This is How Research Gender-Bias Bias Works

But how can you tell? She wanted to know why I said some work on gender bias was obviously too biased to be reliable. Bamini Jayabalasingham and I had been discussing gender issues in science, and she was interested in a systematic reviewer’s perspective on bias. She sent me a paper to look at.

Well, dear reader, I looked at it. And then I looked at it some more. Now, 2 months later, I have emerged from this rabbit hole to report what I found. This is part 1. It’s a primer for looking at a study on gender bias.

There are lots of guidelines to help you critique the reports of particular study types – the wonderful EQUATOR Network keeps a library of them. Included are the SAGER guidelines for sex and gender equity in research. This post is a guide to what to look for in a study about gender bias and women scientists.

I’ll draw a lot on this particular paper I’ve been analyzing. It’s an influential paper by Stephen Ceci and Wendy Williams in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (PNAS) in 2011, called “Understanding current causes of women’s underrepresentation in science”. It’s a review that claims there is strong evidence that there’s a level playing field for women in science. I wish that were true. I hope to see something at least close to that in my lifetime. But no, this paper doesn’t prove we’ve already arrived.

1. Who are “women scientists”?

There are 3 things to look for here. The first is, what do they mean when they say “women”? We share a gender, but that doesn’t mean we’re all in the same boat. Look at the world of difference, for example, in my post about 2 amazing women scientists in the 1920s: one’s an upper crust Englishwoman and the other is an African-American woman who had nothing like a head start. An average improvement for “women” isn’t necessarily the same as improvement for all women – and certainly not women in all countries.

As we moved in larger numbers into science over the last few decades, we brought all sorts of issues with us. You can analyze gender separately, but if you think about “women”, that’s multi-layered. There are many people doing work on those layers. Here’s a few of them:

- Nicole Stephens and colleagues on social class and first-generation college students (2014);

- Kimberly Griffin and colleagues on gender differences in black faculty (2013);

- Diana Bilimoria and Abigail Stewart on the academic climate in science and engineering for LGBT faculty (2009).

The Ceci and Williams paper doesn’t address disparities among women:

The second is, what do they mean by “scientist”? There are very large numbers of women in some disciplines and they’re scarce as hen’s teeth in others. One of the reports included in the Cecil and Williams review pointed out that there were still university departments with no female faculty in the US (2010).

Those disciplines with large numbers can dominate data easily and skew results. The average isn’t enough to consider. It’s not a level playing field for “science” till it’s level right across our fields.

Ceci and Williams pay a lot of attention to overall averages in recent decades. But in terms of women’s opportunity to flourish, not all disciplines are even in the same century. And then there’s the different sectors: the academy and industry, for example.

The Ceci and Williams paper doesn’t take uneven progress across science into account in their conclusions, and they only consider academic science:

The third point here is a critical data one: how did they determine gender, and how much of that data is missing?

Here’s a rather extreme example from a study cited in the paper: the author tried to assess gender by the names – among the 7 groups he was comparing, the number he couldn’t tell was between 20 and 50%. What’s more, it was he who couldn’t tell: this wasn’t a measure of how often the people who had potential to contribute to bias didn’t know [PDF]. (You can see my comments on all the relevant included studies in part 2 if you’re interested.)

But to that author’s credit, at least he reported it: I gave up trying to gather this item, because it was so rarely there. It can bias the data enormously. And only 1 study mentioned how they categorized gender for transgender scientists (their gender of identification).

The Ceci and Williams paper doesn’t take quality of the data on gender, or missing data (on this or anything else) into account:

Here’s a recent example of going to a lot of effort to get this right – it’s not from the Ceci and Williams paper. David Kaplan and Jennifer Mapes examined female doctorates in U.S. geography [PDF]:

First, we identified easily gendered names, such as Norman or Susan… Second we used the Web site www.genderchecker.com, which identified the gender of names based on the UK census and crowdsourcing. Third, we used Google’s search engine to find each of the remaining 1,000 individuals to ascertain his or her gender using images and personal pronouns. Only 1.7 percent of dissertations were unassigned after these steps.

Then they went through the same steps with all the advisors.

2. Publication and publication selection bias: hands up who’s not here?

The Ceci and Williams paper included 35 studies to come to their conclusions that “it’s a level playing field” and it’s women’s choices that lead to their underrepresentation. Some of those were reviews, and some were a few – but not all! – of the studies in those reviews. It was an odd set and we don’t know how or why they were selected for the review.

Take the level playing field they say exists at journals. There were at least 16,000 active science and technology journals in 2011. Ceci and William cited studies in 8 to 13, in 2 disciplinary areas. This is a drop in the journal ocean.

A bibliometric analysis of published studies on women in science and higher education identified 1,415 articles published between 1991 and 2012 (Dehdarirad, 2015). The gender and science database of a European Union project published in 2010 had 4,299 entries (Meulders, 2010 [PDF]). To do a good review on the questions Ceci and Williams asked, you’d have to sift through thousands of possibly eligible studies: and there are hundreds to find.

And that’s just what’s published. This is an area where even with all that paper acreage, there is a high risk of publication bias as well. Publishing that your journal, funding agency, or university has not prevented bias against women is no small matter. Especially in a country where there are laws against discrimination – which is a lot of the parts of the science world doing studies like this.

In 1 of the journal studies in this paper, the author had approached 24 journals: but only 5 agreed to participate. Gulp. And those might have been more gender-aware than usual for all we know.

How did Ceci and William do on publication and selection bias? See part 2! But in the meantime:

3. What are they measuring?

Let’s stick with journals for a minute. If you wanted to know if the playing field was level in science journals, there’s the articles, the editors, the peer reviewers, the editorial advisory boards – and all of that, needs to consider prestige.

Here’s another good example – again, more recent than the Ceci and Williams paper: Lesley Riggs and colleagues (2011). They looked at author position – first, last, in between – single gender, mixed gender, how much collaboration. Others have looked at who gets the invited editorials and so on.

The same applies to grants – they’re all not equal, not in size and not in prestige – as well as to institutions, to conferences, to networks. And where you land at each stage is not necessarily a coincidence or because of choice. Small advantages – or disadvantages – could all accumulate. As Virginia Valian writes [PDF]:

One might be tempted to dismiss concern about such imbalances as making a mountain out of a molehill. But mountains are molehills, piled one on top of the other. Small imbalances add up to disadvantage women. Success is largely the accumulation of advantage, exploiting small gains to obtain bigger ones.

Gender bias studies in the Ceci and Williams paper typically looked for signs of vertical progress – who’s tenured, who’s not – but those averages alone can still hide a lot.

There are other workplace issues, too, which are more predominantly women’s issues than men’s: for example, workplace sexual harassment, including science conferences and harassment in the field. It’s an area that’s getting more attention, especially since Kate Clancy’s 2013 survey and high profile cases.

Ceci and Williams stuck with a very narrow range of topics and outcome measures – which would be great, if you did it well, and kept your conclusions suitably modest. But for universal, global claims:

4. How are they measuring it?

There are 2 major aspects here: is what they are measuring capable of identifying bias or the lack of it? Many of these studies use extensive modeling based on data like the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Survey of Doctorate Recipients (SDR). Here’s one good introduction to some of the limits of this kind of approach, by Jerome Bentley and colleagues, in a report to the NSF [PDF].

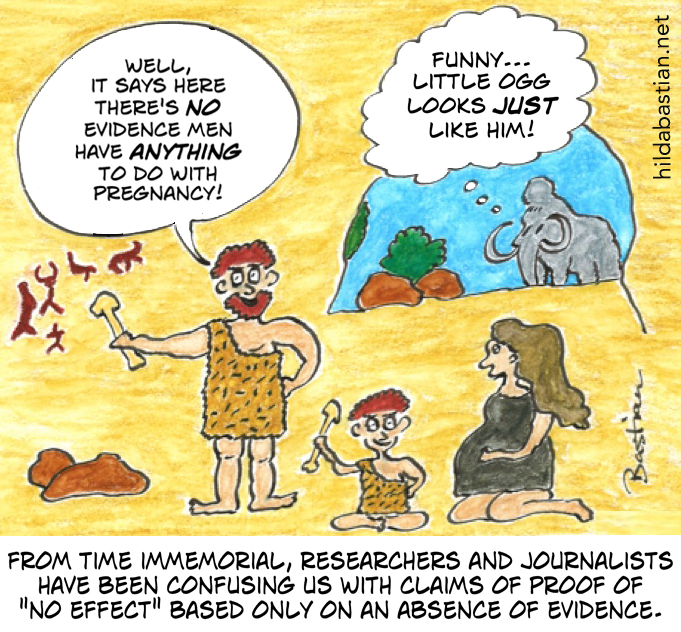

Then there are the usual questions about how you interpret the data: accounting for multiple testing when complex models are used, the trap of missing data, small numbers, mistaking lack of statistical significance for evidence of lack of effect – and over-estimating what it means when it’s there. I have an introduction to these potholes here: they apply to these studies too.

How did Ceci and Williams do on avoiding data traps and analyzing methodological and data quality?

5. Do the conclusions calibrate to the evidence?

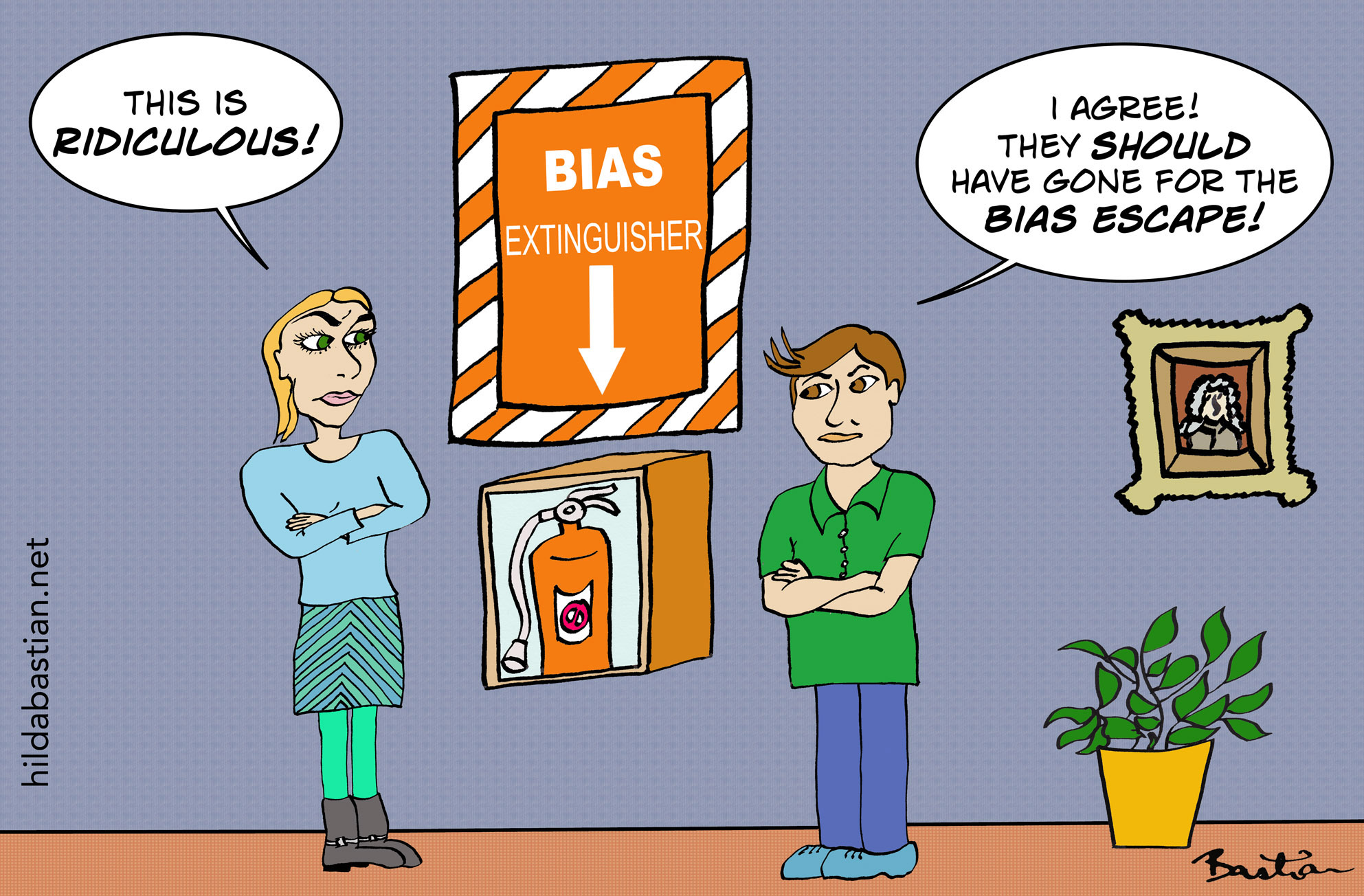

I’m going to avoid giving the Ceci and Williams paper another thumbs down here – although they get a big one, after all that, and the sweeping conclusions they land on. I’ll end with a thumbs up for something I agree with them on. A lot of research and policy on gender in science is very biased. If we allow our biases to get in the way of determining our strategies, we won’t solve our problems.

The trouble is, gender-bias bias led Ceci and Williams into the same trap, too.

[Update 6 September] My comments (including a reply from the authors) on the Ceci and Williams review, originally published at PubMed Commons (and another on a paper advancing their hypothesis about motherhood and women in science.) (And a correction: the original version said the studies on journals covered 8 to 15. It’s 8 to 13.)

Gender-Bias Bias Part 2: Unpicking Cherry-Picking

[Updates 8 March 2018] Because PubMed Commons has been discontinued, links in the above update changed. And here’s another relevant study – an example of how superficial analysis can lead us astray.

~~~~

My deep appreciation to Melissa Vaught and Bamini Jayabalasingham for the thought-provoking discussions about gender bias in science, and the research on it.

Disclaimer/disclosure: I work at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), but not in the granting or women in science policy spheres. The views I express are personal, and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIH. I am an academic editor at PLOS Medicine and on the human ethics advisory group for PLOS One. I am undertaking research in various aspects of publication ethics, but am not aware of any conflict of interest in assessing this paper.

The cartoons and photo of the NIH’s Nobel Laureate Hall are my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.