Post-Truth Antidote: Our Roles in Virtuous Spirals of Trust in Science

It’s a classic vicious cycle. Post-internet, misinformation and ideas previously doomed to be only fringe-worthy spread far and fast. The faster misinformation travels, the less scrutiny it’s getting along its way. And the more of it that’s accepted by more people, the more the channels for unreliably-sourced information grow.

Until we get better at handling this, we may be an “information society”, but we won’t be a knowledgeable or wise one.

Although it’s quick and easy to get ourselves into this mess, there is no quick and easy way out of it. To counter this vicious circle, we need to build virtuous spirals of trust that can give trustworthy information more weight. Trust is powerful and it’s emotional. It’s not just a simple conscious decision, rationally arrived at.

Misinformation is widely socially distributed in digital networks now. Trust is widely dispersed too. So anyone reading this blog post has a role in making the situation better or worse to some degree. We are all part of the swarm intelligence or hive mind that people draw on to form their personal dynamic knowledge base in what Elisa Sobo and her colleagues call “Pinterest thinking”:

[S]elf-curated assemblages of ideas drawn from multiple sources using diverse criteria, held together only by connections envisioned by the individual curator…The idealized expert-generated, one-way, authoritative reign of science is over.

Sobo writes that just as the spread of the printing press led to the concept of having a nationality, the interactive internet has led to profound changes. We are integrated into the media now. We broadcast information and create it, too – social media posts, comments on websites, blogs.

It has been a bit worrying for science so far: even among those with science degrees surveyed in 2015, around 40% believed genetically-modified foods are unsafe to eat and didn’t believe human activity is causing serious global warming. But then, we haven’t had long to learn how to handle this social development. The iPhone only arrived in 2007, after all.

I wrote more about some aspects of this a while ago here. This post lists 3 ways I think we each have to get more serious, if we are concerned about science as a critical basis for knowledge in society.

1. Be serious about your spheres of influence – even small ones.

What we share and what we say to others could have an impact that’s bigger than we realize. We hear a lot about bubbles that we’re living in. But everyone isn’t living in only one bubble. Small circles of people are connected to other circles by members in common and those who are just plain good at connecting groups. Those people form bridges and can be conduits of ideas and information.

I find thinking of this in social capital terms useful – 2 types of “glue” between people. Bonding capital builds up inside a social group; bridging capital builds between them.

When we’re communicating, we could be strengthening bridging capital even when we’re in our bubbles, because of the “bridgers” among us. But we could be weakening it, too. There are all sorts of ways of firing up people who already agree with us. It’s very bonding. But how we do it is one of the things that will affect who trusts us – and how much effort is required by a “bridger” to translate or explain to others.

2. Slow down, but don’t only leave it to others.

If you react too quickly on social media or in a public setting, you risk contributing to the problem. Don’t think about sharing information as having little responsibility: every raindrop contributes to a flood. And the reliability of what you share affects how trustworthy you are.

Slowing down is a key step in protecting yourself from your own biases. (More on that in that earlier post of mine.)

But although we shouldn’t be too quick on the trigger, it doesn’t mean that inaction is a safe course. There’s a risk to that, too. Opinion formation is social. When it comes to controversies, if there is a spiral of silence in a group because people want to avoid conflict, that can become a problem, too, giving people a skewed impression [PDF].

3. Correct yourself.

Once you’ve circulated misinformation, you can’t just withdraw the effect it might have had. It’s a bit like the problem of a newspaper booming an error in a headline on its front page, and then having a little correction weeks later, isn’t it? Still, we need to try to face up to correct our own personal records, and to guard against being defensive when we’re wrong.

Now that we are part of the media, in effect, we share in its responsibilities and limits. How well a media outlet deals with its mistakes can affect how much it’s trusted – and the gap between consumers’ and media insiders’ perception of how scrupulously they correct themselves may be a factor in distrust of journalists [PDF].

If you are a scientist, then contributing to the accuracy of the scientific record is extremely critical to the trustworthiness of science.

Science obviously cannot correct itself: it requires scientists, editors, and research integrity entities to do that. And if anything, many if not most, both avoid correcting the record and don’t make anywhere near enough effort to ensure they don’t perpetuate error (see for example here and [PDF]).

We’re talking a lot these days about science’s “reproducibility problems”. I think that’s a euphemism for unreliable science and unreliable publications. Because most people don’t have the skills or time to detect unreliable data before sharing it, the onus is on the scientific community to make meaningful progress in improving the quality and integrity of research.

Truth is only one of the values that matter. The consequences of our societal vulnerability to misinformation can be severe and long-lasting, and far more so for some than others. Roopika Risam wrote:

In the Trump era, the contribution I have to make won’t come from my research, as social justice-oriented as it is, but from my work preparing teachers for their careers. In the face of an immense feeling of hopelessness, I can see the possibility of exponential influence – on my students, on their students, ad infinitum. It’s both a comfort to see a way forward and a humbling responsibility. We must get this right. The future depends on it.

That’s profoundly important. Many years ago, when I was in a community leadership role and national political events took a disastrous turn, my thoughts crystallized around a metaphor I found valuable: the bushfire. There’s a crisis and immediate needs and extreme vulnerabilities.

But there’s also work to do in ensuring the conditions for quick and robust regeneration after the crisis has passed. We have to re-double our efforts to protect and nurture the people and institutions we need in the future. It’s on each of us.

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world.

Eleanor Roosevelt (1958)

The discussion in this post continued into another post after comments.

Postscript:

Are we going to be hearing this word endlessly now – or will we get post, post-truth?

Use different criteria, of course, and post-truth might not be your word of the year. Part of the reason it’s Oxford Dictionaries’ choice is that so many people looked it up, not sure what it even means.

Go by Google searches, on the other hand, and there were more people hitting the keyboard looking for a fact check than wondering about post-truth anything. The same thing happened last time the U.S. had a presidential election.

Post-fact and post-truth: I think they could both end up bookends on a shelf around postmodern. The phenomenon described is real, but the jargon isn’t that useful – and I agree with Alexios Mantzarlis: getting over-enthusiastic with branding things “post-truth” will itself mislead.

~~~~

The cartoons and illustrations are my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

The term “virtuous spiral of trust” was coined by philosopher Onora O’Neill in her BBC Reith Lectures.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Maybe this is part of the post-Trump despair that seems to be displaying itself on many academic blogs, but I ended up agreeing with less of this post than normal. The internet can spread misinformation, but so can academic journals and the mainstream media. The internet makes it easier to fact-check and challenge dubious claims, and easier for marginalised groups to organise and challenge the prejudices promoted about them from by authority figures.

I’m surprised that concern about ‘post-truth’ getting so much attention now, and this has been a reminder of how different classes of people can see society in such different ways. Many of us have been trapped in a ‘post-truth’ world for some time, partly because of trust in ‘science’. Problems with hyped and misleading research have been having a serious impact upon patients lives for decades. In the UK, the government founded it’s approach to disability benefits on biopsychosocial quackery, leading to poverty, suicides and a serious loss of control for those unfortunate enough to be dependent on state benefits. The UN has now condemned the UK for serious violations of the rights of disabled people[1], although it seems that the general public would prefer to ignore this and go on trusting our authority figures. Few in academia were willing to take the time to look critically at the biopsychosocial research used to justify these policies either[2].

The PACE trial, uniquely part-funded by the UK’s welfare department, has attracted some critical academic attention recently, but only after years of campaigning by patients. A patient needed to fight a complicated legal battle to gain access to data showing that, using the trial’s pre-specified recovery outcome, biopsychosocial treatments failed to improve recovery rates, despite the hyped claims made by the trial’s researchers and funders[3]. Even after this, few in academia seemed to recognise the moral importance of this scandal. Indeed, many seem more concerned about the hardships endured by the researchers who had to endure mere patients pointing out the serious flaws within their work.

Until more is done to fight against poor quality research and the harm it does to people, distrust of science is only going to grow. In terms of social capital and ‘trustworthy’ spheres of influence, the PACE trial alone undermines trust in almost the entirety of the inter-connected UK medical establishment.

The internet allows people to access medical papers, check references, and see how the sausage is made. The people being harmed by spun research pre-internet would largely be left isolated and confused, now they can connect with one another, discuss and debate their concerns, and help identify what has gone wrong. We have seen how with PACE some authority figures, including current President of the Royal College of Psychiatry Simon Wessely, have attempted to use the media to smear and undermine patients for daring to criticise the work of researchers – such an approach will no longer work at a time when patients are able to connect with one another and check the accuracy of the claims being made.

Legitimate scepticism of poor quality science may discourage blind faith in areas like global-warming and evolution, where there are powerful economic, political and religious factors that can distort people’s understanding of the evidence. That will be difficult to avoid as so many of those entrenched in positions of scientific authority prefer to try to maintain deference by downplaying how serious the problems to be found within science currently are. Growing distrust of scientific authority will have costs, but it seems to me that it may be a necessary part of incentivising the changes which are so badly needed. Those working in science need to realise that today’s low standards are not acceptable and real change is needed to make science more genuinely trustworthy.

1. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/un-report-disability-disabled-rights-violating-austerity-welfare-reform-esa-pip-a7404956.html

2. A rare exception here: http://csp.sagepub.com/content/early/2016/05/25/0261018316649120.abstract

3. http://www.thecanary.co/2016/10/02/results-really-didnt-want-see-key-mecfs-trial-data-released/

Out of the 3 points I made, Fijk, one included exactly that: the need for science to be trustworthy and for the scientific record to be corrected when it’s wrong. And there’s a large cartoon to draw attention to that point. It’s the last point, not because it’s less important, but because most people aren’t scientists, so that’s not everybody’s responsibility in quite the same way – although yes, I agree that accessibility and transparency are important so that everyone can play a part there, too.

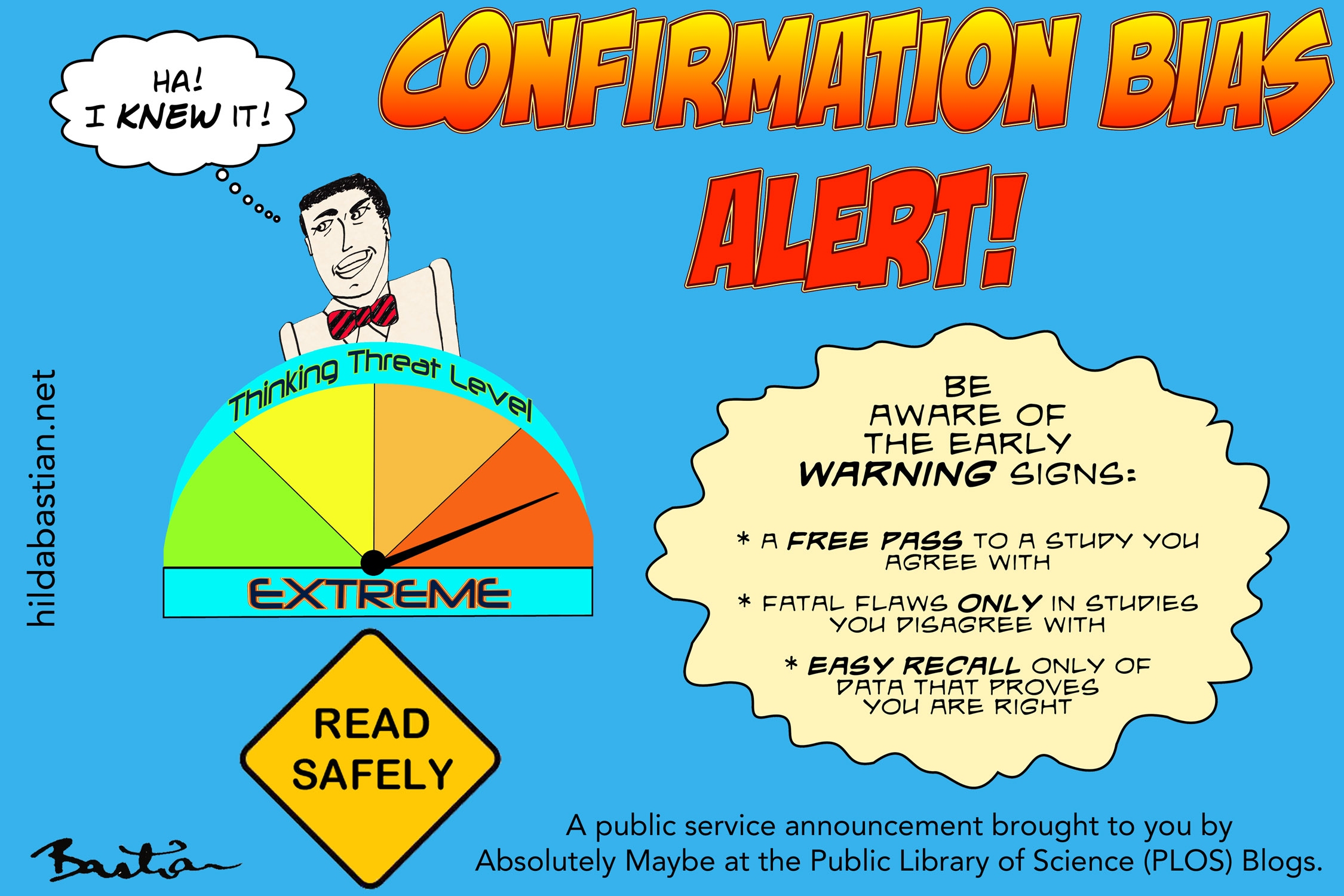

I agree that the misinformation spread over the internet often comes from academic journals and the media – and the “cartoon” on confirmation bias makes it very explicit that this is about information from academic journals, too. But that’s all part of the internet. And I agree it’s been a problem for a long time. This post is a follow-on from a previous post, so it’s not the first time I’ve addressed it. All the publicity around Oxford Dictionaries making “post-truth” its word of the year, though, inevitably gave it attention at the moment.

Unfortunately the PACE trial controversy is not unique: the problem with getting access to data and with getting corrections to the scientific record is an enormous one. I think the way you have described it illustrates the problem when there’s defensiveness instead of openness to dealing with concerns. In the end, though, the costs of dismissing science that’s right, because people don’t trust anything any more, is far higher than any benefit I can see. The colossal harm caused by a single issue – inaction on climate change because of dismissing climate science – is enough to tip the scales decisively on that one.

Yes, I am a fan of much of your work on the problems to be found within science, and that’s partly why I saw this post as a change. I may have misread you as, in the UK, I have seen the harm done by people trusting networks of scientists with ‘social capital’. I realise that you were urging caution here, but how are academics and scientists to identify who they should connect and bond with when they are being provided with misinformation by the BMJ, Lancet and the President of the Royal College of Psychiatry? I think that these sorts of personal connections have caused a lot of problems for patients, spreading prejudice and leading to people feeling they have no need to look critically at the evidence, but instead can just trust those seen as ‘a good sort’. I’d like to see greater distrust of all individuals (I say that as an anonymous patient daring to criticise Sir Simon on the internet… perhaps I just want others to be treated with the same level of instinctive distrust as myself?).

I don’t think that we can ‘balance’ the costs and benefits of distrust in science in the way you seem to suggest in the final paragraph of your response. As you say, PACE is not unique, but no-one who has been affected by issues like this, or seen how indifferent many authority figures within science are to quackery that harms outsiders, will trust the systems of science anymore. It doesn’t matter that I am concerned about the harm a rejection of the evidence about climate change will do, I still cannot defend ‘trust’ in science. So long as scandals like PACE occur, and public awareness of them grows, distrust of science will rightly spread.

The link to your past post seems to just return me to this one. On re-reading, I think that my first response may have been overly critical and missed the mark on some points, perhaps because I am a bit irritated at having spent decades of my life trapped in ‘post-truth’ quackery that serves the interest of many academics and researchers. The attention this issue has gained since Brexit and Trump showed that societies’ disinterest in the truth might inconvenience the privileged liberals (not to say that you are one) who have previously benefited from so many ‘post-truth’ myths (the misguided faith many have in scientists being a part of that) is galling. Sorry if my own frustrations with others biased my reading of your blog (although this blog still leaves me with the impression you think that things are less bad than they seem to be, at least in the UK).

These are really important points: I think you hit a critical nail on the head around being treated with disdain or distrust. It’s what I’m getting at with the cartoon of someone thinking he’s so much smarter than other people. No one can expect to be trusted by people they treat with utter disrespect. And I certainly don’t think people should be trusted just because they are scientists – or distrusted only because they are not. I don’t think I wrote it that way, either. But I certainly agree many people do approach the issues the way you’re describing: along the lines, really, of “this is how we get all of the masses to trust us just because we’re scientists”. I don’t believe anyone should trust people peddling misinformation: which is why I’m advocating slowing down to make sure what you’re circulating is solid, and that scientists have an obligation to make sure their work is trustworthy – and correct it properly when they find it’s not.

I can see why this stacks up for you this way: science hasn’t produced a lot of value for this particular condition. So there’s not much there to counter the negative. But take diabetes: there are examples of harm done by bad science – but then there’s insulin.

I think the extinction of species and consequences of rising sea levels, which could be prevented if lack of trust in climate science didn’t reduce political will to take action, is such a massive amount of harm, it does tip the scales, so I’ll make that my final paragraph again. This is the danger of throwing babies out with bathwater. Just because there’s bad science, and because scientific/technological developments have created many problems (including for the environment), that doesn’t mean disregarding solid, important science is ok.

(I corrected the link in my original reply: this is the post I meant.)

Dear Hilda,

Thanks so much for this post. I appreciate this advice on what we can do. However, I feel that we have heard it all before and this approach is not working. As a microbiologist, I have taken to heart the positive role that I can play in listening to people’s concerns about vaccines and sharing the evidence that we know supports the case for vaccinating children. However, time and again, it has been difficult to counter individual conspiracy theories, and false equivalencies whether they are presented in the media or the internet. It seems that as long as individuals feel that their beliefs are being challenged by my own beliefs, I have come to realize that I cannot erase the misinformation that forms the foundation of that person’s beliefs. This is true regardless of the level of trust between me and another individual or the level of respect and empathy that I consciously make an effort to express.

We have seen the same patterns between evidence-based policies and belief-based decisions among anti-vaxers, climate change deniers, and countless other groups during this past election.

Often it seems that the response to these is that scientists have to try harder and be better at communicating with everyone so that they can see that scientific evidence should be the basis of their beliefs. I am not convinced that there is evidence that this is effective. Please correct me if I am wrong! In my personal experience, those who are open to scientific evidence start off from a place where they don’t have deep rooted beliefs in unfounded conspiracies and do have a basic understanding of scientific principles. I am interested in learning the evidence that an army of well-intentioned scientists communicating a message can make an impact in changing attitudes towards science. I am also interested in learning of a single example of when scientific correction has helped support better public attitudes towards science.

I am a huge fan of efforts such as those at The Frameworks Institute (http://www.frameworksinstitute.org/) where linguists, anthropologists and other scientists take a research-based approach to learning how to communicate scientific truths. Unfortunately, we all don’t have the bandwidth to this at an individual level. There is also evidence that any information in social media on vaccines results in the propagation of negative conversation on the topic (http://epjdatascience.springeropen.com/articles/10.1140/epjds16). This suggests that engaging in the conversation is not necessarily a helpful thing.

Ultimately, I think I am personally tired of being blamed for not trying hard enough to be a positive ambassador for science. I am frustrated that fake news has become so abundant and lead to harmful outcomes for the public whether they be increase in unvaccinated children at school, inactive response to climate change, or a violent attack at a pizza parlour (#pizzagate). I am frustrated that our elected officials do not denounce fake enews and is divided into 2 camps, one that supports truth and one that does not. I am frustrated that truth itself is being rebranded as liberal opinions…I think what we need is something bigger than individual scientists acting in a responsible and engaged manner. I am not saying anything new, I realize. But just wanted to add to the conversation and hope that we can work together to prevent a return to the dark ages that is driven by half of the population.

Sincere regards,

Thanks, Bamini – I’m sure you speak for a lot of people. So I ended up writing a follow-up post on the issue of why I believe individual actions are worthwhile: When Science Polarizes.

I don’t know whether you’re right or not that your efforts have had no impact. If you’re expecting instant gratification, then you would likely be disappointed. In your comment, you speak about people and their beliefs in disparaging, pejorative terms. I don’t think the point of the arguments about respect suggest that feigning it works: it needs to be real. Being trusted in one area doesn’t necessarily translate to trust in another.

I re-read my post, and I can’t see why you assumed I was talking only about scientists. I make the point that the age of experts holding sway is over, and this is now a social process that’s everybody’s responsibility.

I don’t agree with you that everyone should see that “scientific evidence should be the basis of their beliefs”. Individuals make value judgments on all sorts of bases, and I don’t know that this could, or even should, change. We don’t even have sound enough scientific evidence for most decisions, and even when it’s strong, other factors often quite reasonably weigh more on a personal decision.

In addition, the quality of evidence is frequently exaggerated. I believe that’s contributed to an erosion of trust in scientists – a point made strongly by fijk, who commented on this post just before you did.

You said, “I am also interested in learning of a single example of when scientific correction has helped support better public attitudes towards science”. A single example with a mass effect? That sentence sets me up to fail, no matter what I say, I fear. But imagine where we would be now if Wakefield’s study had never been retracted by the journal? That’s an individual example of a correction with great consequences.

If scientists want to be trusted, then their science has to be trustworthy and people need to trust them. Trust is a complex construct: it’s an emotional response. It can be held individually, and by groups. (See for example the ways types of trust are defined in the social capital glossary I linked to in my post.) Why should anyone trust someone who communicates false information? There’s even less reason to trust someone who circulates false information unwittingly, and after knowing it’s false, doesn’t correct it.

I disagree that the study of Twitter data you cited is evidence that engaging in discussion per se could make it worse. There are a lot of confounders there, and very few available measures. I’d agree it could suggest that picking partisan fights in social media on vaccination adverse effects escalates, for example, but it’s not a study of moderate discussion, and its effects on readers whose views could be swayed. At some point, I’ll write a post about discussing vaccine adverse effects, because I think it’s a good example of where science partisans actually fuel exactly the partisanship they want to dispel.

I agree totally that few have the bandwith to spend learning the mindsets and skills needed for effective persuasion on a particular issue – and then have the time to carry it through. That’s intense. And I agree social and political actors have important roles to play. Even there though, pressure from individuals can count.