Bias in Open Science Advocacy: The Case of Article Badges for Data Sharing

I like badges – I have a lot of them! I’m also an open science advocate. So when a group of advocates declared their badges for authors were dramatically increasing open practice, I could have been a lock for the cheer squad. But, no, I’m not. In fact, I think the implications of the badge bandwagon are concerning.

These headlines and a tweeted claim will give you an idea of the level of hype around badges for sharing data and materials in science articles:

Simple badge incentive could help eliminate bad science. (Ars Technica)

Digital badges motivate scientists to share data. (Nature)

Even psychologists respond to meaningless rewards: All they needed to be more open with their data was a badge showing they did it. (FiveThirtyEight)

Data shows the effect of badges on transparency is unrivaled by any other known intervention. (Tweet)

That last one is a stunner, considering other known interventions include mandating data transparency as a condition for funding or publication! That tweet could take us straight to the issue of whether the badge policy pathway is ultimately good or bad for open science. And that a scientist said that goes to the peril of being a “true believer”. We’ll come back to those. But let’s start with the data people are talking about, and what these badges mean for us as readers.

The source of this was a paper by Mallory Kidwell and colleagues in PLOS Biology, called “Badges to acknowledge open practices: a simple, low-cost, effective method for increasing transparency”. The developer and prominent social marketer of the badges is the senior author of that paper and head of the organization tied to them, Brian Nosek.

The title has most of the authors’ strong claims embedded in it. They are:

- The intervention studied is simply offering a badge if authors meet certain criteria.

- The intervention is “low cost”, “low risk”, “relatively resource-lite”.

- There are no other repercussions – “if badges are not valued by authors, they are ignored and business continues as usual”.

- Badges are “dramatically” effective – dramatic(ally) appears 9 times in the paper.

- Badges increase authors’ use of the kind of repository the badges exist in part to promote – like that of Nosek & co’s Open Science Framework (OSF).

The paper reports what seems to be the only study on this. It involves looking back at what happened before and after a prominent journal, Psychological Science, introduced badges in January 2014. To gauge whether any changes observed might be happening in the discipline anyway, the authors chose 4 journals that did not have badges for comparison.

They then collected data on open-ness of data and study materials from all 5 journals for research-based articles from 2012 to May 2015: 2 years of “before” data and 17 months of “after” data. Let’s look at the authors’ 5 claims and see whether the data support them. The open data for the project were a big help, so the authors get lots of brownie points for walking the open data talk.

Claim 1: Was the intervention simple badges and criteria for them?

No. And that’s pivotal, because any effect could be because of co-intervention(s), not of badges alone.

The badges were among a set of changes at the journal in January 2014. And there is no way to pick apart the contribution of the badge, if anything else could affect the proportion of authors able or willing to share data and materials.

The badges paper does not mention the co-interventions, so you cannot rely on it to understand what they studied. They have no citation at all where they state the journal introduced badges. Here’s the journal editorial that explains what happened from January 2014.

Badges were 1 of 5 initiatives introduced simultaneously. The initiatives were all directed at improved research reproducibility. They all had implications journal-side, and they all could have influenced authors’ decisions to go ahead and publish in Psychological Science, in ways that could affect the journal’s portfolio of research. Remember, to consider confounding variables, we’re looking for anything that could deter or incentivize publishing at the journal. Here are the 4 initiatives other than badges:

- Methods and results reporting were removed from the word limits, because of raised expectations for rigor and reporting quality.

- The evaluative criteria for editors and peer reviewers were changed, upping the importance of the description of methods and evaluating them stringently.

- 4 new items you have to detail and confirm were added on the article submission form, including confirming that you have reported all exclusions, that your manuscript reports all independent variables and manipulations you analyzed, and confirming your manuscript reports sample size calculation and data collection stopping rules.

- A move away from statistical significance, with expectation that analyses conform to what they call “the new-statistics movement” (with a tutorial for that). (Here’s my quick explainer on that issue.)

This represents a much more profound change on the editorial side than just adding a badge opportunity. And if the authors able and willing to do any of this, are associated with being an author who has data and materials in share-able state (including any required permissions), then the co-interventions and any interplay between them are potential contributors to any outcomes observed. Add to these interventions at the journal, the social marketing of the badges launch by influential open science advocates (ostensibly) independent of the journal.

To isolate the impact of badges, you would need groups that had the same conditions except the badges. One comparison group would then have compliance publicly shown only with words; another would have all the same criteria, but no public reward.

Claim 2: Adding badges is low cost.

There was no data on this. The resource implications for journal staff and peer reviewers were not discussed. Some of the co-interventions appear resource-intensive for journals, both in establishment and implementation.

Then there’s the really big question: cost for authors, on whom the bulk of effort here lands. The badges-get-you-huge-bang-for-not-much-buck has become a major part of the social marketing strategy for open science, hasn’t it? Yet, high quality open data practice is a lot more effort than not.

The entire package, or even just the requirements to get a badge, would be resource-intensive for any authors who aren’t already open science practitioners and into what they call “new statistics”. And the impact of that probably lies at the heart of what we will look at under the next claim.

Claim 3: There were no other repercussions.

To be clear, the authors definitely did not state there was an absence of other repercussions. They just seem to have assumed that there wouldn’t be, and didn’t report a plan for identifying unintended effects.

One issue jumped out with neon lights flashing and bells ringing as soon as I started looking at the data, though. It’s not in the paper, as absolute numbers are sparsely reported there. The paper focuses on percentages.

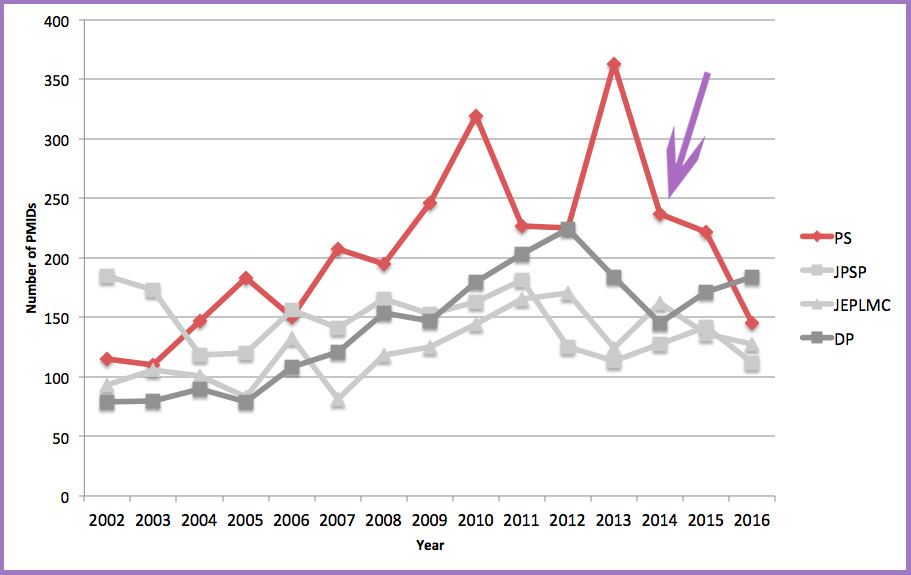

A part of why the percentage of articles reporting open data increased at Psychological Science (PS) was the denominator dropping: after January 2014, they published considerably fewer articles in total.

Productivity: Psychological Science (red) & comparator journals publishing 2002 to 2016 (PubMed IDs)

The data for this chart are here. It doesn’t come from the badges study data. That’s for 2 reasons. The time period was too short – I couldn’t think about what the data might mean if I couldn’t see it in the context of longer trends, because the number of events per journal is so small. (There are only 3 comparator journals, because one didn’t start publishing till 2013. Note too that this is PubMed records, so it includes non-research items in journals.)

Journals in psychology were rocked by a crisis in 2011. That’s what spurred the intense interest in improved methods and reporting in this field. At Psychological Science, it turns out, after having retracted only 1 article ever before 2011, between 2011 and 2012 they retracted 9.

Secondly, the badges study counts the time of publication by inclusion in a “print issue” list of contents – not when the article was actually published (the e-published date). It was March 2014 before any post-2013 articles appeared, and May 2014 before the first badge was awarded. The basic trend is the same, either way. And the upshot is that in 2016, according to PubMed, PS was publishing far less than half the items it published the year before it introduced the new policies (from 363 to 145).

Why? Without more data on practice and policy at PS, there’s not much to go on. This would be consistent, though, with the new policies deterring authors who didn’t already practice open science. There wasn’t a major discipline-wide drop in article production. One of the competitor journals has overtaken PS, and new journals started.

Of course, with so many co-interventions, you can’t say it’s the badge-related criteria that reduced article production so much. But if you’re going to claim the benefits of more articles with shared data and materials, then you have to own the drop in journal productivity (and its potential implications) too.

Claim 4: Adding badges alone is dramatically effective.

There is a lot I could say here, but I will limit it to a few key points. We’ve already seen some of those above: there are too many co-interventions to know what contribution badges made. And the increase in sharing without considering productivity exaggerates the impression of effectiveness.

It all suggests to me that the predominant effect we’re seeing here is a form of “natural selection”, with the journal ratcheting up its standards and possibly rejecting more, and its new systems potentially repelling less “open” authors. It would be really helpful to know what happened to submission and rejection rates at PS from 2010 onwards.

It seems from a superficial look at the data that the authors of 28% of the articles that qualified for badges apparently rejected the offer of the badge. If that is the case, this undercuts the badge as an incentive, too. The absolute number of badges was so small, though, and the timeframe so short, that all the data have a very high risk of bias. (To help put it in perspective, the mean number of badges in the last 6 months of the study was 4.4 a month; the 6 months prior, it was 3.7.)

The methods of the study have a high risk of other forms of bias as well. For example, although the authors went to a lot of effort to make sure the different coders were in sync, there was only a single coder for each study. In my neck of the woods we would consider that a high risk of bias, especially coupled with not being blind to which journal articles came from.

The reporting also has a high degree of researcher spin, which always sets off alarm bells – like an abstract with no absolute numbers, and full text without showing proportions with absolute numbers.

The longer I looked at the data in this study and its context, the harder the impact of badges became to discern. And the relevance of this data to areas outside psychology was problematic too. Studies with no need for a data availability statement because all the data is in the paper and supplementary files can be common in some study types, for example.

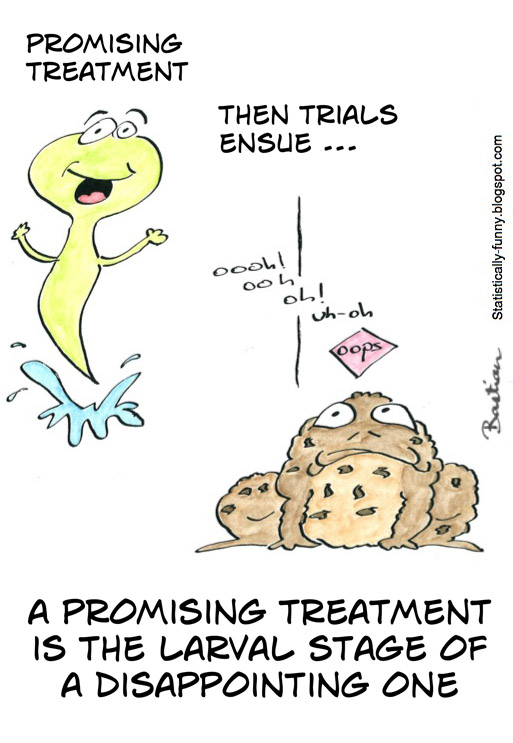

It doesn’t mean of course that badges have no effects, especially when accompanied by intense marketing by opinion leaders. But interventions hyped from uncontrolled research generally speaking don’t turn out to be as “dramatic” as their proponents believe. And with funders increasing their requirements for open data, the waters here have been getting murkier.

Claim 5: Adding badges increases use of independent repositories.

This is part of the intent of the intervention, designed, as it was, by an independent repository group. I didn’t look at the data on this question. Let’s just assume it achieves this aim as they say it does. And move on to what all this means – for us as readers, and for open science.

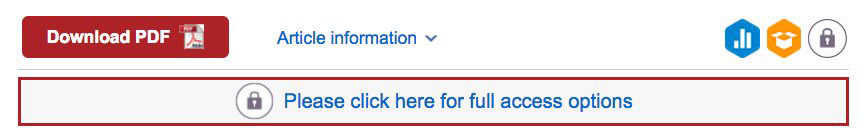

It was encountering these badges as a reader recently at Psychological Science that propelled me into writing this post. The marketing hype from advocates had disturbed me ever since this clearly weak study came out. But it coalesced into concern seeing it in action, and engaging with the badge group on Twitter about it.

Here’s what the article in question looked like at home:

Open data badge, open materials badge – on a closed access article. (The open data wasn’t included as supplementary material and nor was there a link to it outside the paywall. To their credit, they are going to try to organize accessible links in response my complaint.)

Here’s what the article looked like at work, where we have a subscription to the journal:

For anyone with a subscription viewing this, there will be the impression that these authors are practicing fully open science. They are not.

The Twitter conversation about why the open data/materials badges are so limited, ended up with the argument, it’s so high impact closed journals can say they have/move to more open practices – and that access to articles isn’t a problem for open science.

I don’t think the argument that an article is not part of a study’s data flies. It’s as though we’ve moved from saying the paper is the study, to the paper isn’t even part of the study! And open, for data and materials, is defined here in such a way that you can leave essential data and methodological information behind the paywall – and still gain open practice badges.

Part of the reason for openness of studies’ artifacts is to enable critical appraisal – the kind I just did. And not only from people with subscriptions.

Sometimes, you understand more from a study’s data than the paper – if you have the time and skills. But usually, you need as many artifacts as you can get. What’s more, if the authors stick to the specific criteria needed to get an open badge, then they can leave out data they didn’t analyze for the paper but which is essential to check on their analytical choices and interpretations.

Funders’ open data requirements aren’t so limited, and that matters. A large part of what the people who use data from others’ previous studies are studying has nothing to do with the authors’ original analyses. In this analysis, over 70% of requests for clinical data from a repository giving a reason was, asking new questions.

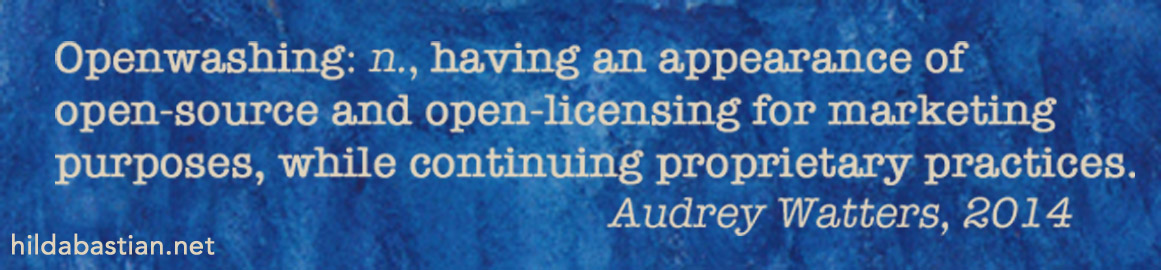

One of the most compelling talks I’ve ever heard about open-ness was by Audrey Watters, at Open Con 2014. (Check out the blog post at that link even if not the full talk.) She eloquently spelled out the dangers of openwashing. A bit like people prominently badging high sugar foods as “low fat”.

The version of data and materials sharing attached to the open badges isn’t the only path here. There are funders’ mandates and Dryad’s Joint Data Archiving Policy (JDAP) that encourage more open routes, for example. These practices and fully open journals have been growing without badges (see here, here, here, here), sometimes at vastly higher rates than in PS.

It’s an open question, really, whether the spread of this badges brand will be a net gain or loss for open-ness in science. What if it spreads at the expense of more effective and open pathways? People who want to be open practitioners, but need to publish some things in high impact closed journals could do better for others by trying those that accept their work after it’s posted as a preprint with open data, rather than seeking out badges.

Here’s another from my personal badge collection. It’s pinned next to my computer at work. It’s an important one.

“Am I fired yet?” is one of several reminders to myself to put principles and public interest ahead of my personal interest. I learned, painfully, decades ago, that there is a strongly magnetic pull towards your personal interests. I learned it in advocacy movements. It’s not only commercial interest that’s a risk. You truly need to minimize bias in your approach to evidence, or you are lost.

As I’ve spent time with the badges “magic bullet” – simple! cheap! no side effects! dramatic benefits! – supported by a single uncontrolled study by an influential opinion leader, with a biased design in a narrow unrepresentative context, very small number of events, and short timeframe….I’ve come to think its biggest lesson may be that even many open science advocates have yet to fully absorb the implications of science’s reliability problems.

Continued on 31 August – FAQ with more data….What’s Open, What’s Data? What’s Proof, What’s Spin?

Follow-up post on 30 December 2019 – Open Badges Redux: A Few Years On, How’s the Evidence Looking?

[Update, 30 August 2017] Comment posted at PubMed Commons. [Update, 29 December 2019] PubMed Commons link updated with archived version at Hypothesis. The authors, although notified of this comment, never replied.

~~~~

Disclosures: My day job is with a public agency that maintains major literature and data repositories (National Center for Biotechnology Information at the National Library of Medicine/National Institutes of Health). I have had a long relationship with PLOS, including several years as an academic editor of PLOS Medicine, and serving in the human ethics advisory group of PLOS One, as well as blogging here at its Blog Network. I am a user of the Open Science Framework.

The cartoons and photo of badges (on my bag and wall at work) are my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

To start, I agree with the closing point. If there is one thing that I have learned from a career studying bias (https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=ztt_j28AAAAJ&hl=en&authuser=1) it is that everyone is biased, and the hardest biases to detect are our own. Dammit, two things. Two things I have learned.

The consequence of that in research is the requirement of open science to have any chance of detecting and mitigating biases that lead to false inference and slow down knowledge accumulation. In other words, acceptance of my own potential for bias is the primary reason that I preregister my research and make my data and materials available to others. It is the best opportunity I have to feel accountable when making decisions during research, and to be accountable to the evidence.

Context of the badges paper: In this paper, we knowlingly drew causal conclusions without a randomized trial (there was no random assignment to badges condition) and with the presence of possible confounding influences. More subtly, we both preregistered and included zero statistical inference tests – no t’s, F’s, chi-square’s, or p-values in the whole paper. In part, that’s just how we wrote the paper. But, it was also as an illustration of a more general perspective on making claims and evidence. No methodology guarantees unambiguous causal inference and no study is perfect. In all research, we are drawing inferences based on evidence and on plausibility assessments. Plausibility assessments consider what alternative explanations are possible AND their probability.

My core disagreement with Hilda’s assessment of the evidence is based on plausibility of the alternative explanations. Let’s consider what I think of as the main objections: (1) there were other changes in policies at the same time, and (2) the sample might have changed. Both of these are possible alternative explanations to our conclusion that badges caused an increase in open data. Are they plausible? I don’t think so for these reasons:

(1) Badges were introduced January 1, 2014 and authors were offered the possibility of receiving the badges on their article AFTER acceptance of the manuscript for publication.

— Like all journals, Psych Science has a publication lag. So, the first few months of publications in 2014 were mostly articles that had no opportunity to even apply for badges because they had already completed the publication process and were just awaiting placement in an issue (if memory serves, pub lag at Psych Sci flucutates between 3 and 6 months). But, more importantly than that, most (if not all) of the articles appearing in 2014 would have been *submitted* in 2013 prior to the policy going into effect. As such, for the first year at least, it is highly implausible that the policy would have affected decisions to submit.

— But, even after that lag, it is still implausible that the policy would have changed the sample deciding to submit because (a) the policy was not widely known (but became increasingly known), (b) the policy was applied after acceptance, (c) data sharing was optional, (d) few people in psych were sharing data in open repositories at all (baseline of the field was near zero everywhere, and (e) Psych Science is the premiere general empirical outlet in the field–not so easy to walk away from because you don’t like the fact that the journal asks if you’d like to share data after your paper is accepted. Even so, this could be tested more systematically by examining author characteristics pre/post badges to see if–for example–authors publishing after have a longer history of data sharing than authors publishing prior.

(2) The other policy changes were largely irrelevant to whether authors decide to share data. The presence of possible confounds does not address their plausibility. I assess the others as highly implausible influences on whether authors decide to share data compared to a mechanism of asking people if they would like to share data with a badge as credit for following the practice. [Moreover, the other initiatives are similar to changes pursued by other journals contemporaneously without any appreciable effect on data sharing, but that was not evidence in the paper.]

This comment is getting long enough, and I want to go to bed. So I leave the rest be except to note that, like any study, ours was neither definitive nor the final word. We consider it compelling evidence that badges are a simple, low cost incentive to improve data sharing with very little downside. And, it will be highly interesting to find out the extent to which the intervention’s effectiveness is generalizable to other domains. For example, I think it IS plausible that the high attention to reproducibility issues in psychology could serve as a primer so that any intervention to improve practices is more impactful as compared to a field that is not wrestling so publicly with reproducibility. Only with more research will we learn the replicability and generalizability of the findings of our first study. Now that 18 journals are offering badges and many more beginning to do so, I am eager to learn more about the effectiveness of the intervention, and other ways we might advance open science even more effectively.

The issue with badges is the same issue as with other ‘seals of approval’. Whenever one emerges, those with less than honourable intent will copy them and the average person is none the wiser – how should they know the difference between Badge A and equally officious-looking badges B-Z? This is science, not the boy scouts.

It will probably be less than a year before the usual predatory publisher suspects will have a simple tick box “Add open science / open materials badge to publication – $50” to their submission form. And no doubt our friends at Elsevier will take the hint and start charging extra for the ‘effort’ to include badges, which of course have to be Elsevier badges, not just any old badges.

The road to hell is paved with bad intentions and this is just another one – we can draw up all the guidelines and invent all the badges we want, but they won’t make a lot of difference unless GOOD PRACTICES ARE ENFORCED.

By all means we can do this badges thing; however I suggest the following:

A) A ‘p-hacked’ badge for papers with those… creative analytic strategies.

B) An ‘irreproducible’ badge for papers without data, materials, and vague methods sections.

C) A ‘surprise!!!’ badge for those randomised trials that were never registered.

D) A ‘power failure’ badge for trials claiming large effects from suspiciously low sample sizes

E) An ‘Infomercial’ badge for meta-analyses clearly designed to prove the authors’ pet theories/interventions

F) A ‘subverter’ badge for publications that willingly ignore reporting standards and guidelines

Thanks for the comment, Brian – and apologies for messing with your night with such a harsh assessment of this study.

That this study was preregistered, with open data, shows that as important as those things are – and I agree they are important and powerful – it’s by no means enough to counter bias in study design, execution, and reporting. Each can address very specific problems. But just like badges, they are not magic bullets.

Several decades ago, someone – unfortunately I forget who – in a critical appraisal training workshop I attended, said about bias in study design: “Bias is like meat in a lasagne. Once it’s baked in, you can’t get it out”. As someone who doesn’t eat meat, that’s a particularly powerful metaphor for me! You can’t get it out, but you sure can detect it. I think the argument “No methodology guarantees unambiguous causal inference and no study is perfect” is a cop out, Brian. You could, and should, have fully reported some of the major biases here for unsuspecting readers: to not even mention and reference in the article that there were co-interventions is a serious decision. That’s a basic level of transparency, to say the least. That you believe the co-interventions could not have influenced what you observed is irrelevant: you could have made that case in the discussion. Readers were entitled to know something this basic.

I agree that timing is an issue here. The editors’ announcement of the suite of interventions was in November 2013, and a chunk of the articles you included dated 2014 had already been e-published by then. It’s one of the reasons I used e-publication dates in my analysis. I also looked carefully at what happened for the year between the first data-sharing badge and the end of your study (and after it to see the impact of the short timeframe), to get my head around the absolute data that should have been reported in the paper to help people put this into perspective and be really clear on how small the numbers were. (I’ve now added that data to the Google sheet that goes with this blog post.) The numbers went up, then down, then up again. But what’s critical is to place them in context with the falling number of total articles.

You’ve reiterated your arguments as to why attracting more open authors can’t be a feature. That’s not taking into account how small the numbers are. Articles with you and other developers of the co-interventions as authors constitute a chunk of the articles getting badges. The numbers are so small, it doesn’t take many authors to affect them. But that is not my main point. The “natural selection” and impact of the co-interventions may be affecting the number of articles dropping – and that could be 2-sided. The major editorial changes that landed in January 2014 were intended to usher in more stringent requirements for accepting a manuscript for publication (thumbs up for that!). The very purpose was to reject weaker manuscripts. And if the total is anything to go by, they were either rejecting more or the editorial process stretched out longer as more revisions were required. And as of January (or November if they were aware of the editorial and associated buzz), authors could have been deterred from pressing the “submit” button. Your study has far too little data to begin to offer an adequate picture of what happened as a result of that suite of interventions: the journal wanted to increase open data and methods – and their commitment to that in various ways kicked in January 2014. I believe you should have reported the drop in journal productivity: you’ve just said again “very little downside”. If you are not open with investigating and reporting those downsides, how can anyone decide whether they think it’s “very little”? This has nothing to do with pre-registration or randomization. It’s akin to a drug manufacturer doing a clinical trial without measuring or reporting adverse effects.

I don’t know how, other than a major blind spot about things you are deeply invested in, to explain this.

How this got to publication in this shape isn’t only the authors’ responsibility of course: it’s not a preprint. This also raises questions about bias and adequacy of peer review at PLOS Biology. Due diligence by peer reviewers should have picked up on the big reporting holes here, especially given the red flags of spin. But just as you were concerned your comment was getting too long, I had to seriously cull the number of issues I addressed in my blog post. And just leave it at “open science advocates”. (Not, of course, that all open science advocates got on this bandwagon – I’m definitely not the only person who did not find this evidence convincing.)

Thanks – yes, I agree that badges are a risky business per se. I remember seeing a study in Germany (can’t think how to find it now), about badges for websites, where people were asked to report which ones they had seen and which they had trusted. And a badge that didn’t exist was in there. It was just as often seen and trusted in the survey as some that actually existed. So there’s that.

I would like to add a few other points to in these comments. Disclosure: I work at the Center for Open Science on the badging program, among other initiatives.

Bias is of course impossible to avoid. The study in question did include a preregistration in order to make some potentially biased decisions in a less biased way, before collecting the data. You can see the project materials here: https://osf.io/rfgdw/wiki/ including the preregistration here: https://osf.io/ipkea/

A recent systematic review (which we were not involved in conducting) found badges to be the only evidence-based incentive program that was effective at increasing the rates of data sharing: https://researchintegrityjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41073-017-0028-9 (I think the study authors decided that mandates are not included as an incentive, which I think aligns with the “carrot instead of stick” philosophy of encouraging ideal behaviors).

Thank you for raising the point that the path to the data is not open. We are investigating ways to make the data more discoverable and open. I think addressing the entire OA movement is beyond the scope of the badging program, but it is certainly a worthy ideal.

I’d also encourage you to peruse the more recent issues of Psychological Science. While we don’t have resources to do a follow up study at the moment, some eyeball statistics show that rates of open data sharing, materials sharing, and even preregistration continue to be quite high: http://journals.sagepub.com/loi/pssa

Finally, one philosophical point I’d like to make: A key benefit of the badging program is that it is effective at increasing ideal behaviors, more openness, without burdensome mandates that are more often than not conversation enders when discussing policy changes. If an author has any reason for not sharing data, no explanation or appeals process is needed, they simply do not ask for a badge. One of our recurring tactics is the cliche: not letting perfection be the enemy of the good. Your points will help to make the badging program better, just as the badging program has made data sharing more common.

Thanks, David. I’ve already addressed several of these points in my reply to Brian below, so I won’t repeat that here. Pre-registration etc can’t solve the problems of weak design.

You cited a systematic review to support the claim made in the Center for Open Science badges study, where the only study included in the systematic review is the Center for Open Science badges study. That doesn’t add any weight at all to anything – other than that this seems to be the only study. It doesn’t gain power, quality, or authority by virtue of being the sole study in a systematic review. (I’ll come back to that systematic review though when I get a chance – thanks!) It certainly does not make the practice of badges “evidence-based” – only strength of evidence can do that. And this evidence isn’t strong.

I did assess the recent issues: all the data in my post included recent data – and you’ll see in my reply to Brian that I added more of that data to the Google sheet. The numbers are still too small. (And I’m pleased that the transparency issues with the current method are being addressed – thanks!)

We disagree about what are potential major biases that needed to be featured and addressed in the discussion. I don’t discount the possibility that other variables could be biasing (as any observational study has countless variables that could be biasing). My assessment of the evidence is that they are not particularly plausible, just as we didn’t address turnover in the Editorial board, rise of other journals during the time frame, cultural context factors that focused on challenges at Psych Science in particular, etc, etc.

My discounting them doesn’t make me correct. You (or anyone) could advocate a position for how the other variables can account for the observed outcomes. And, some of the alternative scenarios are even testable with evidence. The most compelling possibility for testing changes in the sample is to actually evaluate the characteristics of authors pre/post intervention to examine systematic change.

Brian, none of that justifies not reporting co-interventions.

Good to know: I am a member of the badges committee (https://osf.io/tvyxz/), I am not an author of the article you discuss

Thanks for your clear analysis of potential problems with disentangling effects of open science incentives. Personally, I am not that interested in claims of specific intervention effects, nor do I believe it will be possible to disentangle them in any sensible way. This is not a controlled experiment, claims should be modest and in terms of correlation instead of causation.

That said, when the annus horribilis of 2011 hit our beloved science [Bem, Stapel], I was seriously considering leaving academia and it was the open science movement that made me change my mind, because the effects were clearly visible and a momentum was gaining that promised some real change.

I think it is not difficult to quantify that change, I also think that if you want to look for efficient causes, you can just as well point to the events of 2011, at least, that’s what got me here.

There are some qualitative, subjective reasons to support acknowledging open science practices by handing out badges:

– as a reader, I want to be able to quickly see wether open data and materials are available with a paper (and in the future hopefully also whether it has open, peer reviewed reproducible analysis scripts)

– as an author, I think it is a nice gesture to have the work that is involved in making data and materials accessible, acknowledged in some unambiguous way.

Therefore, I think your point 5 is the most serious problem we have to tackle. I do not want to see any badges acknowledging open data and materials on articles that are not openly accessible.

Anything you come up with to guarantee quality, can also be used to mimic/fake it, this holds for pre-registration, rigorous anonymous peer-review, high impact-factors, as well as handing out badges to acknowledge open practices.

As with any “stamp of approval”, whether it is the inclusion of “royal” in the name of a bakery, or getting a driver’s license, the actual proof of the pudding is eating it, get some mileage first, and if we feel we have to change the recipe because we are not reaching our intended goals, we should do so.

Thanks for the comment, Fred. You don’t need badges to show readers data is available: you can just prominently link to it, including metadata for the machines. For readers, you can show where the data is, Whether it’s data in something like GenBank, full data in simple studies totally contained within the paper, or data in supplementary materials that are open and easy to see.

The badge is not, of course, synonymous with compliance. Likely there will be badges meaning all sorts of different things: I think it will still be “reader beware”, as it becomes a marketing device. I agree the openwashing is serious: but so, I think, is promoting the idea that any of this is simple, and without costs. Nothing about what that journal did looked simple to me, or without cost to them and to authors. Effort needs to be made: encouraging people to choose a magic bullet that substitutes for effort doesn’t seem promising to me at all. Isn’t taking shortcuts a big part of what got us into this mess?

What are your goals and how are you going to measure whether you’re reaching them?

“The issue with badges is the same issue as with other ‘seals of approval’. Whenever one emerges, those with less than honourable intent will copy them and the average person is none the wiser – how should they know the difference between Badge A and equally officious-looking badges B-Z? This is science, not the boy scouts.”

“Thanks – yes, I agree that badges are a risky business per se. I remember seeing a study in Germany (can’t think how to find it now), about badges for websites, where people were asked to report which ones they had seen and which they had trusted. And a badge that didn’t exist was in there. It was just as often seen and trusted in the survey as some that actually existed. So there’s that”

I don’t agree with the sentiment of these quotes. If i am not mistaken, they way things are going now with the badges, all of them in use (open data, open materials, pre-registration) are being used when the paper provides actual links to this information to the reader. This means anyone who reads the paper can check whether 1) the badges are used correctly and 2) make use of the benefits of what the badges actually represent.

In my reasoning therefore, at this point in time there is no real danger of people abusing badges, nor do i see how they are a “risky business”. Sure, when journals start using other/their own criteria for handing out badges (i.e. hand out a pre-registration badge without providing a link to this information in the actual paper) then it could become a disaster, because the reader has to potentially “trust” the awarding party. This is always potentially dangerous, and in general can be considered to be anti-(open) science but is currently not the case with regard to the use of badges.

However, if i am not mistaken concerning open/good practices in general, it is unfortunately already the case that we have to “trust” certain practices without being able to check this for ourselves. For instance, concerning pre-registration with some Registered Reports (see Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology, i.e. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23743603.2016.1248079) i can’t find any link to the pre-registration information in the actual paper. If this is correct, and i am not missing something, this can be considered to be potentially dangerous and not in line with (open) science. If you want to talk about something being “a risky business” and the potential dangers of “seals of approval” i suggest you check out what’s happening there.

Altogether, this is why i think it is very important at this point in time to:

1) only use badges for practices/characteristics that can be checked by anyone who reads the paper, and

2) make this reasoning very clear to the community, and other readers in general, so there is a very strict line drawn concerning how to use/view badges (and open/good practices in general, i.c. concerning pre-registration).

This is fascinating stuff, very thought provoking. My first thought was that journals are mostly labels or badges anyway: an acceptance says “we have assessed this paper, and (to the best of our knowledge), it meets our journal’s criteria for content and quality”. One can only hope that these article-level badges are a stepping stone to journals adopting strict open data and reproducibility criteria and only accepting papers that meet them, so that appearing in journal X itself is a guarantor of open science.

My second thought was prompted by the discussion of whether a dataset can be truly open if the paper itself is not freely available. Since subscription journals are going to be around a lot longer than unavailable data, it’s worth thinking how to address this in the short term. Perhaps journals should always make the methods and results publicly visible, and hold the introduction and discussion behind the paywall?

Thanks for your critique, Hilda. I do feel a need to point out that open data and open materials, without open access to the article itself, are not going to do much good. There are usually things in the article that you need to know in order to correctly interpret the data and materials. I agree that too much weight is being put on the single term “open” — perhaps we should talk about “published” data and materials instead?

“I do feel a need to point out that open data and open materials, without open access to the article itself, are not going to do much good. There are usually things in the article that you need to know in order to correctly interpret the data and materials”

I agree. Although it can’t hurt for journals to provide access to open data, open materials, and pre-registration information in some way or form when they hand out badges without providing access to the actual paper, i reason that would not make much sense.

I see open access and open practices as two different things.

You don’t need badges to be able to see if data is available or make use of the benefits, though, do you? The badge is redundant for that. As currently operationalized, there is no link when you click on the badge itself anyway, so it’s a moot point.

Of course people can start putting on badges and making claims for their badges – and it would be surprising if they didn’t, if badges come to be seen as a successful marketing device. The same thing occurs with the use of the label “open access”. Or, as I showed in this post, the use of the open access symbol when you are past a paywall. Entire scam journals are created these days, and that’s a much more intensive thing to do than whipping up a badge. There is a major problem here, in the portrayal of slapping on a badge as “simple” and “low cost”: done properly, it is not all that simple, especially where the data aren’t even necessarily under the journal’s control and could be removed/disappear. Given the badges don’t signify open-ness of all the data – although all of it might be there, it’s not required – and some of it has already disappeared, the badges are definitely “reader beware”, I agree. (See alo my follow-up post)

Thanks, Tim. Check out my follow-up blog post too – it turns out there is another study that sheds some extra light.

Yes, the rationale for this is as a stepping stone, although I think the marketing of them as “simple” and “low cost” may be encouraging the opposite. It’s providing an “out” for journals too: they and authors can market pride about open data, even when that data is only very partially open.

Richard Smith comes to mind in particular as someone who has advocated that the future of journals is discussion about research, not publishing the research itself. I think that’s probably true. There’s another model, at journals like Richard’s old stomping ground, the BMJ: all research articles free to view at least, and only opinion articles, news, etc behind the paywall.

The thing about making methods and results visible is that it’s very hard to make sure that no substance whatsoever only appears in the discussion. Discussion often has explanations of what was done, for example, in discussing limitations. As a systematic reviewer, you really need access to all the study’s artifacts. The paper is part of the study, and thus, the paper itself is data. If I want to assess the reliability of a study, seeing the introduction – which generally includes the study rationale – matters, too. What if, as often happens, the entire thing is predicated on something that has itself been discredited? How would I know, if I couldn’t see it?

I agree, Roger, but “published” doesn’t help: published behind a paywall is such a deterrent to readers, that it might not as well not be published from their point of view. It’s too late, I think, to change the word “open” for this. And even if we did, the next word would be abused too. Anything that has marketing potential would be.

“You don’t need badges to be able to see if data is available or make use of the benefits, though, do you? The badge is redundant for that. As currently operationalized, there is no link when you click on the badge itself anyway, so it’s a moot point.”

Thank you for the reply!

I agree more with the poster above when he said the following:

– as a reader, I want to be able to quickly see wether open data and materials are available with a paper (and in the future hopefully also whether it has open, peer reviewed reproducible analysis scripts)

– as an author, I think it is a nice gesture to have the work that is involved in making data and materials accessible, acknowledged in some unambiguous way.

To me, these things are the main function of the badges. And with that in mind they are not redundant in my reasoning. They clearly signal open/good practices over and above links in the paper, which could also be helpful in promoting, and possibly, rewarding these practices (i am hereby assuming all use of badges comes with the prerequisite of actually including links in the paper to the information the badge represents as is still the case thus far if i am not mistaken).

Seems like a variant on the badges might be to have a compact list and rating from the publisher, fashioned after Roche and others’ evaluation. For instance –

_Data Completeness: Exemplary. All the data necessary to reproduce the analyses and results are

archived. There is informative metadata with a legend detailing column headers, abbreviations, and units.

_Data Reusability: Exemplary. The data are archived in a nonproprietary, human- and machine-readable file format and raw data are presented.

This does beg the question, who is to evaluate the completeness and reusability of data? The Editor? It hard enough to make time to review manuscripts. Still, if nothing else the increased attention to data openness has to be a good thing. Badges can be counterfeit or not meaningful to all* and any criteria can be gamed, such as conflict disclosures or authorship rules, and all authors and papers are above average.

*Remember “Badges? We don’t need no stinkin’ badges.”?

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002295

Sure, badges aren’t magic bullets. They were never designed to be. They are one potential tool, amongst many that open-science advocates are pushing. Nobody thinks that this has solved all the problems in scientific integrity. I don’t think anyone’s advocating that now we’ve got badges we should stop caring about open access journals, or improving statistical rigor and training. There are a million ways to cheat and introduce bias and, for sure, badges don’t prevent that.

But if the badges even slightly increase people’s willingness to share their materials (and I agree that it’s early days to tell that) then they are good for science. Not just from a reproducibility perspective, but for accelerating scientific progress by providing teaching tools and scaffolding.

Sure, the data on how much these have helped are sparse at the moment, but I don’t think it’s time to complain that the badges aren’t a “magic bullet”.

(FYI: I’m also on the Badges committee, indeed I originally proposed their creation, but I have no vested interest or personal benefit from them and was not an author of either of the manuscripts).

Thanks for your comment, Jon. My point is not to complain that they are not a magic bullet. My point is that they are promoted as though as they are: “simple”, “low cost”, “dramatically” “effective”. That’s not just in this article – it’s become widespread, fueled by this marketing claim. Weak science with exaggerated claims is part of the problem: modeling or condoning more of it isn’t going to accelerate scientific progress.

“I work at the Center for Open Science on the badging program, among other initiatives. ”

I read you are also part of “Registered Reports” and that you and the Center for Open Science are all about transparency and all that good stuff.

I don’t understand several things about “Registered Reports” though, which i hope you are willing and able to make clear. For instance, how do “Registered Reports” fit with transparency, as i can’t seem to find any pre-registration information in published “Registered Reports”.

What does “registered” mean/imply exactly in “Registered Reports”?

Possibly interesting and important thread about Registered Reports and “open” science in general, which provides some answers, can be found in the comment section here (also includes a link to this blog post):

http://andrewgelman.com/2017/09/08/much-backscratching-happy-talk-junk-science-gets-share-reputation-respected-universities/

I would like to add, and ask, a few things regarding this whole thing:

1) I am not a fan of people or institutions investigating and evaluating their own proposed “improvements”. It’s like the saying “marking your own homework” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marking_your_own_homework).

Nosek (and/or the “Center for Open Science”) wrote he created the badges, and is part of the “badges committee” in the 2016 badges-evaluation paper (but also see the comment by Jon Peirce above), and is the director of the “Center for Open Science” that gets millions to try and “improve science”. He is also one of the 2016 badges evaluation paper authors. I think this is all a huge conflict of interest, and not very wise. and not scientifically sound.

2) Am i understanding things correctly here that they only included 2 of the 3 available badges in the Kidwell et al. (2016) badges evaluation paper?! They seem to have left out investigating the pre-registration (and/or pre-registration + analysis plan) badge. Why is that? Is this a case of, or similar to, “selective reporting” ?

3) The “TOP-guidelines” (Transparency and Openness Promotion) were mentioned in a 2015 paper, which is prior to the 2016 paper that “evaluated” the open practices badges. The “TOP-guidelines”, signed by thousands of journals, explicitly mentions, and includes, use of the open practices badges.

For instance, at page 20 (https://osf.io/ud578/) it is mentioned that at the highest level (level 3) of “Transparency and Openness”: “The journal, or an entity acting on behalf of the journal, will verify that the preregistration adheres to the specifications for preregistration and then provides certification [the word “certification” is hyperlinked and leads to the site about the badges] of the preregistration in the article”

Am i understanding things correctly here that the Nosek (and/or the “Center for Open Science”) came up and promoted the badges, which they incorporated in the “TOP-guidelines” (which he/they also came up with) without any solid evidence that the badges are even a “good thing” for (improving) science?

4) Am i understanding things correctly that the “TOP-guidelines” at the highest, supposedly most “open” and “transparent” level 3, does not even seem to (explicitly) mention that, for instance, the “pre-registration” should be made available to the reader by a simple link in the paper?

5) Am i understanding things correctly here that the “TOP-guidelines” at the highest, supposedly most “open” and “transparent” level 3, talks about the possibility of a 3rd party that could “verify on behalf of the journal” whether the badges are handed out correctly?

6) Combining 4) and 5), am i understanding things correctly here that the “TOP-guidelines” could at the highest, supposedly most “open” and “transparent” level 3, therefore involve the “Center for Open Science” itself acting, on behalf of the journals, as the “verifying 3rd party” that will make sure the badges are “handed out correctly”? (and could they then perhaps even totally leave out any links in the actual papers so the reader isn’t actually able to verify things themselves?)

7) Is this all pretty bad science, and/or a giant conflict of interest?

Relevant to the discussion might be the following recent paper by Rowhani-Farid & Barnett (2017) “Badges for sharing data and code at Biostatistics: An observational study”:

https://f1000research.com/articles/7-90/v2

Two quotes from the paper:

“Badges for reproducible research were not an innovative creation of COS however. The journal Biostatistics introduced badges, or what they called kitemarks (named after the UK kitemark system of establishing product safety), on 1 July 2009 as part of their policy to reward reproducible research. The policy was introduced by Roger Peng, the then Associate Editor for reproducibility (AER)”

“The effect of badges at Biostatistics was a 7.6% increase in the data sharing rate, 5 times less than the effect of badges at Psychological Science. Though badges at Biostatistics did not impact code sharing, and had a moderate effect on data sharing, badges are an interesting step that journals are taking to incentivise and promote reproducible research.”

“5) Am i understanding things correctly here that the “TOP-guidelines” at the highest, supposedly most “open” and “transparent” level 3, talks about the possibility of a 3rd party that could “verify on behalf of the journal” whether the badges are handed out correctly? ”

I just re-read the following thread (that i started myself), where it seems that the “Center for Open Science” (COS) is (or should i say was?) actually planning to find 3rd party -issuers for the badges if i understood things correctly (see post by Mellor on 24-01-17):

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/openscienceframework/7oeul9pusKg

Am i understanding things correctly here that after years of talk about how things like peer-reviewers, journals, and editors messed things up in science (due to money, influence, etc.), they now want to create even more entities and barriers that can be abused and manipulated in the form of some 3rd party that “verifies” whether the badges are handed out correctly? How is this “open science”, when it seems to me that all of this would involve putting up more barriers and hoops to jump through?

I am starting to wonder whether the “Center for Open Science” (COS) could (should?) actually be called “Controllers of Science” (COS), because that seems to me to be more in line with a lot of their efforts thusfar…

Also see Binswanger “Excellence by nonsense” paper in this regard:

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-00026-8_3