8 PubMed Ninja Skills

A few million people use PubMed every day – many pretty much every day. And everyone’s got their own habits, shortcuts, and functions they rely on. Before I get to my personal top 9, though, a quick tour of the PubMed universe.

PubMed will be 20 years old in a few weeks! It’s run by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) – part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

PubMed has over 25 million citations of biomedical literature. More than a million are added each year now. There are 4 sources:

- MEDLINE journals (journals with primarily biomedical content that meet NLM criteria);

- Some full-text electronic journals in PMC (PubMed Central);

- Full-text books and documents in the NLM Literature Archive (Bookshelf);

- Manuscripts of journal articles submitted by authors under funders’ public access policies.

Mostly, MEDLINE journals will only have citations and abstracts, usually with a link to the full-text at the publisher – but some also deposit full texts in PMC.

The other 3 sources are all full texts. You’ll see links to those full texts from PubMed, either to PMC, the Bookshelf, or PubMed Health (PubMed’s clinical effectiveness resource).

The author-submitted manuscripts can come from MEDLINE or PMC journals, but not only. They are there because the funders of the research require articles to be deposited in PMC. Some of these are European research funders through Europe PMC, but most come from the NIH and other U.S. agencies. (More U.S. agencies, like NASA, are joining soon.)

Because there’s so much in there now, I think the most critical skill is how to avoid being swamped with things that don’t help. Let’s get started!

1. Precision searching

You might want to cast the net as wide as possible. PubMed’s default will often help you do that by automatically extending the search. Way down on the right you’ll see a section called Search Details – that shows you the detail of the search it’s running. That can be extremely helpful. For example, searching for adolescent will expand into this MeSH term (medical subject heading), scooping up the plural and variations like teenager.

But it’s not always helpful, especially if you want to search for something exactly – especially a phrase. You can make it search specifically for what you want by using quotation marks around your search. (That works on other search engines too, like Google.) That won’t always make a big difference, but it can. Here’s an example where it makes a lot of difference:

Another way to make your search more precise is to use an option available via Sort by Most Recent (above on the right). The second option there, Relevance, changes from the default of latest addition to PubMed, to ordering the results with the most relevant first.

And then there is Advanced search (the blue link just under the search box above). That lets you search in particular parts of records, like authors.

2. Faceted searching

You can refine your search using filters. There are a group of popular ones listed down the sidebar on the left – like review and publication dates. When you click on one, your results will narrow down to just the type you’ve chosen.

Some tips: free full text will show all the ones that are free in-house at PubMed – but it can’t always detect whether or not the article is free at the publisher website. That depends on the publishers providing the data and keeping it up-to-date – it’s a bit variable. And it’s easy to forget to un-click filters – so keep an eye out for a reminder message like this on later searches:

![]()

3. Building searches using AND, OR, NOT, and parentheses

Using the words AND, OR, and NOT in full uppercase turns them into commands in a PubMed search. They’re called Boolean operators. It’s like building a mathematical formula. Parentheses form groups when your search string gets more complicated. For example:

(literacy OR numeracy) AND (child OR adolescent)

4. Following the Similar Articles trail

This is a popular feature, and something in there has caught your eye for sure some time. When you see a record that is what you’re interested in (or very close to it), click on its abstract page. The Similar Articles section is to the right of the abstract. (The name of this feature recently changed from “related” to “similar” articles.)

Using Similar Articles is both quick and pretty thorough. It can be a massive timesaver.

5. Finding a specific citation, journal, or author

PubMed is pretty good at finding a citation when you just plonk it into the search field, but in between inaccuracies and formatting, it doesn’t always work. There’s a citation matcher to structure the search carefully – or advanced search is another way.

If you want to search by a particular journal, getting the abbreviation right helps a lot, especially if there’s more than one journal with a similar name. You can find out that and a lot more about a journal by clicking on the link on its name when you’re in the abstract view. You’ll see this:

Click on Search in PubMed to get the right search term for that specific journal. Search in NLM Catalog gets you details about the journal – including a link to their website.

For authors, using surname and initial(s) is the standard (e.g. bastian h). In the abstract, the link on an author’s name goes to other articles that seem to be by the same person.

6. Getting email alerts

You can get email alerts for new additions on any search you do in PubMed – a subject, a whole search string, a filter, a journal, an author….anything.

Just do the search, and you’ll see a blue link Create alert right under the search box. You need a My NCBI account to do this, so PubMed knows your email address. It’s free, and won’t send you any emails you don’t ask for. (You can unsubscribe to your alert directly from an email too.)

You can ask to get your alerts every day, week, or month. Be sure to specify that – the default is monthly, so you won’t get an alert for weeks if you don’t.

7. Keeping track of articles and collections and sharing them

These options on the abstract page don’t look like much, but there’s a lot of useful stuff behind them:

Send to gets you options for sharing the abstract by email, adding it to a temporary Clipboard, and more. Add to Favorites is a shortcut to managing collections of articles – or you can just save them as generic “favorites”. You can keep your collections private, or you can make them public. If you choose the public option, PubMed will give you a link that will convert to the list of articles you saved in that collection. Here’s an example – the collection link for that is: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/myncbi/hilda.bastian.1/collections/49170937/public/

You can make a bibliography of your own articles, too – private or public.

The Send to options also work for entire searches, not just on the abstract page, but Favorites is for articles.

8. Customizing your PubMed

You need a My NCBI account for this, too. When you’re signed in, up on the right you’ll see a link to NCBI Site Preferences. You change several PubMed default settings there.

If there’s a filter you use a lot, you can add it here. You can customize your own filters too. It won’t show up in the filter choices on the left: it will display the results at the top on the right every time you search.

Here’s a demo. It’s to show which records have a data link recorded for Dryad or Figshare. You find those down in the Secondary Source ID section below the abstract. There’s not many of these yet, but here’s the search string to enter if you’re interested in trying it out: Dryad[Secondary Source ID] OR Figshare[Secondary Source ID]

That’s it for my favorites! If you want to learn more or get help with searches and you’ve got access to a medical library, a medical librarian/information specialist is the real PubMed Ninja. One last tip: every PubMed page has a link to Help documentation at the top right, and to a contact form for emailing PubMed’s Help Desk down on the bottom right.

Happy searching!

~~~~

Want to learn more about using PubMed and My NCBI? NCBI has a YouTube channel with tutorials.

Disclosure: When I wrote this post, I worked on PubMed-related projects, including the now-defunct PubMed Commons. This post used to have 9 skills, the 9th being formatting in PubMed Commons. [Updated on 27 September 2019.]

The cartoons in this post are my own (CC-NC license). (More at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

PubMed turns 20 in a few weeks! You can read a bit about its prehistory here and a short overview of its first 10 years here.

Developments on PubMed are reported in the NLM Technical Bulletin.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Thank you so much. Very helpful.

You’re welcome, Islam – glad you found it helpful.

What on earth would we do without PubMed? Hope the biomedical and clinical research communities never take it for granted! Happy 20th (and thanks for the search tips)!

Thanks, Jim! It was awful before PubMed – I don’t know how we coped!

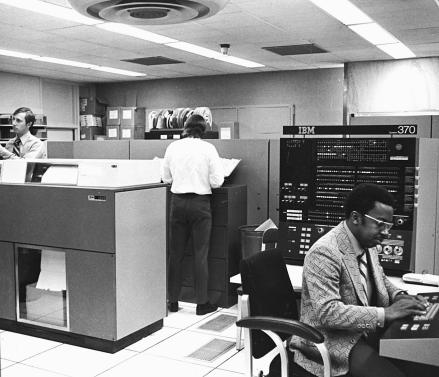

Before PubMed we coped with Index Medicus or having a medical librarian run a search. IM was so tedious, doing searches by looking under several medical subject headings (MeSH terms) for each year. You’d look in IM under all the terms of interest for one year and then start all over for the IM volume for the next year, and so on. You’d jot down all the references of interest and then go to the library stacks, pull each issue of each journal, and read the abstract. (The good news was you might find something else of interest that you hadn’t counted on, but that was scant consolation). Or you could have the librarian run a computer search for you, producing page after page of fanfold print-outs, generally with an old dot matrix ribbon producing faint type. At least those results would have the abstracts with them. It was all a time-consuming nightmare. Then along came Grateful Med, the front end program for accessing PubMed. You got charged for the searches, but it was pretty cheap. And then Congress decided that PubMed was such a valuable resource that it made PubMed free (to the whole world). I interviewed a Czech scientist in the early 1990’s and asked him how they would revitalize Czech science after more than 40 years of Communism and no access to Western journals. “We just use your National Library of Medicine online,” he replied.

Thanks! It was tough, wasn’t it? (But it wasn’t Congress that decided PubMed should be free – it was NCBI.)

Excellent and helpful. Thank you.

What I would like to know is why Pubmed indexes 30-odd journals of quackery. They are “peer-reviewed” by other quacks and are very rarely reliable. It isn’t good that Pubmed faclitates the spreading of magic-based medicine.

I’m glad it was helpful, David. I’m not from the parts of the organization that deal with the approving journals for PubMed. The email address for feedback about that is at the end of this page.