5 Shortcuts to Keep Data on Risks in Perspective

“Risky” is definitely not a one-size-fits-all concept. It’s not just that we aren’t all at the same level of every risk. Our tolerance of risk-taking in different situations can be wildly different, too.

Our judgments about our own vulnerability and how we feel about what we might gain or lose can make a risk loom large – or seem triflingly insignificant.

We can have such a strongly fixed perspective about a particular balance of risks and benefits, that new information would have to be truly overwhelming to even make an impression. While on other issues, our perspectives can move quickly in response to incoming data.

And when it comes to risks, boy is there is a lot of incoming data! An unrelenting stream of numbers, and an explosion of visualizations and infographics, too. I don’t think this means we’re getting more objective and consistent about information and life’s choices, though.

It might even be getting harder.

We don’t have time to think and research everything through, and come to the perfect balance of knowledge for every little thing – and not even for every big thing that matters to us a lot. We need to take some cognitive shortcuts, but they leave us vulnerable to seeing what we want to see or being led astray when risks are being exaggerated or minimized. Here are my favorite 5 shortcuts to avoid the things that trip me up.

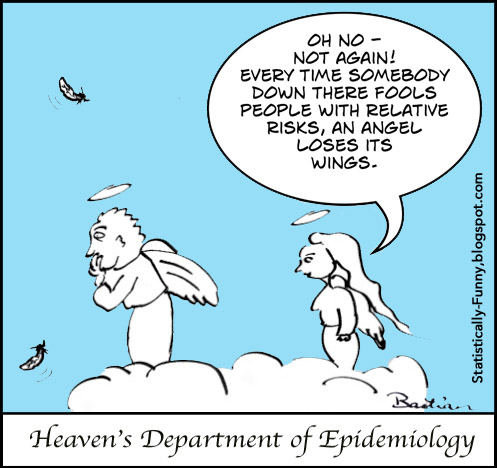

1. Watch out for risk’s magnifying glass – and cut your risk of being tripped up by 82%!

Whenever you see something tripling – or halving – a risk, take a moment before you let the fear or optimism sink in.

Relative risks are critically important statistics. They help us work out how much we might benefit (or be harmed) by something. But it all depends on knowing your own baseline risk – your risks to start with.

If my risk is tiny, then even tripling or halving it is only going to make a minuscule difference: a half of 0.01% isn’t usually a shift I’d even notice. Whereas if my risk is 20%, tripling or halving could be a very big deal. Unless you know a great deal about the risks in question – or your own baseline risk, you need more information than a relative risk to make any sense out of data. (There’s a good introduction to relative and absolute risks at Smart Health Choices.)

2. Just because one risk is “guilty,” doesn’t mean they all are.

It can be easy to jump to the conclusion that because something is “bad” in one way, then it’ll be bad on all counts. You see this happen a lot with reports of adverse effects of health care treatments. You’ll read things like, “Nausea and vomiting increased, and 8% got headaches.”

But when you look at the study in question, yes, nausea seemed to be a problem: it makes sense that it would be, and the result is statistically significant, too. (There’s more about what “statistically significant” does and doesn’t mean in this post.)

The data on headaches, though? Yes, 8% had them, that’s true enough: but it was about the same in the comparison group, too – just because 8% had headaches, it doesn’t mean the treatment causes headaches.

The same thing happens when context isn’t revealed in other circumstances. Someone says, “people who do X have a 2% risk of dying in the next 10 years.” When a 2% chance of dying in the next 10 years might be completely normal for that group of people, whether or not they do X.

3. Keep a sharp eye out for double standards on risks and benefits.

Once someone is convinced about something – including scientists reporting on their research – one of the hardest-to-resist spin techniques for them is to over-emphasize the upside (or the downside, if they’re opposed to something).

There are lots of ways to frame things so that one side seems smaller than the other. So watch out for any lopsided treatment. Relative risks used only for benefits not harms, for example.

The language could shift, too, with adjectives like “important” versus “trivial” masking things that you might think are anything but if you saw the numbers and full descriptions.

Perhaps the most common one of all, though – and it’s amazing how often we don’t even notice it happened – is when risks of harm are simply not even mentioned. That’s taking the philosophy of “Accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative” just a little too far! (More an adverse effects here.)

4. Read the fine print when there’s data shape-shifting…slowly.

We skim and scan a lot, and this makes us particularly vulnerable to getting a false impression. This can happen really quickly when we absorb the impact of a graph without reading its fine print. Or when some of the measures in text come in percentages, and other numbers are per 1000, 10000, or 100000.

Most of us need to be careful to get things into proportion when risk communications jump from “1 in 7” to “3 out of 8” and so on, too. The people writing are trying to make numbers easier to digest for people – but that can backfire.

The best thing is to seek out the actual numbers carefully if you can find them. Because especially when people start to draw a picture to describe numbers – whether that’s with words or an image – all sorts of biases (and errors) come into play.

5. Don’t fall in trust at first sight with data visualization.

Data visualization can be totally enlightening in the hands of people who know both data and accurate visual portrayal well. (If you’re not already familiar with Hans Rosling, check out that master at work.)

But data visualization is also at risk of losing numbers’ objectivity. When colors, shapes and visual perspectives are added, they can distort – often even more than they clarify. Some techniques add optical illusions – 3D pie charts are a classic example.

And data visualization can accumulate all the problems in a distortion snowball. Unreliable data can be selectively picked out, all the data that explains the uncertainty stripped away, and then presented in a series of shape-shifting images that break all the rules and press all the buttons.

It’s tough to communicate risks clearly and fairly in a community where many have at least some number phobia or number fatigue. It’s tough to be rational about risk, too.

We might pay more attention to data that shores up our beliefs and rationalize away numbers that contradict what we want to believe. This risk is too small to bother with, we might convince ourselves – even though we’re very concerned about other risks in our lives that are in fact far, far smaller. We might convince ourselves that we’re uniquely invulnerable: because of personal luck or “good” behavior, that particular risk simply doesn’t apply to us.

Still, others will succeed in driving up our fears of things we probably wouldn’t worry about if we had the data in perspective. It doesn’t matter if the community has an exaggerated fear out of all proportion to their actual risk – there’ll still be people trying to raise our already over-high awareness. Olav Førde points to a critical risk: this probably doesn’t just affect our perceptions about each particular issue: it may make us less courageous. For that, there’s no shortcut. Bertrand Russell: “…to live without certainty, and yet without being paralysed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing that philosophy, in our age, can still do for those of who study it.”

Tolerance of risk and uncertainty are essential to a good life, too.

~~~~

Browse through my posts on risk-related themes (including the fear and attraction of risky winter sports).

To read more about techniques on presenting data in graphs and visualizations, this Wikipedia page is a good introduction to the ground covered in classics like Darrell Huff’s How to Lie With Statistics (free online) and Edward Tufte’s The Visual Display of Quantitative Information.

The cartoons (and Excel sheets) are my own (Creative Commons License): more at Statistically Funny.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Just came across this site. Love it. Will be coming back to learn and be entertained

Thanks!