“Just” Joking? Sexist Talk in Science

I’m a scientist who’s also a cartoonist. So I’ve got a pretty keen interest in scholarship and empirical research on humor. And I want to talk about research and sexist jokes, and where that leads. It’s a response to a narrative about the Tim Hunt situation that goes something like this:

It was just a joke. An unfortunate turn of phrase. It’s not that big a deal. He’s a nice guy who’s nice to many women – he didn’t mean to belittle anybody. It’s not demeaning if you don’t intend it to be. He’s eminent as well as nice, so give him a break. Lighten up. What has the world come to? Over the top social media firestorms are a worse threat than thoughtless remarks. Academic freedom/democracy is at stake.

I’ll start with research on the seriousness of humor and follow that thread through to the potential for effectively reducing sexism. I’m not going to talk about professional comedy. That’s a whole other kettle of fish.

Science is dominated by a narrow slice of the world’s demographics. It’s tough for “outgroups” to gain and maintain a foothold and respect.

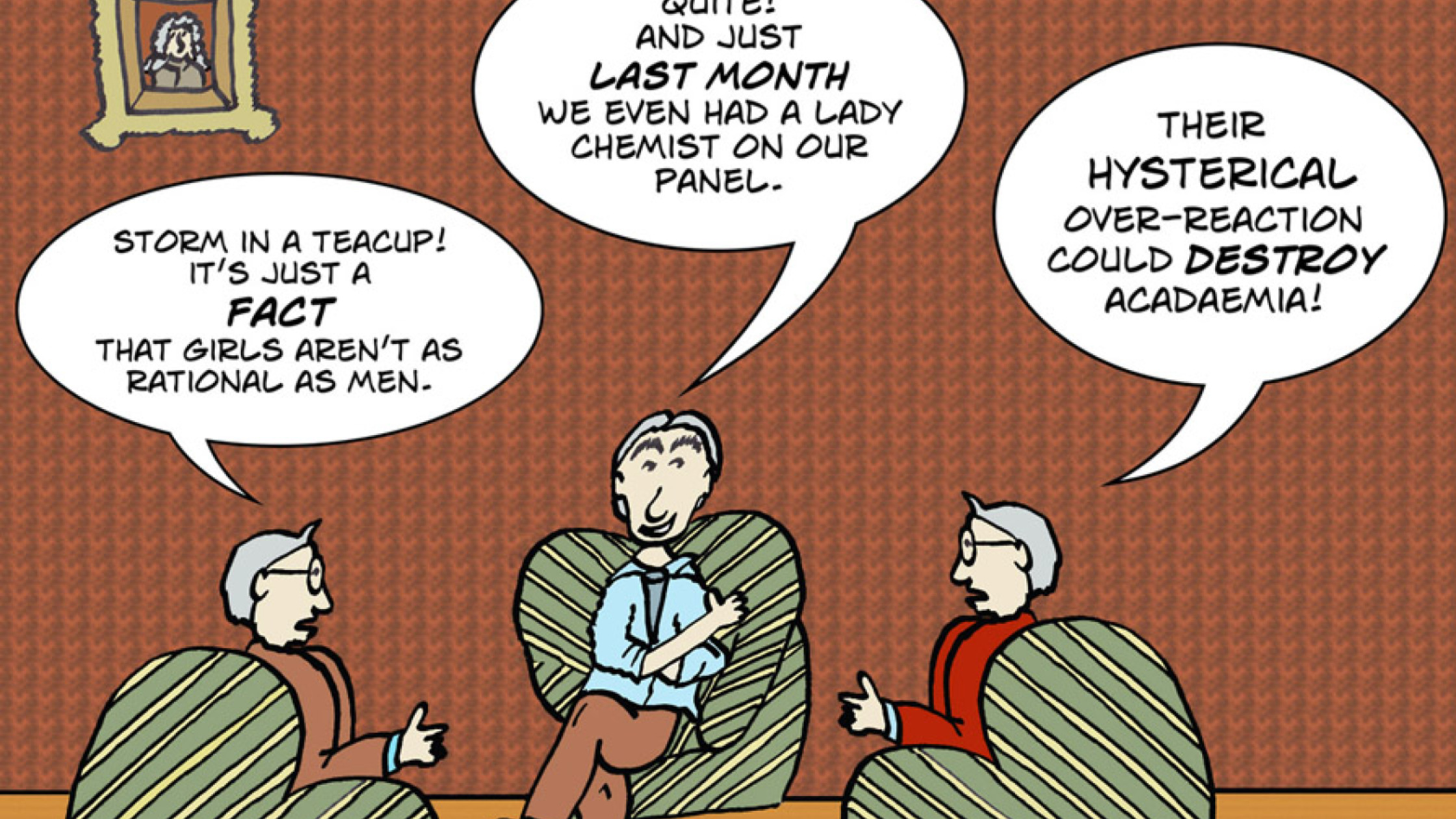

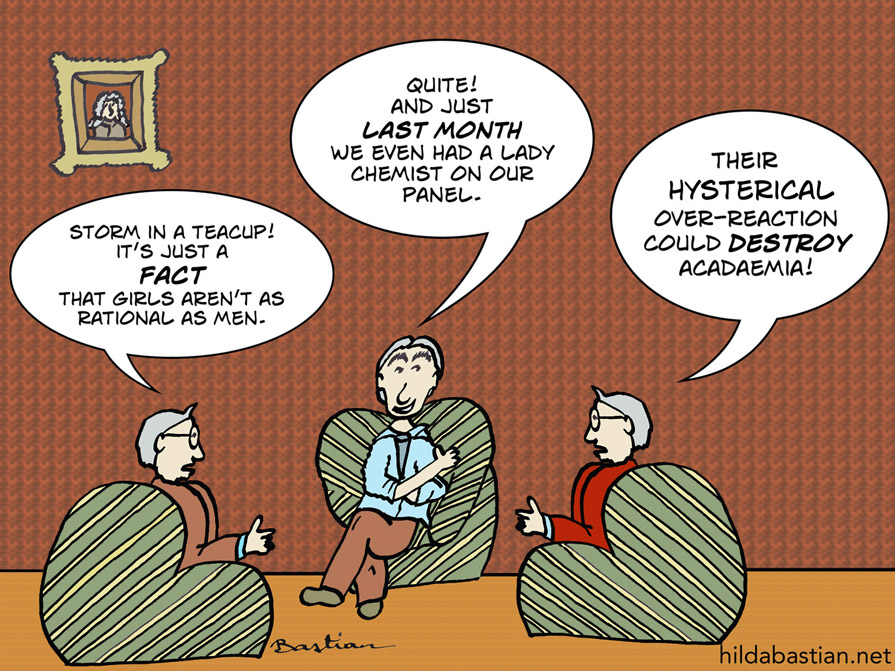

Humor can be used to create a quick bridge between people. But it can also reinforce outgroups’ otherness and relatively marginal social status.

In a 2004 review of empirical research, Thomas Ford and Mark Ferguson [PDF] point out:

Disparagement humor (e.g., racist or sexist humor) is humor that denigrates, belittles, or maligns an individual or social group…[P]eople have become less willing to allow joke tellers “moral amnesty” for their derision of social out-groups through humor.

Sexist and other discriminatory disparaging humor takes a code for granted: its funniness relies on people recognizing the stereotypes that are the basis for the joke. It asks us to not take discriminatory stereotyping seriously. That’s not going to take the sting out of it.

Ford and Ferguson concluded that jokes don’t create hostility to the outgroup where it doesn’t already exist. But the evidence, they said, showed that joking reinforces existing prejudice. If you joke about women and get away with it, those who are hostile to women will see this as social sanction for their views and behavior. The joke tellers don’t themselves have to be actively misogynist to end up encouraging others to be.

Sexist humor’s impact may also reduce people’s willingness to take action against discrimination. Take for example this randomized controlled trial of men recruited via Mechanical Turk, published by Ford and colleagues in 2013 [PDF]. Men who were already high in hostile sexism were less likely to express support for actions that would improve gender equality after hearing sexist rather than neutral jokes. Even if that only meant they were more willing “to show their hand”, it’s not reassuring.

A joke communicates something about the teller, and what they think is acceptable. If you haven’t listened to what Tim Hunt said on the day after the remarks that set this off (reported in detail by Deborah Blum), it’s worth listening to the two tapes here to get his take at the time.

[Update] On 18 July, The Times published a tape provided to them by another journalist who was at the lunch, Natalia Demina. It is a snippet of part of his remarks: Hunt included a statement with a very sincere wish that women not be harmed “by monsters like me”, that received a warm response. I’m sad that a person who clearly wishes women scientists well, nevertheless put a likable face on sexism.

The parts of his statements on the BBC tapes that portray women as difficult in the scientific workplace because of gender characteristics are sexist, as is calling young women scientists “girls”. That’s not dependent at all on whether the statement is a joke or not. If it’s not said with malice, then it’s just less hostile: but it’s still sexist.

The parts of his statements on the BBC tapes that portray women as difficult in the scientific workplace because of gender characteristics are sexist, as is calling young women scientists “girls”. That’s not dependent at all on whether the statement is a joke or not. If it’s not said with malice, then it’s just less hostile: but it’s still sexist.

When Hunt spoke/joked of the benefit of all-male labs, he was not hypothesizing some comic universe. There are all-male labs – and most labs are headed by men (including the ones at the Crick where Hunt wound up a lab in 2010).

Speaking of the Crick brings us to the issue of what role eminence plays. Should it mean you get more of a pass than someone else?

According to work by Jason Sheltzer and Joan Smith, elite male scientists may be even less likely than other men to employ women in biology labs. Anything that reinforces the message from their peers that this is in any way desirable isn’t going to help.

Sexist remarks and jokes form one of the constellation of factors that make up workplace gender harassment, mapped out by Emily Leskinen and Lilia Cortina with a group of experts in 2014. A 2010 systematic review and meta-analysis by Sandy Hershcovis and Julian Barling found that the higher the status of a person who is harassing, the worse the damage. That seems to me to be relevant to the public sphere as well.

Beneath the words “it’s just a joke” lies the implication that sexist talk itself is not really serious. That trivializes the burden of incivility and disrespect. Workplace incivility is psychologically stressful and forms part of the climate that allows discrimination against individuals to flourish (see Yang and colleagues’ 2014 systematic review).

A Nature editorial about Hunt’s remarks said that in science, “discrimination against women runs deep” in our psyches across gender lines. When it comes to everyday sexism, Janet Swim and colleagues suggest that people may not be able to see it clearly, though: “Perhaps people do not define themselves as sexist and conclude that the beliefs must not be sexist because they endorse them”. They found men hold sexist beliefs more often than women – and don’t experience sexism directed at themselves very often.

Socialization as women complicates sexist jokes, too. It’s not just that we may find humor in different sources, as Jennifer Hay points out [PDF]. But if women don’t laugh at men’s jokes, we’re told we don’t have a sense of humor.

Not being able to take a joke is also at the heart of the “just a joke” narrative. And it seems to me to be coded, too. To not laugh at a sexist joke, or to confront it, brings with it the risk of being branded a humorless or overly sensitive feminist…

There’s societal pressure after all, to be liked – and to be, well, ladylike, isn’t there? To be “a good sport” – even when people are insulting our gender: let’s not take the whole gender equality thing too seriously, right?

Saying women are somehow overdoing it in demanding gender equality and respect is itself a manifestation of modern sexism (see Susan Fiske and Michael North [PDF]). Asking women to lighten up about sexism, is really another round of sexist behavior, whether it’s intended to be or not. And increasingly, women who were concerned about the attitudes revealed have been targeted. (See postscripts and my later post, The Outrage Factor – Then and Now.)

Julia Becker and colleagues point to the need for “seeing the unseen” – understanding what everyday sexism really is. That’s not enough, though, to change sexist behavior – that requires empathy, as well. Gender bias awareness training has had some success in academic environments, including the WAGES program (studies summarized by Becker) and a cluster randomized trial reported recently by Molly Carnes and colleagues.

We need to make it safe to confront sexist behavior, though, especially when it’s coming from powerful and influential people: it hasn’t looked all that safe during the Hunt incident. Several authors in this field also write that we need to appreciate the benefits confronting everyday sexism can bring, like increased confidence. We confront sexist behavior far less often than we would like to think we do – maybe only half the time (some researchers peg it as even less often). Melanie Ayres and her colleagues show that young women’s willingness to confront everyday sexism depends partly on individual factors, and partly on the situation.

There are big differences in people’s willingness to take risks though, and that comes into play here. Taking this kind of risk with people in power in the workplace is one of the standard ways people’s relationship to risk is measured. Ayres argues that calling out jokes may be easier than calling out other sexist behavior. Perhaps it’s essential for gaining the confidence to tackle behavior that’s harder to confront.

The first step, though, is realizing that disparaging sexist remarks are in no way less serious in the form of a joke.

The second, it seems to me, is a societal problem. Yes, there’s a lot we can do to dismantle everyday sexism as individuals. But we can’t just expect people to take potentially serious risks with their careers, one by vulnerable one. We need better support for when they do. We need collective action, too, to enable social change. The internet and digital communication are unleashing torrents of sexist and misogynist ugliness on a scale we’ve never seen before. It’s also enabling a new wave of feminism though, writes Rebecca Solnit:

…building arguments comment by comment, challenging, testing, reinforcing and circulating the longer arguments in blogs, essays and reports. It’s like a barn-building for ideas: innumerable people bring their experiences, insights, analysis, new terms and frameworks.

We need to strengthen “feminists on Twitter”, not revile them. Gender equality is inherently disruptive to those comfortable with the status quo: anything other than almost imperceptible change will be discomfiting to many. We can’t know for sure, of course, what will bring us deep and lasting progress.

But it won’t come from being ladylike.

CODA: On 18 July, The Times published a snippet of a recording of Hunt’s remarks. I added a paragraph to the section with the other two tapes of Hunt speaking about this.

Part 2: The Outrage Factor – Then and Now

Part 3: A Tim Hunt Timeline: Cutting a Path Through a Tangled Forest (An analysis posted on my personal website on 27 July)

Part 4: The Value of 3 Degrees of Separation on Twitter

Part 5: The “Un-Calm” After the Tim Hunt Storm (Timeline followup)

[Postscript] For those following the twists and turns of framing of the Tim Hunt debate, this post was published on 22 June – two days before the theory about journalists conspiring to hide that the remarks were framed as a joke launched through the media. In fact, that he was joking had been central to the narrative from the first day.

On 30 June, epidemiologist and statistician Darren Dahly summed up the problem with Tim Hunt’s comments neatly:

For what value of X is the following joke acceptable? “The trouble with group X is that they always [stereotype 1 and 2]. Now seriously…”

[Postscript] On 26 June, the Provost of UCL (University College London), Michael Arthur, reaffirmed UCL’s decision on the incompatibility of Tim Hunt’s honorary post with the University’s commitment to equality and diversity:

An honorary appointment is meant to bring honour both to the person and to the University. Sir Tim has apologised for his remarks, and in no way do they diminish his reputation as a scientist. However, they do contradict the basic values of UCL – even if meant to be taken lightly – and because of that I believe we were right to accept his resignation. Our commitment to gender equality and our support for women in science was and is the ultimate concern.

[Postscript] (23 June 2015): Two excellent posts expand on themes I only touch on here. Suw Charman-Anderson’s post expands on the theme, “With great power comes great responsibility”; Emily Willingham’s on the trouble with calling criticism of Tim Hunt a witch hunt.

Liz Silva posted a poignant symbol on Twitter: the Crick Institute’s failure to acknowledge Rosalind Franklin. It’s worth pointing out here that despite its stated commitment to diversity, the 17-member Executive Management Team of the Crick includes only 3 women (none with scientific domains of responsibility).

[Postscript] (24 June 2015): Beginning with a report in The Times, a more pointed round of attack was opened up, this time particularly of the journalists who had reported the original comments. I added a recommendation to listen to the second tape (including the use of the word “girls” for young women scientists, which occurred in that second tape).

That so many feel so strongly that this should have no repercussions is an indicator of how deeply entrenched the tolerance of sexism is in science and society. Tellingly, at the time I wrote this, the comments at The Times singled out the two women journalists, but not the third (a man). And the race (and more) of one of the journalists was explicitly slurred, and allowed through The Times’ moderation (deleted following my complaint).

Correction: Thanks to Jim Woodgett for pointing out I’d misinterpreted a page at the Crick’s website: corrected on 24 June.

[Postscript] (1 July 2015): On 29 June, Uta Frith, chair of The Royal Society’s new Diversity Committee, wrote a most impressive post about the Tim Hunt episode, and their plans to improve diversity at The Royal Society. Not be missed.

~~~~

Another post me from on research into humor: one on science communication (Wocka! Wocka!)

The “Not a lady” photo is me at work at the NIH. It was taken at our Wikipedia edit-a-thon for Women’s History Month 2015.

[Update on 23 July] Disclosure: I am a (freelance) contributor at MedPage Today, whose global editorial director is Ivan Oransky, one of the journalists involved in reporting Tim Hunt’s remarks.

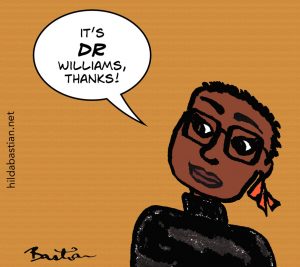

The cartoons are my own (CC-NC license). (More at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

One thing I would add that I think would benefit all people is if we don’t recognize a woman scientist for doing something as a woman scientist but, instead, as a scientist.

(Really confused sentence. Lemme explain.)

“Ruth Somegirl was the first woman scientist to create perpetual motion” vs. “Ruth Somegirl was the first scientist to create perpetual motion”

Joe, your example isn’t too good, because saying that Ruth Somegirl is the first woman scientist to discover perpetual motion, suggests that a man’s already discovered it 😉

“Saying women’s demands around gender equality and sexism are somehow overdoing it is itself a manifestation of modern sexism (see Susan Fiske and Michael North [PDF]).”

This statement seems to suggest that there’s no way a feminist can be overdoing it or called for doing so. In this sense, I think this sentence is actually overdoing it. Am I sexist for thinking so?

Note that I didn’t read the cited 93-page document, so I may be missing some context.

No, Steve, I don’t think your comment is sexist. Obviously it is possible for anyone to be unreasonable. Some kind of boundary of reasonableness is always assumed – although it’s not at all a simple thing to agree on where those boundaries are. We are a very long way from coming anywhere close to only having genuinely trivial things to worry about.

I’ve reworded that sentence to this: “Saying women are somehow overdoing it in demanding gender equality and respect is itself a manifestation of modern sexism…” I hope that does better justice to the concept, by focusing on the principles of equality and respect. Thanks for the comment.

I agree, Joe, that always describing people by their gender or gender characteristics is definitely a problem. Making male the norm, so that the exception of non-male must always be pointed out, is essentially marginalizing. Christie Aschwanden proposed “the Finkbeiner test” to address this with a checklist.

I personally wouldn’t like to see the “first woman to” entirely disappear. It’s ridiculous of course, when it goes too far, as your example is pointing to. But for certain barriers, like being the first woman admitted to a particular university, while it’s definitely not the case that the second, third, and fourth women (etc) didn’t have an equally (or possibly more) difficult time, there are two things about it that I like. Firstly, in a biography, it does tell you something about the woman: it can be a major achievement to break down a certain kind of barrier.

And it also provides a reminder of how long total domination of one gender survived (e.g. saying that Caroline Herschel was the first woman to get an article published in the Philosophical Transactions, in 1787, shows that the Royal Society managed to keep women’s work out of the record for over 120 years). Hearing that a professional milestone was only passed in the last 10 years or so, is a bit of a measure of that profession.

Like Steve, I disliked this sentence (even after the correction):

“Saying women are somehow overdoing it in demanding gender equality and respect is itself a manifestation of modern sexism.”

A demand, even when it is justified in principle, can be excessive. For example, one could be demanding excessive punishment for mild forms of sexism (e.g. people getting fired for wearing a fancy shirt). This is exactly what this article is about – the damage of mild forms of sexism, e.g. jokes, as opposed to more serious forms of sexism, e.g. not hiring or promoting someone due to gender. So I think it is important to get this right: yes, calling demands for equality excessive can be sexism itself. No, it isn’t always sexism.

Not all offenses are equal. Not all offenses even matter. To be sure, I do agree that jokes matter a lot and that, in general, small offenses made in public or social settings carry more weight than they seem to. But we must be wary of treating all sexist offenses as if they were identically bad.

Tom, I don’t think that the offenses need to be “identically bad” for their consequences to be serious: that’s what the research shows. And it is the consequences that matter. (Obviously, anyone getting fired from an actual job for unreasonable reasons should have legal recourse.)

1) Tim Hunt made a jocular observation that men and women working together in labs can be emotionally distracting for both sexes. Indeed, he met his own wife whilst working in the lab! (hence the deliberate irony in his comment)

2) Tim Hunt’s joke references his personal experience: a problem he has had, working in labs in the past, is that women tend to cry more when confronted with criticism. Nevertheless he fully supports women in science. “No one seems to mention his main speech in Korea in which, according to the ERC President, he was ‘very supportive towards women in science and he said that he hoped there was nothing that barred women from science’” (Dame Athene Donald).

3) After making his joke, Sir Tim continued: “Now seriously…”

4) Humour can be used to hurt or heal. We should always bear in mind the motive of the speaker. If a female scientist had indulged in some good-natured ribbing against male scientists, I’m sure people wouldn’t think twice about it. Sexism in science is indeed a problem but, occasionally, this problem can flow both ways.

Please follow the link below to read more on Sir Tim’s story and, if you agree, sign the petition to help reinstate Sir Tim Hunt:

Online Petition: Bring Back Tim Hunt!

We have over 1300 signatures so far, including comments by feminists, professors and former colleagues of Sir Tim. Please share this petition on Facebook and spread knowledge of it so we can hit our target of 2000 signatures!

Stephen, I’m not sure, from this, whether you have actually read the post. I’ll reply only briefing, because the research referenced in my post contradict your arguments fully – and you have cited no evidence for your claims.

1) The remarks that may or may not have been intended as a joke were sexist: being a joke wouldn’t make them less so. The only remarks he made were not those in Korea: he has expanded on them and detailed them as his “honest” beliefs on further occasions since. Describing women scientists as “girls” was also sexist. Speaking of a personal preference for segregation in science was also sexist.

2) There is no contradiction here. It is of course possible to hold sexist views without being totally hostile to women.

3) Doesn’t change anything. See the post.

4) Motives only determine the level of hostility. Intending no malice doesn’t turn sexist statements into non-sexist statements. Sexist remarks from prominent people in ambassadorial roles do particular harm. Brushing them off is totally counter to advancing women in science.

I find it very encouraging that despite the intensive widespread promotion of this petition, there are still less than 2000 people who have signed it.

Anyone who is at all interested in the petition being promoted here by Stephen Ballentyne should read Dorothy Bishop’s post analyzing the comments of people who signed it – and the comment there on what kinds of petitions Stephen has promoted in the past. Dorothy’s post addresses the issue of media distortion in the Hunt case.

I think there is a misunderstanding. The only thing I take issue with is your statement that it is sexist to call a feminist demand excessive. This is by any account a wrong statement. It is wrong because the consequences of offenses are not equally serious/bad, making it possible to overreact to a legitimate problem. I did not write or imply that jokes are no big deal; in fact I clearly wrote just the opposite.

This may seem like nitpicking – this is just one little sentence in a long essay. But it is a very bold statement, that I have heard in other places (and in other political movements), and even after it has been pointed out to you twice, your correction does not help. Having good intentions and fighting for the right cause does not make one immune to mistakes, and definitely should not make one immune to criticism. It is possible for somebody to object to a feminist demand and still not be sexist themselves. This remains true if the demand concerns an objective inequality between genders, for the reason mentioned above.

Hi Hilda,

Great post. I’ve a lot of respect for Tim Hunt and his research but was astounded by his remarks – amplified enormously because of his influence and stature. One thing to note, you link to an “all male” lab – at CRUK’s Clare Hall facility in the north of London: http://crick.ac.uk/research/laboratory-sites/clare-hall/ Those are the lab heads/group leaders which, in of itself, is a concern. However, those individual labs (to my knowledge) are mixed. The idea of segregation of any sort is antithetical to science.

Thanks so much, Jim – I thought it seemed awfully small! I’ve corrected that.

One other problem with “it’s just a joke” is that bullies say it when they get caught. The “joke” is rarely funny* and what’s attempted is to shift the onus of the insult from the insulter to the victim. “What’s the matter, can’t you take a joke?”

The sting of the barb isn’t soothed. The original barb hurt, after all, and hurting others for one’s own amusement won’t earn much sympathy. That’s just a form of emotional abuse.

*Note to Tim Hunt, if you’re going to tell jokes, try to inject a little humor into them. That makes it easier for people to recognize your jokes as jokes instead of insults.

How do media lynch mobs (social and traditional) help reduce hostility and create a bridge between ingroups and outgroups?

Hi Hilda

I agree entirely with this post. The “Now seriously” in the new version of events promoted by some does not change much to the discussion. Furthermore, this late recollection conflicts anyway with several journalistic accounts, so take my point below as a general comment about sexism/racism and humor rather than related to the Tim Hunt affair.

While a sexist/racist joke is sexist/racist, jokes about racism/sexism are not. To take one example, there is a long tradition of Jewish humor about Jews, a lot of it would be considered racist in the wrong context. Many of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons would also fit in this category. The new version of events could almost fit in this category, not because of the “Now seriously” but because of the self-deprecating nature of the concluding statement, i.e. be prepared, this is the kind of horrible stuff you will face. Again, I do not believe this to be relevant to the Hunt affair, since this is not what has happened (as is obvious both from other accounts and from the interview), but maybe relevant to the general discussion of this post.

Raphael

In defense of calling this a “lynch mob”:

We know what the outcome of these happenings will be. We’ve seen it many times. Context is lost, the target demonized, and careers and reputations destroyed. Even if no one explicitly calls for it, the outcome is a professional “lynching”.

We’ve already seen arguments that what happened to Tim Hunt may help reduce sexism in science. In other words, “pour encourager les autres”.

Your article – and much of the whole affair – makes me wonder if we speak the same language. I’m looking at the EU version of what Tim Hunt says and I can see nothing sexist in any part of it.

Tim starts by [pretending] wondering why someone like him has been invited to speak to that group. [In the rôle of that ‘monster’] he uses the language and views typical of scientists in his past referring to girls upsetting the laboratory routine. Now (today) seriously [out of that rôle] the real Tim Hunt congratulates the work that women do.

Now all that is OBVIOUS without the stage directions and is not the slightest bit sexist, misogynist, unreasonable, etc – in fact it is quietly saying thank goodness we are out of those old, nasty ways. I do not know Tim Hunt and I do not know what he had in his mind – but just going off what he said he sounds a reasonable and caring person of the type I might have hoped that my daughters would encounter in their careers.

What I find frightening are the many who look at the words, ignore the meanings and context, and cry “Sexist”. Their response is ignorant and leads to bullying of the nastiest sort. Certainly the self-claimed actions of Connie St Louis – in pushing institutions to respond and respond quickly appear to be of this order. I would be most concerned for any of my family to work in her vicinity.

What is most sad is that Tim Hunt appears to have realised his mistake and resigned himself to his fate. Not the mistake of being, or even talking, sexist but of allowing his casual words to be mangled and misrepresented.

Are we speaking different languages? Certainly the (more fully) reported comments seem typical of an Englishman of his age and entirely understandable to me (he is 6 years older than myself). Certainly I see not the slightest doubt that he has been most grievously misused.

Lee, even in quotes, the use of a term for violent vigilante torture and execution – generally as a racist form of terrorism – for the backlash to Tim Hunt’s comments is distasteful to say the least.

My post wasn’t about this, and I certainly didn’t suggest that demonizing an individual, or even disparaging one, was a way to build a bridge between ingroups and outgroups. What I have argued, supported by literature, is that any sanction of behavior such as Tim Hunt’s contributes to a culture of unfairness and hostility to women, as those who genuinely discriminate against women take that as sanction for their views.

If people don’t want to have their statements and actions being widely discussed, disputed, and possibly attacked in the public arena, then they don’t need to participate in speaking events with journalists on hot button issues, and seek to widen and extend the discussion via large media platforms. If you seek publicity on that scale, and engage in the kind of inflammatory statements that Tim Hunt made to the BBC, then you may get a reaction that’s damaging.

Tim Hunt, and everyone else, would have been far better served had he simply apologized – without expanding on his remarks to the BBC to try to justify positions on which he already had received strong negative feedback. Had he done so, rather than throwing something of a Molotov cocktail onto the BBC airwaves, his reputation would likely at most have been dented. And he could have come out of it with an enhanced reputation, if he’d reacted with some sensitivity.

We aren’t speaking the same language, John. What you’re calling “the EU version” (which is not some official record, but the notes of one person) is sexist: it communicates with stereotypical negative descriptions of women and infantilizes professional women. It seems you get to the view that it’s not sexist with some interpretation: but even with your interpretation, it’s still sexist. That is, it stereotypes women as a class of persons in a way detrimental to them. There’s nothing critical about the attitude, nor suggesting that he doesn’t still hold those views: he doesn’t say those views are in the past for him.

So no, I don’t believe that is “OBVIOUS”: and nothing about it says, quietly or otherwise, thank goodness we’re out of those ways – just, some women have succeeded despite it. Indeed, he confirmed, both to Deborah Blum and to the BBC, that while he expressed it lightheartedly, he did mean much of it “honestly” – and did not see it as history. That is “the real Tim Hunt” on the BBC – he is explaining what he said and meant. And it was what he said on the BBC that was responsible for the furore that unfolded.

I have sons, not daughters, but whether we’re talking about young women or young men, I disagree with you: I would not want my children to have bosses/supervisors who cannot manage the emotions arising from attraction in the workplace and who cross the boundaries. We have laws about this because it is extremely serious.

I disagree completely that those of us who regard the statements as unacceptable, as Connie St Louis did, lead to bullying of Tim Hunt “of the nastiest order”. There we’re speaking another language too. Some people went overboard, but I didn’t think there was much of that at all. On the other hand, what we were bombarded with – filled with obscenities and violent language, was appalling. As you’d expect, the sanctioning of these views by a well-respected Nobel Laureate unleashed considerable sexism and misogyny. Certainly the scapegoating of Connie St Louis was nasty – and what has been happening to her is bullying of the nastiest sort.

On the generational issue: firstly, that sexist remarks (and indeed behavior) are widely accepted among a group of people that dominate science and institutions is of grave concern for the present and the future – and that’s the point. Uta Frith has written impressively about that on The Royal Society’s blog. Secondly, it’s not at all inevitable that people don’t evolve socially as their communities evolve. David Colquhoun is older than Tim Hunt, is also a Fellow of the Royal Society and an honorary fellow at UCL: here he addresses just that issue.

Your argument rests entirely on not according Tim Hunt the respect of believing what he has said himself – on tape, without relying on anyone’s interpretation of an event that wasn’t recorded in shorthand or taped by anyone (including not by anyone from the EU). To do that is definitely misrepresenting him.

So, if a man says anything perceived as critical of women it’s sexism.

You, a woman, criticise Hunt. Sexism? Oh no, not if it’s true. Truism.

What is true? Sir Tim doesn’t treat women badly, nor does he suggest anyone should … he just talks too much.

No, a man saying things that stereotype, denigrate, puts down women as a group, it’s sexism. If I did that about men, it would be discriminating against men as a group, too. The only difference would be, that I would stereotyping a group more powerful than myself.

If I had criticized Hunt, it would be a criticism of one person – not a stereotype of all men. As it happens, I did not criticize him: I criticized his remarks. That’s an entirely different thing. A criticism of him would be a generalization such as yours, Dennis, “he talks too much”.

I make it very clear in the post that he doesn’t need to suggest anyone treats women badly, for people who do treat women badly to feel there is still high-level societal tolerance for denigrating women.

Very clever words. You don’t criticise him. I criticise him by saying he talks too much. Yet talking is what got him into trouble, not suggesting, not doing. You argue that’s enough due to the “still high-level societal tolerance for denigrating women”.

So really Sir Tim Hunt has been sacked and humiliated for being a member of the group men and the way some members of the group men might treat women (and what they might tolerate).

That’s sexism.

Again, Dennis, you’re making assumptions about what I think beyond anything I wrote here. I said nothing about whether I think he should have been “sacked” nor do I think he should have been treated cruelly. I argue that what he said is enough to do harm to others, and I don’t consider him the only person who matters.

If a woman in the exact same position had done precisely the same thing about women or men, I’d believe it would be sexist behavior and inappropriate. It’s unlikely, though, if said about men, that it would harm men (as far as I know from studies).

Seeking to end discrimination on the basis of gender is not sexism. What’s not being tolerated here is sexist behavior about scientists while speaking publicly (and making sexist jokes is sexist behavior).

Okay. Not sexism. Just prejudice. In this case against a man because he is a member of the group men.

Do you think Hunt’s dismissal and humiliation was a reasonable punishment?

Or are you just going to argue about the word ‘punishment’?

If you had examples of women scientists of such high status denigrating male scientists as an entire group without criticism – even without evidence that anyone would be harmed – then this might be a worthwhile thing to discuss. But while I see lots of evidence of sexism from women (and I object to it), I’ve never seen prominent women behave in this way about men – although I’ve seen prominent women be derogatory about women.

Hunt wasn’t dismissed: he resigned. As each side of each story on these resignations isn’t out there, I’m not going to comment on them.

Do I think the consequences to him were out of proportion to what he did? Yes, I absolutely do. I haven’t seen anyone suggest otherwise. That said, he is responsible for his actions at a journalism conference, and in interviews with national media outlets. In 2015, to start speaking about such sensitive issues in such a way, is a highly risky activity: he has himself used words like “stupid” about it. That of course doesn’t mean he deserved what happened to him, even if it is to a large extent self-inflicted. He entered into something that we know can’t be controlled by anyone once it starts.

That said, I think a lot of what happened could have been handled better. And that’s unsurprising. We’re just not good at dealing with this phenomenon yet. (See my second post on this issue). It’s also the case that he is not the only person who has suffered a great deal of abuse from the events he initiated, and the worst abuse was not directed at him. Indeed, the outpouring of not just sexism but misogyny, and racism, underscores why society can’t afford high level apparent sanction of sexist behavior.

That said, this is the case with life in general, isn’t it? Consequences are not all that often in equilibrium with actions. Many grievous massive errors result in no harm or consequence – and many small acts result in massive consequences. Think for example of a small error that results in wrong side surgery compared to a massive surgical error that luckily results in no harm. Life isn’t fair, and all we can do is to try to reduce the unfairness that harms people where we can. I wish there was a way to stop the daily harm against women and minorities without even any discomfort to anyone – and certainly without intentional cruelty.

Like many others, I think given the harm done by speaking in this way on those kinds of platforms, resigning from those kinds of positions was the right thing for him to do. Compounding the problem instead, by encouraging the unleashing of hounds on others, did both him and others harm that was avoidable. He could have responded to the original situation in a graceful way and been a very different kind of role model that would have greatly enhanced his reputation and influence. I wish that’s what had happened. I’d have been a vocal supporter had he done so.

But neither he nor anyone else had the benefit of hindsight or experience at the time. Hopefully the next time something similar happens – and there will be a next time – we’ll have learned from this awful experience.

Coupled with the closing remarks of Tim Hunt it is now utterly obvious to everyone that the criticism of him was, at best, misplaced. If his final words don’t make that clear to you then you are lying to yourself. It is now totally beyond ‘not speaking the same language’. As for Connie St Louis, the criticism of her is right; threats are, of course, quite unacceptable and should be referred to the message carriers or the police. That does NOT let her off the hook. She deliberately tried to damage Tim Hunt, going well beyond mere reportage, and must accept the fallout from such an attack. She cannot claim the ‘prestige’ of her professionalism in science, reportage, and teaching, and at the same time hide under the cloak of ‘not understanding’. Either she deliberately lied about Sir Tim in order to gain a ‘scalp’ for a cause or she is a poor example of a reporter and questionably not fit to pass on her ‘skills’ to new recruits to science reporting. If exceptionally she can find a third alternative then she needs to put her case fully and transparently in the public domain – and without any more delay. She is the aggressor here; she had the choice to go ahead with a ‘story’ which she had all the time in the world to check and research with no newspaper demanding copy. It was a claim that she pushed to the pre-known detriment of another human being. Whilst she maintains her claims, or sheds them only as proof demands their retraction, there can be no tears for Connie.

There were no barbs in what Tim Hunt said. It was self-deprecating humour. It wasn’t intended as a stand up comedian’s joke. None of your criticism is valid.

Hilda,

If you go around demonising people who voice words that you, in your self-importance, have decreed are sexist then you may find that you end up demonising your own supporters. In fact that’s precisely what you have done with Tim Hunt.

Try decency. Try assuming the best of people. Stop attacking those who don’t think or speak in exactly your conformist manner. Some of us might just be doing exactly what is right without fitting exactly to your prescription.

That the remarks that caused Hunt problems were not all that he said, has always been clear, John. Yes, I agree that anyone who publicly campaigns on an issue is responsible for their remarks too. But I don’t at all accept that if people have different views and recollections about events, that it necessarily means they are lying. Eye witnesses typically see and hear different things. Some recalled no laughter, no applause; some recalled both; some recalled one but not the other. (Hunt reported only “some polite applause” – I have no idea where he stands on the laughter issue.) But certainly my concern about the harm of his remarks to journalists has never been about how they were received, even if that has been a big deal to others.

I don’t believe you or any of us can have any insight into Connie St Louis’ motivations beyond what she has said they were, John, so I can’t agree with you. I believe the personal, extensive, racist, and misogynist attacks on St Louis deserve the fullest condemnation. That so many people who say they believe public shaming to be wrong, have engaged in so much of it themselves, is a stark indicator that their fury is not likely to really be about public shaming.

(Please note that I moderate comments here and may not continue this specific dialogue.)

Hilda,

I know this is many years later and you may not see this, but I want to say how much I appreciate the responses you gave to the detractors who’ve commented here. They were thoughtful, honest, assertive, and displayed empathy even for those commenters who defended sexist remarks with their own sexist remarks. I am a millenial, female engineer who is just finding her voice in calling out behavior from both men and women which reinforces gendered stereotypes that reflect real discrimination I (and other women) have experienced. The main reason I have felt empowered to do so recently is because a highly prominent male scientist pointed out sexist behavior that he saw enacted against me, so I know how impactful the verbalized ideals of respected men can be.

I know it’s difficult for most people –men.. women.. everyone, really– to see the harm that seemingly innocuous remarks can have when they themselves have not experienced the discrimination caused by the ideals that such remarks enforce. I hope to exhibit your patience and understanding in similar situations in the future. Though hopefully the future will be a world where discrimination is reduced to the extent that sexist remarks no longer carry the same weight that they have today (and consequently will save people like Hunt from the corresponding backlash).

Keep trailblazing =)