Black History Month: Chemists’ Powerful Stories & the Sociologist Who Studied Them

It was “a large, plain white building”, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, “on the banks of the Seine, opposite the Rue des Nations”. It housed the section on sociology at the 1900 Paris Exposition, and, the great sociologist said, you could be

…rather disappointed at the exhibit; for there is little here of the “science of society”…

In the right-hand corner, however, as one enters, is an exhibit which, more than most others in the building, is sociological in the larger sense of the term–that is, is an attempt to give, in as systematic and compact a form as possible, the history and present condition of a large group of human beings. This is the exhibit of American Negroes, planned and executed by Negroes…

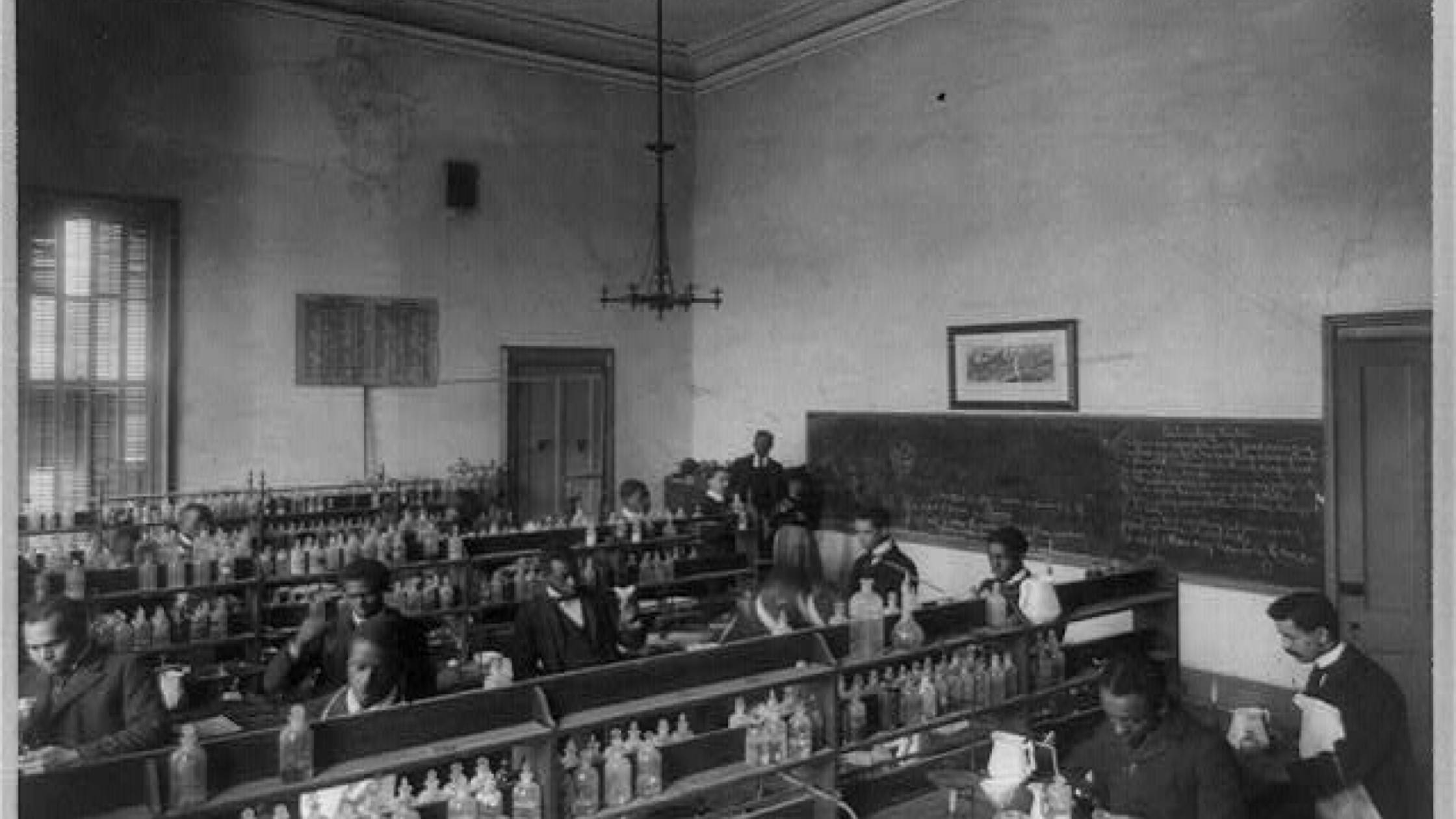

Du Bois was then Professor of Sociology at Atlanta University. And he had curated 363 of the images shown there, amid charts, maps, patents, and models of the progress of African-Americans, from enslavement to the turn of that century. This is one of the photos he chose. It’s the chemistry lab at Howard University in Washington DC:

Over a hundred years later, another sociology professor from Atlanta, Willie Pearson Jr, published a book of his national study of African-American chemists with PhDs – Beyond Small Numbers: Voices of African PhD Chemists. By then, he already had an impressive body of work under his belt. Pearson was awarded his own PhD in sociology back in 1980/1981, with the dissertation One in a hundred: a study of black American science doctorates. He has spent the decades since studying and encouraging the participation of African-Americans, women, and minorities in science. You can find out more about his work in the Wikipedia page I wrote about him this month. Here’s a photo I took of him at a workshop:

Pearson’s book on African-American chemists is a tremendously valuable resource. For one thing, it provides an overview of relevant issues and literature up to the early 1980s, especially when taken with his earlier book, Black Scientists, White Society, and Colorless Science: A Study of Universalism in American Science. And it captures a broader picture of African-American chemists than we can get from history told as a series of stories of the most well-known individuals. It’s particularly critical here, because, as Pearson points out,

Science is developed through the day-to-day activities of hundreds of hardworking and mostly little known men and women. African Americans in this group have a far lower profile than Whites. Their achievements have been underplayed, neglected, or ignored.

I’m going to tell stories of some of the prominent people’s lives here, too, but with an eye to the sociological analysis Pearson provides. First, though, let’s look at the study at the heart of the book, involving questionnaires and interviews and some context.

In 1940, there’s an estimate that out of the 70,000 chemists in industrial research laboratories, 300 were African-American, but Pearson urges caution on numbers like these: we don’t know who was able to keep their heritage hidden, for example. In the 20 years before 1998, about 20 African-Americans received doctorates in chemistry a year – less than 1% of the rate for white Americans – but the number fluctuated a lot.

Pearson interviewed 43 of 44 randomly chosen chemists with degrees prior to 1994, of whom 7 were women. The overwhelming majority were the first generation to go to university, and they were far more likely to have lived in poverty than their white peers, and their financial circumstances were often acute. He found that although they were generally positive about chemistry, the careers of most had been hindered by discrimination.

That included being taken on for study or junior positions, tokenistically, with racial barriers to career advancement. Pearson said several saw research universities as places where “they were good enough to be educated but not hired”. Meanwhile, historically black institutions were underfinanced, and people often felt they had to sacrifice their personal careers to build the educational and scientific infrastructure African-Americans needed.

Women talked about the dual disadvantages of being black and female, reporting problems with white male and female colleagues, and disparate access to mentoring and opportunities. One explained one aspect of this double blind:

Even today, black females are essentially on the bottom of the pole…When people talk about recruiting more minorities to science, they mean black males and when they say women, they mean white women.

With the provisos Pearson cautions us about knowing for sure who was first, let’s start with one.

~~

As far as we know, though, the first African-American to earn a PhD in chemistry was Saint Elmo Brady.

Brady first studied chemistry at Fisk University in Tennessee, an historically black university where he was inspired by Thomas Washington Talley. Talley’s life puts this time into historical perspective: his parents had been enslaved. Talley is fascinating too – he spent the summer of 1916 studying at Harvard, and he got his own PhD in chemistry from the University in Chicago in 1931, when he was 61. Brady took over the Chemistry Department chair from Talley when he retired, and there is a building named after the pair at the University. Brady said:

I do not remember Thomas Talley for the chemistry he taught me, but for the encouragement and inspiration he gave me to go on.

Brady earned his PhD in 1916 with a dissertation, The Divalent Oxygen Atom, from the University of Illinois:

Many years later, he told his students that when he went to graduate school, “they began with 20 whites and one other and ended, in 1916 with six whites and one other.”

Then, he faced a stark choice:

Here I was an ambitious young man, who had all of the advantages of a great university, contact with great minds, and the use of all modern equipment. Was I willing to forget these and go back to a school in the heart of Alabama where I wouldn’t even have a Bunsen burner?

Brady chose to go back to Tuskegee, Alabama. He devoted a lot of his life to building educational opportunities for black students, developing the first graduate program for African Americans in chemistry, and chemistry departments at several historically black universities.

And along the way at Tuskegee there was this: Harvard has a signed copy online of one of Brady’s 3 monographs on Household Chemistry for Girls.

~~

The year Brady got his PhD, a young man from Alabama, whose grandfather had been enslaved, started his chemistry degree a long way from home. Percy Lavon Julian was living in the attic of a fraternity house, sometimes digging ditches in the day to pay for classes he would go to at night:

On my first day in College, I remember walking in and a white fellow stuck out his hand and said, “How are you? Welcome!” I had never shaken hands with a white boy before and did not know whether I should or not. But you know, in the shake of a hand my whole life was changed, I soon learned to smile and act like I believed they all liked me, whether they wanted to or not.

After gaining his undergraduate degree, Julian taught chemistry at Fisk University, before going to Harvard to earn his master’s in 1923. It was traumatic for him when he realized he could never be a faculty member because of Harvard’s racist policies. He taught at African-American colleges until he gained a Rockefeller fellowship to undertake doctoral studies in Vienna. Arriving in economically straitened Austria in 1929 with American dollars and bucketloads of charm, brilliance, and diligence vaulted him into the local elite.

Julian returned to the US in 1931 with his PhD, to Howard University. He had to leave because of the scandal of partnering with the then-married sociologist, Anna Johnson. They would later marry, and the Julians were a powerhouse of a couple. (She features in this photo of an awesome group of African-American women in college, several of whom would be important social scientist pioneers.)

Julian landed at the university where he had been an undergrad, DePauw University in Indiana. And that’s where his career as a world-leading chemist vaulted off. His colleague and friend from Vienna, Josef Pikl, had come with him, and he said:

Percy generated ideas faster than half a dozen people could critically review and test them. He also did most of the writing, did practically all of the analytical work… Usually…we stayed up to 11–12 o’clock in the laboratory so that we heard some complaints of burning too much midnight oil!

He was making breakthroughs in chemical synthesis, publishing major papers that established him as a notable chemist, especially synthesizing physostigmine with a new method that enabled it to be used for the treatment of glaucoma. But despite this and the great reputation of his PhD students, racism still limited his opportunities. Then, the vice-President of the chemical company, Glidden, rang him and offered him a position as director of the soya products division in the company in Chicago. Many of the technicians in the company were German, and his acquisition of the language in Austria was a major asset along with his creative genius.

Julian turned the soya division into the most profitable part of the company, the first to develop lecithin granules. And then, another major breakthrough, building on his earlier work – synthesizing hormones from soy beans:

One day a worker in the plant called Julian, as chief “trouble shooter”, to counsel on what was to be done with a 100,000 gallon tank of “purified” soybean oil into which water had leaked. “The tank”, phoned the worker, “contains a mass of white solid”. Remembering his DePauw experience, Julian was there in a matter of minutes, had the whole tank centrifuged, and came out with an oily mass containing about 15% of mixed soya sterols.

Out of this, Julian developed a method for synthesizing first the hormone progesterone, and then other hormones in marketable quantities. In 1948, when cortisone, another steroid, was reported, he jumped onto that too, again developing methods for synthesizing it in marketable quantity. In 1953, he left the company to form his own.

By the end of his career, he had applied for about 100 patents, and had a cartload of honorary degrees and honors. Pearson wrote that Julian “change[d] the course of employment for African American PhD chemists”.

The Julians were major social activists, too. Talking about the problems facing the African-American community, he said:

I’ve been as angry as anyone else. But most people define the end of anger as when you become well-off.

That wasn’t enough to him, sociopolitically. And it wasn’t in his own life either. Here’s a paragraph from the Wikipedia page I wrote about Anna Johnson Julian:

In 1950, the couple bought a 15-room house in the upscale, white neighborhood Oak Park, Chicago, a community that “Ernest Hemingway, a native son, once referred to as the village of ‘broad lawns and narrow minds’.”[21] The couple and their children faced a sustained, violent campaign to stop them from living there. She later said: “We were pioneers facing the wilderness…only for us, it was a human wilderness – growing from bigotry.”[22] The town at first refused to switch the water on to the home, and the couple received threats.[21] At the end of November, while the house and grounds were being prepared, someone doused the inside with gasoline and then threw a fire bomb inside, which exploded but fortunately failed to ignite the fumes.[23] The house was placed under guard, but there was another bombing attempt the next June. While the Julian children were at home, dynamite was thrown from a car, but falling short of the house.[24] The couple refused to be intimidated. Percy Julian said, “The right of a people to live where they want to, without fear, is more important than science.”[10]

~~

The first African-American woman to earn her PhD in chemistry didn’t know she was the first. She was Marie Maynard Daly, born in Queens, New York in 1921. Here she is in her Queens College yearbook, when she graduated with her chemistry degree magna cum laude in 1942:

Her father, Ivan Daley, had come from the Caribbean. He wanted to study chemistry but had to drop out of Cornell University for financial reasons. She said,

My father wanted to become a scientist but there weren’t opportunities for him as a Black man at that time.

Daly would later establish a fellowship in his name for students from minorities at Queens College. Her mother, Helen, was an avid reader and encouraged her interest in books about science and scientists. Daly said:

My parents didn’t discourage me because I was a woman… I knew I was a good student.

Daly had benefited from fellowships to support her master’s, while working as a lab assistant (from New York University), finishing her master’s in a year. She gained her PhD from Columbia University in 1947. She pursued doctoral studies, she said, because during the war especially “there wasn’t any opportunity for me if I left school at that time”.

Although Daly had to face the dual hurdles society placed for her race and gender, she also gained the support of a female mentor at Columbia, Mary L. Caldwell. Caldwell was the only senior female in the chemistry department.

Daly’s career progressed steadily through medical research, studying molecular biology and then contributors to cancer and heart disease. She was a member of the New York Academy of Sciences and joined its Board of Governors in the ’70s.

In the 1970s, too, Daly took up the study of creatine – a substance that had featured in another woman’s story that we’ll get to soon. For our next story, though, we go back to Georgia.

~~

“Chemistry ruined me; it turned me around”, Hosea Williams said in an interview in 1968. Born in Georgia in 1926, Williams left school at 14, and narrowly escaped being lynched as a teenager. He was severely injured in World War II, spending a year in hospital, only to be back in hospital for another long stay on his return to the US, after white men beat him when he drank from a “whites only” water fountain.

With the support of the G.I. Bill, Williams went on to earn his high school diploma, a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1951, and then a master’s in Atlanta. He worked as an analytical chemist with the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) in Savannah for 11 years (1952 to 1963), in its Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine chemistry laboratory. Working on insecticide analysis, he developed a method of pyrethrin determinations. “I was a very, very good chemist”, he said in 1970. From that 1968 interview:

“I’ll never forget how a white man who had less experience and seniority than I was hired from a meat and packing company and given the job of assistant section chief,” Mr. Williams says.

“During those days, I immersed myself in my duties in the laboratory, working 12 to 14 hours a day to become an excellent chemist. Later on in my career I realized that I was being used for window dressing – to lead visiting officials to believe that the place was really integrated. When I did complain of the injustices there, I was nearly forced out of my job.”

That was in 1963. From his 2000 obituary in the New York Times:

Mr. Williams said he hit a racial ceiling at work; and about the same time, he was beginning to feel guilt and then outrage about the acquiescence of black people like himself. He took to dashing off during his half-hour lunch break to deliver speeches in a downtown park, sometimes still wearing his white lab coat. Eventually, he was arrested and jailed. When he got out, he took a year’s leave of absence from the Agriculture Department to do civil rights work. He never went back.

Here he is talking to marchers in Alabama in 1965:

He had already been active in civil rights organizations for several years, since a time he took his sons to a drugstore and had to tell them they couldn’t have a coke at the soda fountain because it was segregated.

Williams’ motto was “unbought and unbossed”. He had troubled times later in his life, but he played a crucial role in the movement in the ’60s. He was regarded as Martin Luther King Jr’s field general: King “affectionately called him ‘my wild man, my Castro,’ in recognition of Williams’ skills as a protest organizer”, and personally raised the funds to employ him.

Williams campaigned on voter registration, segregation, poverty, and workers’ rights, and was arrested more than 100 times. In 1965, he co-led the first Selma to Montgomery march with John Lewis, a turning point for civil rights called “Bloody Sunday” after state troopers brutally beat so many peaceful demonstrators. (He was played by Wendell Pierce in the movie Selma – the one who said “May I have a word?”, at 1.41 minutes in the movie’s trailer.)

Williams was there at the motel in Memphis, too, when Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968. He is the one on the far left in the famous haunting photo on the balcony the day before.

~~

In 1963, when Williams left the USDA, Alma Levant Hayden became a branch chief in the Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry at the FDA. She is the first African-American scientists known to work at the FDA, and she came there with a master’s in chemistry from Howard University, after working at the NIH in the 1950s. So she may have been the first African-American woman to be a scientist at a national science agency in the US. Here she is at an NIH lab, spraying chromatogram with reagent:

Hayden originally wanted to be a nurse, she told a 1962 “Success story panel” at Howard University, but became so interested in chemistry she “just didn’t want to part from it”. She urged the young women there to

Always try to do the very best, and to be the very best, in whatever group you are working with.

Hayden clearly practised that. The FDA back then didn’t want to promote African-Americans, because senior people might have to testify in court, and they were concerned how that would play out in racist parts of the country. A classic Catch-22 of racial discrimination. But they promoted Hayden. And it wasn’t long before she was indeed testifying in court.

It was about the investigation of a claimed cancer cure, Krebiozen. The manufacturers had been persuaded to part with an ampule of the stuff for FDA testing. Here’s what happened next:

On Sept. 3, 1963, in the laboratory of the FDA’s Spectrophotometric Unit, not far from the Mall, Hayden opened the sealed vial in the presence of other experts assembled by the government. The proceedings had the air of a trial, and, indeed, the battle over Krebiozen was to land many of the principal players in court for years.

Hayden carefully removed a microgram portion of the substance inside and mixed it with a potassium bromide solution. She placed this in an infrared spectrometer, a device that uses infrared light to trace a chemical fingerprint of a compound.

With the trace made, Hayden compared it with known chemicals until she found a match. The result? Krebiozen was creatine, which the FDA described as “an amino acid derivative plentifully available from meat in the ordinary diet.” Creatine is a normal constituent of the human body, readily — and cheaply — available anywhere laboratory chemicals are sold.

It was not a cure for cancer, and Krebiozen could not be marketed as such.

She had been looking for a match among images of 20,000 known substances, arranged alphabetically, so creatine starting with a “C” was a giant timesaver!

A few years later, cancer ended Hayden’s life horribly early: she was only 40.

~~

Meanwhile, also in 1963, Samuel Proctor Massie was elected President of North Carolina College in Durham. He would go on to become the first African-American professor at the US Naval Academy, and in 1998, was one of the 3 African-American chemists named by C&E News as one of the top 75 most distinguished contributors to chemistry. (The other 2 were Percy Julian and George Washington Carver.) ANd he’s getting the last word in this story.

Here he is at a lab at the Naval Academy:

Massie was born in 1919 in Arkansas, and was eventually awarded an honorary doctorate from the university there that rejected him because of his race. He graduated from high school at 13 (!) after following his schoolteacher mother from class to class. Massie had his chemistry degree summa cum laude by 18. He then enrolled for doctoral studies at Iowa State, but wasn’t allowed to live on campus or work in labs with white students:

The laboratory for the white boys was on the second floor next to the library. My laboratory was in the basement next to the rats. Separate but equal.

His studies were interrupted by World War II: he ended up working on converting uranium isotopes for the Manhattan Project, and radiation left him with keloid scars on his back. Massie became a chemist in hopes he could help his father, who had asthma, but Samuel Massie Sr died of an asthma attack during the war.

Massie would go on to work that contributed to the development of therapeutic drugs, with a paper he wrote summing up his lab’s work on phenothiazine regarded as a classic – he had 500 requests for reprints of that 1954 article. He also worked on foams to protect against nerve gases, and chemicals to prevent barnacles attaching to ship hulls. And Massie spent years supporting the development of educational opportunities for African-Americans and other minority populations. The Department of Energy endowed a series of chairs in his name. He said of teaching at the Naval Academy:

“Scholarship is emphasized here — you knew you could expect certain things of your students”, he said. “You had enough money to have the proper equipment, and students could afford all their books”, unlike students at some of the civilian colleges where he taught.Massie said midshipmen were sometimes baffled by his unorthodox way of scoring exams – two points for each question they got right, but 50 points subtracted for each one they got wrong. He was trying to prove a point to them: “Everything in life doesn’t have the same value”, he said. “It depends on the circumstances.”

~~~~

In 1977, African-American biochemist Gladys Williams Royal mounted a race discrimination lawsuit against the Department of Agriculture. If you have access to information about its resolution, could you please add it to her Wikipedia page? (Or let me know via the comment section below or on Twitter. If you don’t want me to publish the comment, just let me know that.)

If you want to read another inspiring chemist’s story with an amazing collection of photos, check out Burning Ambition, about Reatha Clark King.

And for amazing chemist’s life connections, check out the first woman president of NOBCChE, Winifred Burks-Houck from Alabama, reportedly the great, great, great granddaughter of Harriet Tubman.

To jump to today, you can start by following NOBBChE and Raychelle Burks, @DrRubidium, on Twitter, who describes herself as a “Chemistry Blackademic in the Ivory Tower”.

I keep mentioning Wikipedia pages I wrote, to send a signal that there is still so much to do there. This month, when I checked out Samuel P. Massie, his page was just a paragraph that didn’t even begin to do him justice – so much so that he was rated as of low importance by Wikipedia editors. Interested? Check out my post on Wikipedia activism and diversity.

See also:

Black History Month: Mathematicians’ Powerful Stories

All this blog’s posts for Black History Month

The blackboard image here is my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). It pays homage to mathematician and educator William Schieffelin Claytor, based on work he published in 1937 in the Annals of Mathematics, “Peanian continua not embeddable in a spherical surface”.

Other image sources (alphabetical order by surname of subject):

Photo of Saint Elmo Brady, via BlackPast.org (public domain).

Photo of Marie Maynard Daly in 1947, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Alma Levant Hayden was taken at the NIH in 1952, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Howard University’s chemistry lab around 1900, displayed as part of the American Negro exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900, via Library of Congress (classified as no known restrictions on publication).

Photo of bust of Percy Julian by Brian Crawford on Flickr (CC-BY-2.0). Artist who sculpted the bust not known. It’s in Scoville Park, in the area Julian lived, Oak Park, Illinois.

Photo of Samuel P. Massie, at the US Naval Academy, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Willie Pearson Jr is one I took at a workshop in Washington DC in 2017, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Hosea Williams is by Bob Fitch, and comes via an archive of his social movement photos at Stanford (reproduction allowed for non-profit organizations).