Down and Almost Out in Scotland: George Orwell, 1948, and Nineteen Eighty-Four

A tweet jolted me today. Doublespeak hit the news a few days ago, sending George Orwell’s final masterpiece, Nineteen Eighty-Four, back into a bestseller list.

It was the anniversary of Orwell’s death this weekend, too. The bleakness of that book is inseparable, not just from the political oppression that inspired it, but from his struggle for life while he wrote it.

The place Eric Blair/George Orwell worked on the book could be a bit bleak too – a house called Barnhill, on Jura, an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland.

The post below tells the story of his illness and treatment, in the context of a major historical change in clinical research – and his work on Nineteen Eighty-Four. (It was written for the James Lind Library in 2004.)

I brought a chest specialist here. He says I have got to go into a sanatorium, probably for about 4 months. It’s an awful bore, however perhaps it’s all for the best if they can cure me.

George Orwell, Jura, Scotland, December 1947 – Letter to Celia Kirwan.

On Christmas Eve 1947, Eric Blair (pen-name, George Orwell) was admitted to Hairmyres Hospital near Glasgow.

George Orwell was a journalist and novelist, and the publication in 1945 of his political fable, Animal Farm, had made him famous. He was 44 years old, and tests at the hospital confirmed that he had infectious chronic tuberculosis (TB) in his lungs.

Orwell has been described as “a representative of truth-telling, objectivity and verification”. As with other events in his life, he carefully analyzed and documented his experience of care for his tuberculosis, including his time in a private sanitorium.

Orwell had been given treatments that were common for TB in Britain at that time: ‘collapse therapy’ and other painful surgical procedures to keep the lung disabled to ‘rest’ it, vitamins, fresh air, and being confined to bed. The hospital staff confiscated his typewriter and told him to stop working but they didn’t seem to advise him to stop smoking!

Orwell’s work, a novel he would struggle to complete in the coming year – 1948, was Orwell’s “last great obsession” (1991). He twisted the numbers of that year to give the book one of the most famous titles and powerful symbols from the 20th century: Nineteen Eighty-Four, introducing Big Brother and words like ‘doublespeak’ to the international political and social landscape.

Orwell was hopeful:

This disease isn’t dangerous at my age, and they say the cure is going on quite well, though slowly… We are now sending for some new American drug called streptomycin which they say will speed up the cure.

George Orwell, Hairmyres Hospital, Scotland, February 1948 – Letter to F.J. Warburg (publisher).

Streptomycin had had a dramatic effect on tuberculous meningitis (MRC 1948a), a form of tuberculosis that was always fatal. It seemed to be the first real hope for a cure for TB of the lungs. With heavy pharmaceutical company investment, little time elapsed between 1943, when laboratory guinea pigs had responded positively to the new drug, and adoption of the drug by doctors in America for their patients.

There were some experiments in humans in between, but no formal trial, and thus no way of knowing for sure just what this drug was going to do in people with TB of the lungs. It went on the market in 1946, heavily promoted, and demand for the new ‘miracle drug’ was enormous (MRC 1948a).

If Orwell had lived in the USA, he could have got streptomycin on prescription as soon as his TB was diagnosed. As it was, it would take many years until companies in the UK could start producing the drug, and post-war Britain had too few US dollars to buy much of it: 50kg was all the government could afford to bring into the UK. The government was “besieged” by patients and doctors requesting streptomycin, the BBC started broadcasting emergency appeals for it, and soon there was a black market for the drug.

Austin Bradford Hill, working at the UK Medical Research Council (MRC), had already used randomisation to generate comparison groups in an assessment of whooping cough vaccines (MRC 1951), and he had been waiting for an opportunity to use this element of the emerging design of fair tests in an assessment of treatments.

Random allocation of patients to receive some of the limited supply of streptomycin was an equitable way of distributing the drug. It was also the way to find out more about the magnitude of streptomycin’s beneficial effects in a form of TB from which many people recover spontaneously, and about the drug’s unwanted effects, including the development of drug-resistant forms of TB. The first patients entered the trial in 1947.

Orwell’s hospital was not one of the hospitals in the trial: in fact, no Scottish hospital was included (MRC 1948b). That didn’t make any difference for Orwell – he wouldn’t have been eligible to participate in the study for several reasons, including his age (he was too old).

However, even with narrow entry criteria, the trial did help many people. Instead of languishing for months on a waiting list, being chosen for the trial meant that people were admitted to hospital within a week, even if they weren’t going to end up in the group of patients randomized to receive the drug.

Orwell’s specialist, Bruce Dick, recognized that Orwell’s social and political connections might help him obtain the drug outside the trial. In February, Orwell wrote to his publisher friend, David Astor:

Before anything else I must tell you something that Dr Dick has said to me. He says that I am getting on quite well, but slowly, and it would speed recovery if one had some streptomycin (STREPTOMYCIN). This is obtainable in the USA, and because of the dollars the B[oard] O[f] T[rade] (or whatever it is) won’t normally grant a licence. He suggested that you with your American connections might arrange to buy it and I could pay you…for it is a considerable sum and of course the hospital can’t pay it….

Orwell followed up later with an urgent telegram to David Astor, who responded promptly. Astor contacted Orwell’s specialist and urged him to ignore Orwell’s scruples about money and to deal directly with him (Astor).

Astor also contacted the Minister of Health, Aneurin Bevan (who had been Orwell’s former editor at the socialist magazine The Tribune), to make sure that there would be no political or licensing problems. A bank account in the US containing the proceeds of the sale of Animal Farm there provided the dollars. It only took Orwell a few weeks to get the streptomycin. Thus it was that Orwell became the first person in Scotland to be offered the opportunity to try streptomycin.

I am a lot better, but I had a bad fortnight with the secondary effects of the streptomycin. I suppose with all these drugs it’s rather a case of sinking the ship to get rid of the rats.

George Orwell, letter to Julian Symons, 20 April 1948.

The report of the streptomycin trial concludes that: “Toxic effects of Streptomycin therapy were observed in many patients, but in no single case did they necessitate cessation of treatment” (MRC 1948a). It is not known what the patients in the trial thought about the treatment. While none of them had to abandon treatment because of toxicity, George Orwell did. One of the doctors caring for him described it this way:

He was given 1g of Streptomycin daily and appeared to be making some clinical response, but after a few weeks he developed a severe allergic reaction with dermatitis and stomatitis. He wrote an excellent description of this in his notebook, he could not receive any more of this drug.

Orwell donated the leftover drug he could not take to the hospital. It was given to two doctors’ wives, both of whom recovered from their tuberculosis.

There was no place, though, for Orwell to register his voice and experiences of the treatment in 1948. Dermatitis and stomatitis may not sound too awful, but one of Orwell’s biographers concluded that “The side-effects had been horrible”. This is what Orwell wrote about it in the last notebook he would ever keep:

Before I forget them it is worth writing down the secondary symptoms produced by streptomycin when I was treated with it last year. Streptomycin was then almost a new drug & had never been used at that hospital before. The symptoms in my case were quite different from those described in the American medical journal in which we read the subject up beforehand.

At first, though the streptomycin seemed to produce an almost immediate improvement in my health, there were no secondary symptoms, except that a sort of discoloration appeared at the base of my fingers & toe nails. Then my face became noticeably redder & the skin had a tendency to flake off, & a sort of rash appeared all over my body, especially down my back. There was no itching associated with this. After about 3 weeks I got a severe sore throat, which did not go away & was not affected by sucking penicillin lozenges. It was very painful to swallow & I had to have a special diet for some weeks. There was now ulceration with blisters in my throat & in the insides of my cheeks, & the blood kept coming up into little blisters on my lips. At night these burst & bled considerably, so that in the morning my lips were always stuck together with blood & I had to bathe them before I could open my mouth. Meanwhile my nails had disintegrated at the roots & the disintegration grew, as it were, up the nail, new nails forming beneath meanwhile. My hair began to come out, & one or two patches of quite white hair appeared at the back (previously it was only speckled with grey).

After 50 days the streptomycin, which had been injected at the rate of 1 gramme a day, was discontinued. The lips etc. healed almost immediately & the rash went away, though not quite so promptly. My hair stopped coming out & went back to its normal colour, though I think with more grey in it than before. The old nails ended by dropping out altogether, & some months after leaving hospital I had only ragged tips, which kept splitting, to the new nails. Some of the toenails did not drop out. Even now my nails are not normal. They are much more corrugated than before, & a great deal thinner, with a constant tendency to split if I do not keep them very short. At that time the Board of Trade would not give import permits for streptomycin, except to a few hospitals for experimental purposes. One had to get hold of it by some kind of wire-pulling. It cost £1 a gramme, plus 60% Purchase Tax.

Orwell, at a private sanatorium in 1949, got to try PAS (para-amino-salicylic acid), the next anti-tuberculous drug to be introduced (1950):

This PAS stuff makes me feel sick but otherwise doesn’t seem to have secondary effects. One is very well looked after here but the doctors pay very little attention…However, I suppose they know best…They can’t do anything for you, but I want an expert opinion on how long I am likely to live, because I must make my plans accordingly.

George Orwell, letter to Sir Richard Rees, January 1949.

PAS did not work for him either. It would be a few more months till he gave up hope in the treatments available to him, though, after another bad experience with streptomycin:

They are going to try streptomycin again, which I had previously urged them to do & which Mr Dick thought might be a good idea. They had been afraid of it because of the secondary effects, but they now say they can offset these to some extent with nicotine, or something, and in any case they can always stop if the results are too bad.

George Orwell, letter to Sir Richard Rees, April 1949.

..This time only one dose of it [Streptomycin] had ghastly results, as I suppose I had built up an allergy or something.

George Orwell, letter to T R Fyvel, April 1949.

It looks as if I may have to spend the rest of my life, if not actually in bed, at any rate at the bath-chair level. I could stand that for say 5 years if only I could work.

George Orwell, letter to Anthony Powell, May 1949.

“If only I could work.” His frustrations about this are ever-present in his letters from 1948 until his death in January 1950. Early on, it wasn’t only personal and intellectual frustration. He was making a living for himself and his son as a journalist, and he was not yet so well-off that he could afford to go months without working.

As critics of the sanatorium had long ago pointed out in France, the common practice of confining ‘breadwinners’ to bed for months at a time had serious consequences for most people with TB (1995). Indeed, socialists in France had opposed the focus on sanatoria as an inappropriate response to the problem of tuberculosis. Sanatoria were regarded by them as “a resort scam for the rich and a smokescreen for the working class”.

There were not enough places in sanatoria for everyone, months without work made people destitute, and the funding of sanatoria meant that there was less investment than there should have been in addressing the social conditions associated with TB. A decade later, MRC researchers in India published the results of a randomized trial comparing home and sanatorium treatment. This found that households whose breadwinner hadn’t entered a sanatorium were less likely to suffer reduced income, family breakdown and other serious social problems, without any disadvantages in terms of recovery from the disease.

But that was not known at the time that Orwell was ill.

I am really very unwell indeed & am arranging to go into a sanatorium early in January…I ought to have done this 2 months ago but I wanted to get that bloody book finished.

George Orwell, letter to F J Warburg, 21 December 1948.

He did get Nineteen Eighty-Four – “that bloody book” – finished, and it was a masterpiece. However, he thought it was “a good idea ruined” – “I ballsed it up rather, partly owing to being so ill while I was writing it”.

FJ Warburg rushed the book into print, and Orwell got to see the great success and controversy it met with before he died from the complications of TB several months later. He was still consumed with the desire to write: “I must try and stay alive for a while because apart from other considerations I have a good idea for a novel”.

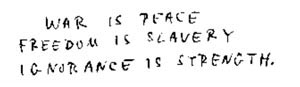

It’s impossible to know if he could have lived longer, or left us more of his thoughts, if there had been more knowledge then about how best to live with TB. That final book, though, made Orwell’s thoughts on the need for community access to unbiased knowledge clear: keeping the truth from people, or distorting it in someone’s interests, were pillars of evil in the totalitarian state he depicted. Or, as he wrote it in his cynical parody of political doublespeak:

~~~~

Acknowledgment: I am very grateful to Professor Jimmy Williamson, one of the doctors who provided care for George Orwell in 1948, for his account of Orwell’s care, and for comments on a draft of this story. I am also grateful to Professor Williamson’s son, Michael, for his assistance. And I’m grateful to Sir Iain Chalmers, for getting us together, as well as editing and publishing the original story on The James Lind Library in 2004 – and shepherding it into the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (2006).

Photo of George Orwell’s grave by Brian Robert Marshall in 2007 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Photo of Barnhill in Scotland by Ken Craig in 2005 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Photo of George Orwell at the BBC in 1940, BBC, uncredited (via Wikimedia Commons).

Photo of Hairmyres Hospital by Elliott Simpson (via Wikimedia Commons).

Cover image for the first edition of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four published by Secker and Warburg in 1949, from Brown University Library (via Wikimedia Commons).

Doublespeak snippet from the manuscript of Nineteen Eighty-Four from Brown University Library.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Thanks. Great blog. A treat to read about my favourite author as a pharmacist working in Infection.

Thanks for this. I studied George Orwell for my English exam in my final year of school. I wish he was around now to write about “Fake News”.