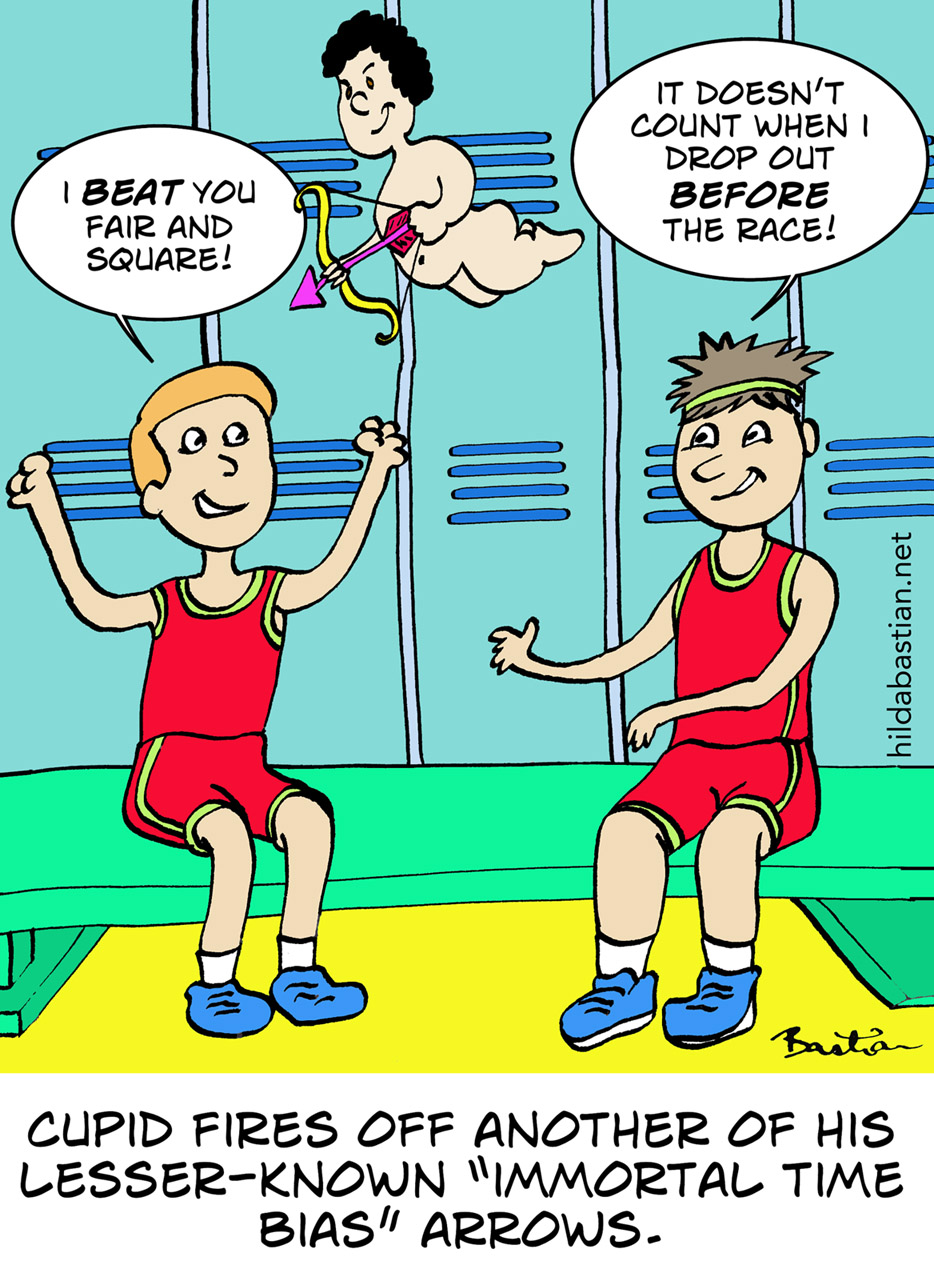

A claim that winning an acting Oscar gained you an average 3.9 years of life burst into a lively statistical debate a few years ago. It was all about what I’ve dubbed Cupid’s lesser-known arrow: immortal time bias. It makes people fall in love with unreliable statistical results.

The authors of the Oscars study didn’t dodge this arrow. “Immortal time” or a competing risk is when you compare an outcome in 2 groups – but the outcome gives one of the groups a built-in advantage.

A classic case happened in the 1970s. A heart transplant study compared death rates for people who had transplants with people still on the heart transplant waiting list. That stretch of time between being eligible for the heart transplant and getting it was a stretch of “immortal time”: you could not die during it.

If you died soon after being selected, you were of course in the no-transplant group. Analysis gets complicated when one group has a stretch of immortal time – or anything else that prevents them experiencing the outcome (a “competing risk”). (You can read more about this in my post at Statistically Funny.)

That’s what happened with the 4-year life advantage from an Oscar: they started the clock ticking at birth, not from the point when actors won their Oscar. When the data were later re-analyzed, the extra years of life pretty much evaporated [PDF]. (There’s an interesting discussion on both the statistical questions and post-publication review from the journal editors, Steven Goodman and Harold Sox.)

What about the “Oscar curse”? Michael Jensen and Heeyon Kim analyzed this (2015). Actually, Oscar winners go on to do more movies than their fellow nominees, and their careers decline more slowly. They don’t divorce more either – although their post hoc analysis showed the men divorce more, but the women don’t. Fan tip: there’s a figure showing a timeline of Humphrey Bogart’s Oscars and divorces. (More about post hoc analyses.)

There’s also the problem of low numbers, so this debate could rage on. Bruce Link and colleagues found a few years’ longevity advantage from winning an Emmy (2013).

So what about those Olympic medals?

I don’t think this is clear at all. Even with the summer Olympics, athletes in sports with a high risk of collision accumulate risks that could reduce their longevity (here and here [PDF]). And then there’s the risks of winter sports (more from me on that here).

One of the 2 studies above looks at Olympic medallists [PDF]. But they compare medallists with the general population, not their competitors who didn’t get medals. And they had a lot of missing data.

The other study looked at Olympic athletes but not medallists specifically. They used this database. It’s a font of interesting facts for Olympics fans. The youngest person to compete? In the summer games, Dimitrios Loundras in gymnastic at age 10 in the 1896 games. (Although his Wikipedia page says there was a 7-year-old in rowing in 1900.) The oldest? 72 years old in the 1920 games. (Winter games here.)

Other sporting awards are even less clear. A 2005 study found that Baseball Hall of Famers lived 5 years less than age-matched baseball players. But Link found no difference between nominees and inductees (2013). The award comes at the end of a career, and differences could have more to do with very successful baseballers’ lives than that single award.

What about that other big contest in the air at the moment? The U.S. Presidency.

I’m not sure if these 2 photos I picked do justice here. But the evidence supports the weight those years carry.

Jay Olshansky reckoned a U.S. President doesn’t age 2 years for each year in office as some claim (2011). But Gary Goldman pointed out you can’t really measure aging: and you’d expect the kind of person who becomes President to ordinarily have a longer life expectancy because of their socioeconomic status (2012).

Link’s findings on this were grim: getting elected President or Vice President reduced life expectancy by over 5 years compared with the “losing” candidates – but the number wasn’t statistically significant if you took out those who were assassinated (2013). There’s really a low numbers problem here.

Andrew Olenski and colleagues tried to get over that problem by looking at those who served as heads of government in 17 countries versus those who competed against them – presidental nominees or heads of competing political parties (2015). Their model counted life from last election, adjusting for life expectancy.

The elected ones tend to be older than their competitors. Taking that into account, it’s still bad: an average of 2.7 years of life less after leading a country.

That’s not something Nobel Prize winners have to worry about. Matthew Rablen and Andrew Oswald compared nominees with laureates for physics and chemistry between 1901 and 1950 [PDF]. They conclude (cautiously) that the Nobel also won people 1 to 2 extra years of life – and it didn’t seem to be about the (substantial) money.

So there you go, then. If you can choose between an Oscar, an Olympic medal, the U.S Presidency, or the Nobel – go for the Nobel.

You’re welcome.

~~~~

The cartoons are my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

Photo of Simone Biles at the 2016 Rio Olympics from Agencia Brasil Fotografias (via Wikimedia Commons).

Photo of Senator Barack Obama in 2007 from SEIU (via Wikimedia Commons). Photo of President Barack Obama in 2016 from the President of the Republic of Mexico (via Wikimedia Commons).

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.