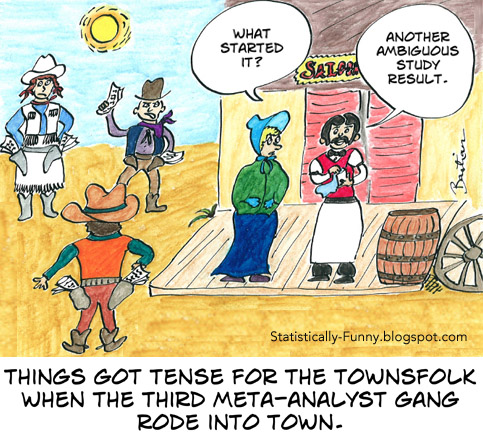

All That Meta-Analysis Backlash!

As soon as people started getting serious about systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the 1970s, the bashing started. It’s not real research! Garbage in, garbage out! You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear!

As systematic reviews became ever more embedded in health research and decision making, spreading to other fields as well, the backlash genre has thrived in their wake.

In the last few weeks I’ve been pottering away on a post of tips for gauging the value of a systematic review/meta-analysis. And so I was particularly interested in a group of these that appeared this month. The first came from Sylvie Chevret, Niall D. Ferguson, and Rinaldo Bellamo. The second, from

There was a similar core in the arguments across these pieces. So many of these studies are badly done; they often tackle questions that aren’t helpful; people doing them on the same question often come to different conclusions; and they are often misinterpreted.

Well, frankly, that sad state of affairs applies to all research types! There is no foolproof method of research. If we’re going to dump everything that gets done badly, there’ll be nothing left.

Indeed, a pillar of the backlash genre is that systematic reviews aren’t useful because the quality of the underlying evidence is so often lousy. However, systematic reviewing shines a light on that, and it is part of the solution. Critiques of bodies of literature contribute to improving standards for later research – only slowly, unfortunately. Still, having the weaknesses of a field shown in stark relief can be motivating.

There’s nothing new in the first 2 of these papers: at a certain point, if you’ve read one, you feel like you’ve read them all. The Greenhalgh paper, though, is different. It tackles the interesting question the higher status of systematic reviews relative to other kinds. The authors argue that systematic reviews shouldn’t be seen as superior, as a category:

We argue that systematic reviews and narrative reviews serve different purposes and should be viewed as complementary.

For background, if you’re interested in this, here are a couple of articles describing broad types of reviews in biomedicine, in 2009 and 2018.

I agree with some of the points – especially about emerging methods of systematic review being valuable. The central premise of the paper doesn’t really work, though, I don’t think. Although it contrasts systematic and narrative reviews, the further you go in the paper, the less apt that dichotomy is.

It’s more a depiction of a very specific type of systematic review “on a narrow question” versus a “state of the art” (the authors’ term) review by clinician/practitioner experts. Those, too, are often, they point out, “highly systematic”. Although that’s where it starts out, other types of review are progressively added, like realist reviews and syntheses of qualitative research. “The boundaries”, they write, “between systematic and narrative reviews are both fuzzy and contested”.

That’s true, for sure. But the dichotomy here isn’t systematic versus non-systematic review at all – not even in a fuzzy way. Nor is it narrative – in the sense of no quantitative meta-analysis – versus non-narrative either. At one point, I thought it was Cochrane and Campbell reviews versus everything else, but it’s not that either.

The authors note that reviews they’re calling narrative are regarded as systematic, by some at least (including me!),

However, we have had experience of journal editors rejecting reviews based on these techniques on the grounds that they were “not systematic”.

Well, journal editors make mistakes about all sorts of things. And rejecting a systematic review because it has a methodology outside a very narrow framework is definitely a big one. But advocates of different methodologies caricaturing others’ methodology isn’t going to build a bridge over this divide.

Systematic reviews are described here as finding probabilistic truth via mechanistic processes with mathematical averaging. Whereas narrative reviews achieve plausible truth via thoughtful and critically reflective processes. That’s some choice of language, and the dichotomy really doesn’t hold up.

A systematic review that “only” meta-analyzes clinical trials can also be chock-full of critical reflection, reaching very plausible conclusions. And a review that doesn’t focus on clinical trials can reach highly implausible conclusions, or deal in probabilities. Clinician/practitioners doing any kind of review can be wise – or self-serving and sloppy.

A narrative review might focus on a very narrow question. A synthesis of qualitative research is dealing with “a rigidly defined subset of the available body of work”. In fact, no review could ever possibly consider everything. (No matter what scenario I thought of, I could think of information that would escape the net, no matter how widely it was cast.)

This paper has a lot in common with studies done by really enthusiastic proponents of Cochrane systematic reviews which compare those to non-Cochrane reviews – and then include both systematic and non-systematic reviews as the comparator to Cochrane, rating quality by features hard-wired into the Cochrane software. The game is essentially rigged from the get-go. That is a shame. Because there are really important critiques to consider, all across this spectrum.

I come to this topic from an odd amalgam of perspectives and experiences, I guess, with my roots in this field springing from health consumer advocacy. And I think this statement in the Greenhalgh paper gets us to a core problem here:

Bias is an epidemiological construct, which refers to something that distorts the objective comparisons between groups.

Bias isn’t only an epidemiological construct. Sure, there is such a thing as statistical bias, and biases in design or implementation that can skew research results.

But bias can also be ideological. It can come from personal, professional or financial conflicts of interest and rivalries. Rivalries and competing ideologies are lethal to the public interest in health and social research, just as elsewhere. The alternatives to strict methodological rigor in the Greenhalgh paper rely heavily on the wisdom of authors. That’s a risky business, given our apparently limitless ability to fool ourselves, and fall into cognitive and self-interest traps.

For me, a sense of professional and ideological rivalry clouds this paper. Shaky conceptualizations and derogatory language invoke tribalistic response. That’s always satisfying to partisans, I guess. But in this case, they undermine important points about evolving approaches to systematic reviewing that could do with wider discussion.

On the other hand, one of the best critical analyses of poor use of systematic reviews also comes from Trisha Greenhalgh: her talk in 2015 at the Evidence Live conference. Highly recommended viewing!

So how do you avoid the pitfalls of unreliable systematic reviews and meta-analyses? That’s key to not throwing the baby out with the bathwater here. And that will be the subject of my next post!

To be continued…

~~~~

The cartoons are my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal.

You might be interested in a recent fascinating podcast about the use of effect size in meta-analyses in education (https://goo.gl/4yrMnF) which finishes with a discussion about the value of the systematic, narrative review element of a meta analysis.