Open Access 2014: A Year that Data Cracked Through Secrecy and Myth

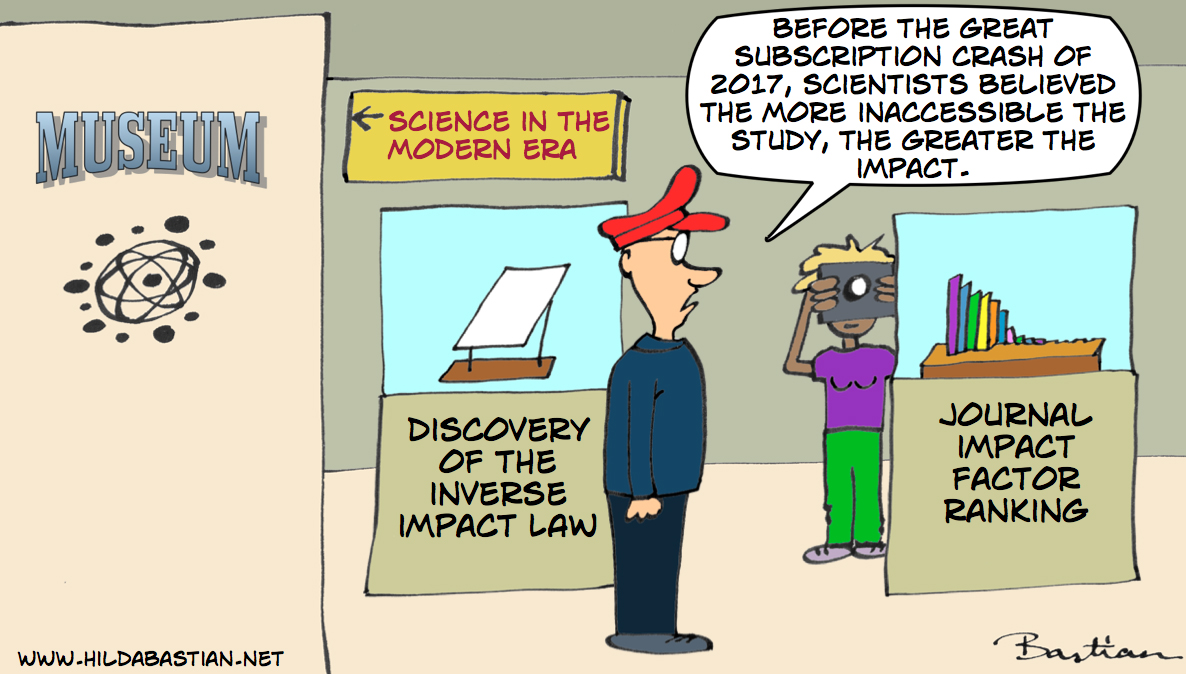

Scientists created a rod for their backs when they allowed the journals in which their work is published to become the arbiters of its scientific merit.

A small tier of journals locked behind expensive paywalls became the elite of the elite, rejecting almost all the manuscripts received. That sends scientists on a time-consuming cascade of submission and re-submission to multiple journals. It delays access to research results and discussion for many months – and costs other scientists millions of hours of often-redundant review time.

This editorial peer review hasn’t been shown to reliably improve quality – and high impact factor journals, inevitably, fail to ensure quality.

What’s more, by not publishing open access, scientists lose out on the very things they really want: to be read, to be cited by other scientists, and to have access to as much funding as possible. The cost of scientific publishing keeps draining resources:

“It turns out that scholarly publishing does not operate like a classic market. For a number of reasons, no effective mechanisms for restraining prices have emerged.”

Last year I wrote that critical mass in favor of open access had been reached among research funders. That continued to grow in 2014. Financial pressure grew on both authors and funders, too, as more research attracted article processing charges (APCs).

Commercial non-disclosure agreements around journal subscriptions took a hammering. The year’s drama started in December 2013, when France’s national negotiators for university subscriptions balked at Elsevier’s asking price for its publications…

January: The year’s first surprise – the University of Montreal did not to pay for Wiley journals in 2014. A second Canadian university, Brock, followed suit for 2015.

February: France negotiated a deal with Elsevier after all (an unconfirmed report estimated it at over $40 million annually for 5 years). But there was at least a small flurry of cancellations and tense negotiations elsewhere.

March: The Wellcome Trust (WT) reported that the average APC was now $1,418. Subscription journals with APCs for open access (“hybrid” journals) were more, and increasingly, expensive than fully open journals. WT released full data on what they spent on APCs, encouraging support for fully open access journals – and funders to apply pressure on the market.

The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) announced that only open access work published from April 2016 would be eligible output for the Research Excellence Framework (REF) that determines university funding. (Full policy and FAQs came later.)

April: Patrick Dunleavy proposed modernizing citation:

“With open access spreading now we can all do better, far better, if we follow one dominant principle. Referencing should connect readers as far as possible to open access sources, and scholars should in all cases and in every possible way treat the open access versions of texts as the primary source.”

Tim Gowers reported on subscription cancellations and expenditures around the world.

May: Mexico passed open access legislation. JISC announced a reduced subscription deal for UK institutions with Sage (followed by Wiley and Taylor & Francis later in the year). And new data showed the fully open access, non-subscription journals kept booming.

June: The next big reveal came from the United States. Data on what US universities are paying for their subscription deals were dug out by economists (with some legal action). Similar sized universities paid Elsevier from $1.2 million to $2.2 million for exactly the same bundles. Similar universities paid double others for Wiley journals too.

And in Sweden, another study showed that open access articles in a repository get more citations than articles behind those expensive paywalls.

July: Nature Communications was the next journal to suggest an open access citation advantage. And PeerJ, the innovative fully open access journal with a preprint server and modestly-priced lifetime publishing plan, published its 500th article. Harvard reported that its repository had passed 3.4 million downloads.

The World Health Organization joined the UNESCO in the UN open access ranks, and Denmark released its national strategy to go fully open access by 2021. A roundup from later in the year shows the clean sweep of open access across the Nordic countries after Finland’s September announcement of plans to achieve access by 2017.

August: More data from North America: this time university library budgets. And the Eigenfactor plot of cost-effectiveness of open access at individual journals got attention. (An article followed.)

September: It felt like a symbol of the times: the SWETS subscription service for libraries declared bankruptcy. More on the background – and the scramble to cover 2015 subscription losses.

Institutional reports on the costs of compliance with the Research Council of the UK’s (RCUK) open access policy began appearing. A consultancy report came later, as well as parliamentary criticism.

October: More data (and modeling) from 23 UK institutions for 2007-2014 again underscored the high cost of open access in subscription journals with double-dipping for subscriptions: “The evidence suggests that price is discouraging uptake of the hybrid option.”

Another UK reveal, this time from JISC: APCs ranged from about $130 to more than $7,700 (both of those from Elsevier). The HEFCE reported that while 80-96% of articles could have free-to-read copies deposited by authors at their institutions, only an estimated 12% of authors actually do it.

California passed open access legislation (read about the background here). The University of California announced it would launch open access journals in 2015.

PLOS Medicine celebrated its 10th birthday (a post from me on the celebrations). The European Commission estimated that with embargoes expired, more than half of the articles published between 2007 and 2012 are now free to read.

And the rise in retractions at Nature added to the data questioning the assumption that high impact journals can ensure quality.

November: More reveals: Michelle Brook gathered data for UK institutions via Freedom of Information requests, and Stuart Lawson and Ben Meghreblian did too (5 years’ worth). Heinz Pampel added German APC data to the year’s flood as well.

For a while, it looked as though the Netherlands might become the first country to cancel all Elsevier subscriptions, when negotiations broke down. Elsevier is back at the negotiating table, though – and Springer reached an agreement.

The Swiss national court dismissed legal action brought by Elsevier, Springer, and Georg Thieme publishing companies against the Zürich library’s document delivery service. The library’s mandate to support science, the court ruled, superseded the companies’ commercial interests. The library can now send copies and scans of articles anywhere in Switzerland.

And the National Institutes of Health (NIH) extended reporting mandates for clinical trials.

Hundreds of early career researchers and students from around the world gathered in Washington DC for the exciting inspiring first OpenCon. (See my post and the keynote presentations). Meredith Niles, received an inaugural leadership award. She spoke about her reaction to finding out a publisher could stop her sharing her research:

“I can’t believe this is the system we have accepted.”

December: The Netherlands released its plan to achieve 100% open access for the nation’s academic output by 2024. India’s Ministry of Science and Technology released an open access policy. And the Gates Foundation raised the bar for all funder open access policies: open access and open data from 2015 – and no embargo period at all from 2017.

December included two other landmarks that help give us historical perspective. ArXiv, the groundbreaking preprint initiative that begin in 1991 with physics, will soon clock past the 1 million submission mark. And the Open Library of Humanities is cranking up.

One represents how strongly open access has taken hold in a forerunner – “how a community stopped worrying about journals and learned to love repositories.” The other, its continuing spread.

While many believe that much further fundamental change in science publishing isn’t likely, I’m inclined to agree with Pete Binfield’s assessment of open access at OpenCon: “It’s on a sort of unstoppable roll.”

~~~~

Open Access 2015: A Year that Access Negotiators Edged Closer to the Brink

Open Access 2013: A Year of Gaining Momentum

Updates since original posting: Additional information and links on the California open access legislation thanks to Benjamin Schwessinger and Lenny Teytelman. And I added a personal highlight of the year for me to October: PLOS Medicine‘s 10th birthday.

Interest declaration: I’m an academic editor of an open access journal, PLOS Medicine.

More posts from me on open access

The cartoon in this post is my own (CC-NC license): more at Statistically Funny.

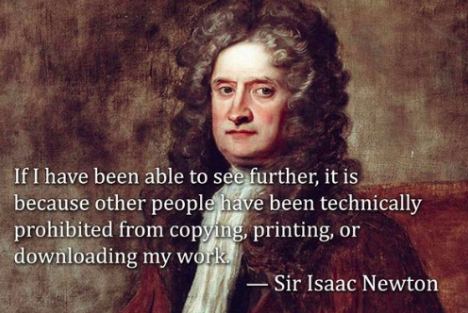

The Isaac Newton meme is by 5 Useful Articles, “IP updates with a modicum of humor” by Parker Higgins and Sarah Jeong (Follow on Twitter.)

I took the photo of Meredith Niles at OpenCon 2014 (CC-BY license).

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.