Flying Flak and Avoiding “ad hominem” Response

It was easy to work out where I stood in a fairly recent outburst of name-calling from one of the pillars of science. I’m totally a data/research parasite!

It wasn’t quite so easy to work out where I fit, though, in this week’s array of pejoratives by Susan Fiske, past president of the Association for Psychological Science.*

I don’t think I’m a “destructo-critic” or cyberbully, although that’s definitely in the eye of the beholder. I’ve certainly been accused of it. I’m sure, though, that all that research parasitism set me down the path to “methodological terrorism” and the online “self-appointed data police”. Exhibit A: my recent post, Psychology’s Meta-Analysis Problem.

Several others on this side of the science street have responded to Fiske’s broadside. Neuroskeptic asked where the line is between “destructo-critic” and constructive criticism, and how was this bomb-throwing supposed to help us find it?

Andrew Gelman and Chris Chambers tackled changing times in both standards of science and internet communication culture. Xenia Schmalz wrote from her early career researcher perspective on dealing with social media criticism, and Simine Vazire is another voice of experience, making critical points. (Those posts will lead you to more responses.)

Susan Fiske fired back at her pro-democratization of science critics in … Business Insider.

Her editorial was characterized by colorful adjectives, emotive nouns and verbs, and name-calling. In defending it, Fiske made this argument as justification:

I think the hostility toward me is an example of the phenomenon I’m talking about.

Actually, it’s not. Her writing had been about ad hominem attacks on people for their scientific work. And there was no science in her editorial. I’ll come back to that in a minute.

Secondly, it’s not solid ground to dismiss all the criticism as ad hominem attacks either.

The popularity of “He would say, that, wouldn’t he?” comes from the Prufomo affair, when a politician was trying to dodge a sexual scandal bullet. And it’s important for considering conflicts of interest and more.

You can go all the way to the beginning of formal logic and rhetoric to see this argument unpacked: Aristotle argued that the ethos of a speaker is relevant to the persuasiveness of what they have to say. The ad hominem fallacy is often invoked simplistically, but it’s complex terrain. (See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.)

When Fiske took a position as a spokesperson for a collective, and engaged in name-calling and invective against another very broad collective, especially without specificity and with some unverifiable statements, then the position and authority from which she did it was relevant. Just as mine is, as a meta-researcher, blogger, cartoonist, Tweeter, and moderator of an online forum (PubMed Commons).

But let’s discuss some of the statements she made that can be fact-checked. It’s her depiction of how science works. Letters to the editor, personal private requests to authors for data, editors ensuring peer review is respectful:

These venues offer continuing education, open discussion, and quality control.

Everyone with critiques should continue coloring inside the lines, because that works. Plus, she appeared to argue, there is no place for naming and shaming. I won’t deal with the second issue here: I’ve already posted on the strengths and weaknesses of that argument. And I don’t have a problem with arguing that we should work towards collegiality: that’s a personal hobby horse of mine too.

Fiske’s depiction of a well-functioning system of civility and quality control is at odds with the evidence, though. The “trash talk” she deplores didn’t emerge only with social media: it has always been there. For some vintage trash talk from science’s giants, see Robert Merton’s collection. Like the first Astronomer Royal calling Edmond Halley:

“a lazy and malicious thief” who manages to be just as “lazy and slothful as he is corrupt”.

Editors do not always keep it respectful or even scientific, either in peer review or in journals. The system of reviewer anonymity is an inherently unequal and problematic balance of power, allowing hidden conflicts of interest and bias to flourish unchallenged.

All editors do not filter and edit for inappropriate remarks. Journals haven’t been shown to guard against major forms of bias (see here and here). Examples? Consider that firestorm over the add-male-authors peer review. Or check out the litany here, and see if you don’t recognize many of your “Reviewer 3″s!

Here are some studies that challenge Fiske’s depiction of traditional science culture:

- Peter Gøtzsche and colleagues’ cohort study on letters to the editor:

Authors are reluctant to respond to criticisms of their work, although they are not less likely to respond when criticisms are severe. Editors should ensure that authors take relevant criticism seriously and respond adequately to it.

- Many journals don’t have letters to the editor – or they close them off in a short period of time. Contacting authors directly is to little avail when so many disappear – and their data disappears even more than they do: see the 2014 study by Timothy Vines and colleagues.

- See the 2006 study by Jelte Wicherts and colleagues, “The poor availability of psychological research data for reanalysis” or read about the struggles of systematic reviewers getting the basic information they need from authors in the background here.

- Willingness to share data may even be getting worse in some areas, as Christine Laine and colleagues found [PDF].

Dealing with flak is part of communicating your science or opinions, whether it’s a journal, a conference, a grant application, around the water-cooler or meeting table, or online. Here are my best tips for managing it.

1. Avoid the ad hominem response: your work is not you.

This is tough. As scientists, we are often particularly passionate about what we do. And that’s great. But what we say or produce is not us, and we shouldn’t take criticism of our work or our ideas personally.

Just because you take offense, is not proof that offense was intended. Trying to separate that out makes it easier to see past the words and into the actual content, and gain analytic perspective.

That said, insensitivity and lack of empathy is both insulting and damaging. Science involves people of diverse ages, cultures, genders, and disciplines. We have a lot to learn about each other and how to communicate in ways that get ideas across without diminishing people.

2. It’s ok to “pass” or say “I don’t know”.

I got a lot of feedback after this post on tips for women at science conferences. The most common issue was handling negative, difficult, or aggressive questions.

Watching people who deal with it with grace, in a way that suits your personality and culture, is a great way to learn techniques that you can practice – in your mind and for real. That gives you something to draw on when it happens. And it’s one reason why the lack of diversity in conference speakers, for example, is such a problem.

We need our own raft of ways of peddling while we think – as well as standard fall backs. “Good question! I’ll think about that and get back to you”, “we’re looking at that in the next stage of our work”. And “I don’t know” requires some confidence, but it’s one of the most sadly underused statements in science debates.

3. Look for kernels of validity.

Resist giving in to defensive emotion as much as you can: it clouds your vision. Use your analytical skills to hunt for the kernels of actual “data” in the words. No matter how poorly or rudely phrased it is, there might be something valuable for your work in there.

And when you should respond – you don’t always have to – the response is more useful if it is substance directed to substance.

4. Know and use your confidence builders.

Some are people to go to for support or advice. For me, there are also “go to” songs on my phone that summon my courage and psychological comfort going in – and ones I know playing over and over will bring back my equilibrium afterwards if it’s rattled. When I’m intimidated, I remind myself where I came from, and the reasons I do what I do: that’s the core that keeps my footing and propels me forward.

Maybe it’s just me, that even after all these decades, I can sometimes forget to reach for these till I’m already way anxious. Reminding myself of the building blocks of cognitive therapy helps too. (See here, for example – and more on do-it-yourself paths to preventing anxiety here.)

And celebrating and remembering the things that give you confidence might help too.

5. Stand on the shoulders of methodologists.

All aspects of science are weaker when we don’t build on the work that’s gone before. That includes when we handle critical questions or make critical comments. Drawing on research that underpins your argument – whether it’s in defense or critique – is worth the effort. So having it at your fingertips to refresh your memory or call on when you need it is a big help.

For me, blogging and online comments are a kind of constantly building personal bibliography that helps me find things quickly. For example, some of the studies I “cite” above in this post, come from this post.

And stand on the shoulders of the critics whose style suits you or you aspire to, too. Being original and going it alone are over-rated.

6. Be a good “bystander”.

Cyber-bullying is a genuine problem – just as bullying can be a real problem in labs and other science workplaces. And it’s far worse for some than others. Racism and sexism – alone, and worst of all, combined – make this most seriously a problem for the less powerful in science.

What’s more, it’s not a social media problem: it’s a cultural problem. Domination of science spaces by elites, and attacks on scientists by non-scientists in social media, are more critical problems than shots fired by the people Fiske takes aim at.

We need to develop our skills at countering bullying. We will often be bystanders, and how we act – or don’t – can be determinative for what happens, or how the target feels about it. (Long read from me about this on social media here).

You can encourage a speaker at a conference with your obvious supportive attention – or your body language when someone is attacking someone else. Maybe you can ask a question when there’s mortifying silence, or someone is the only one getting no attention in a busy poster session.

And even if you don’t want to buy into it when someone’s being attacked on Twitter or elsewhere, you can send a supportive signal: “like” something else they tweeted, or tweet something complimentary about their work. Anything to fill their “mentions” with light against darkness.

This is a slide from a talk I gave last week on openness and peer review. Science’s past is individualism, elitism, and secrecy. But it’s not our future.

Keeping our thoughts to ourselves, and keeping science behind closed doors, isn’t going to move us forward. Pushing the envelope, building our individual confidence and diversity, and collaborating in the open will.

A follow-up post after Nicolas, Xai, and Fiske published a study on bloggers in 2019:

“Destructo-Critics” and Mean Bloggers: The Study

* [Coda]: After the storm of criticism Fiske’s draft editorial received, the APS published this version in November 2016, with several comments. And at some point, a copy of that replaced the original version that was packed with pejoratives. See Neuroskeptic for quotes from that original.

In March 2017, Fiske spoke at the National Academies of Science’s Sackler Colloquium on reproducibility, including discussing an analysis she’s doing on blogs – that includes mine here at Absolutely Maybe. Which I learned from watching, as sitting waiting to be the speaker following her. Rather surreal. You can see the video of Fiske’s talk here, and mine here.

(In the social media discussion around the videos, I saw Simine Vazire’s excellent post for the first time, which I added to the post above on 21 March 2017.)

~~~~

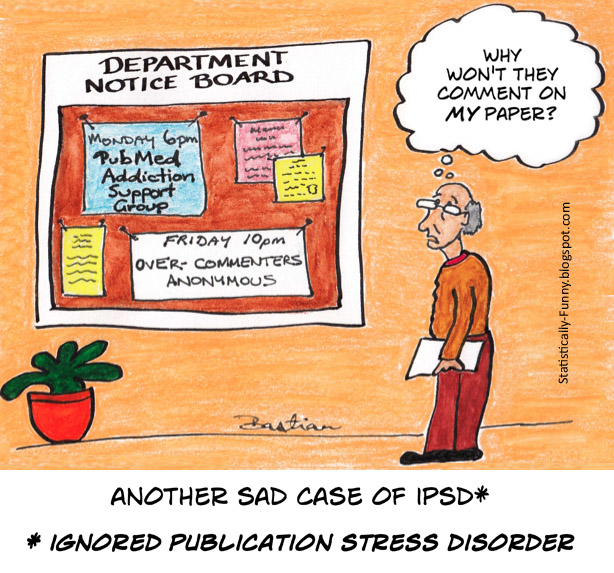

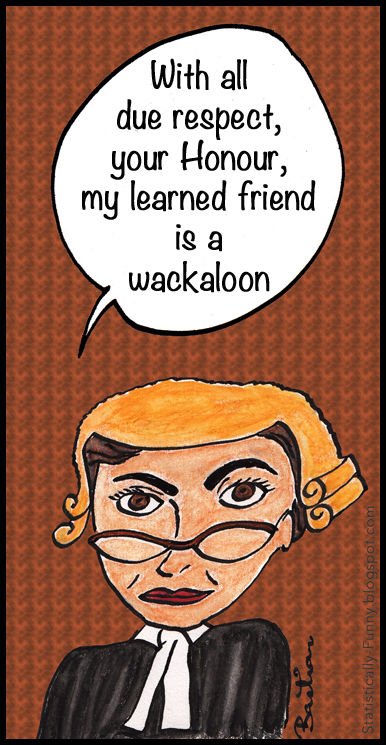

The cartoons are my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.