Network meta-analysis (NMA) is an extension of meta-analysis, combining trial evidence for more than 2 treatments or other interventions. This type of…

Building a Great Scientific Abstract: A Quick Checklist

It should never be a rushed afterthought. An awful lot is riding on the quality of scientific abstracts. Most readers will rely on that summary, delving in no further. And a conference abstract, including the title, will determine whether a poster or talk is accepted – and whether some people come to it.

Despite their importance, abstracts tend to be infested with problems. Important craft elements are missing, and many are riddled with scientific problems. I wrote about that and related studies in an earlier post for readers, Science in the Abstract: Don’t Judge a Study by its Cover. This follow-up post is for scientists writing abstracts: it’s my top 6 generic tips on getting the content right.

Before we start: there are reporting guidelines for abstracts of several research types, like clinical trials. The EQUATOR Network gathers those for health studies, so check here to see more specific recommendations. Other reporting guidelines can also have at least some mention of abstracts, so they are always worth checking. (Disclosure: I’m one of the authors of the reporting guidelines for abstracts of systematic reviews. Following reporting guidelines can improve abstracts, although issuing detailed instructions hasn’t always been shown to help.)

Let’s start with the basic structure.

1. Structure to cover key bases, even if the journal style doesn’t have subheadings.

In health and some other areas, structured abstracts were introduced at journals in the 1980s. There’s no standard here, but it involves breaking the abstract up into sections with subheadings like “Background”, “Methods”, and “Results”. It’s common for conference abstracts to be structured, too.

James Hartley points out that there’s not a lot of research to help on this, and it has serious limitations. He concludes, though, that it suggests that structured abstracts

Even if the journal doesn’t have a formal structure to follow, it’s logical to follow a model like that – even without the headings – to make sure you cover the basics of why the study was needed and how it was done, as well as what was found.

Be careful on the background “why”, though: use the space for more on “how” and “what” was done. Pet hate: background sections that say something like “There is no study that….”, while reporting a study that does! Put in a bit more effort: there is no room for “fillers” in this prime real estate.

2. Include the methodology in the title – and clear signals for the research stage are good, too.

As with structured abstracts, you can hit journal policy issues here. But from a user point of view, knowing as soon as possible what kind of study it is is helpful. In particular, if it’s a study protocol, it should say so.

If the paper is reporting the protocol stage of research, it’s particularly helpful to have that in the title so people know there are no results without investing time.

The converse is true for results – especially for conference abstracts. When a conference is accepting abstracts for incomplete projects, signaling that you have results can help let prospective attendees know that directly in the conference program. By “signal” here I mean something like including numbers of participants.

3. Write to be found by those who want to read your report.

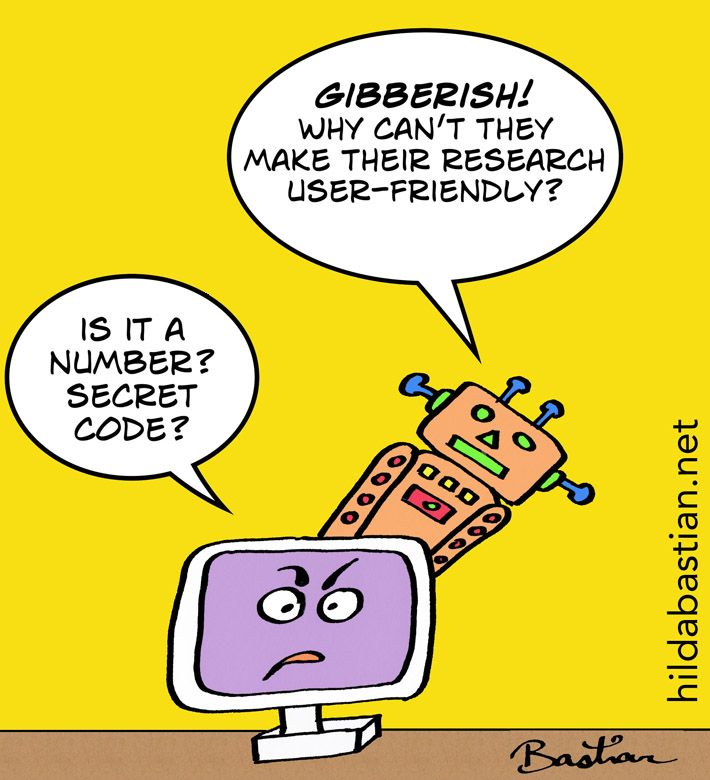

Remember that you are writing for humans – but also for search engines and researchers using algorithms and machine-assisted learning to identify studies.

The key outcome here is not to be overlooked by the people or “machines” that might be interested in your work – but not to waste the time of those who really aren’t.

If you’ve got the methodology in the title, you’re already one step ahead here. Key words in the title have more weight than those in the body of the text, or allocated key words. But they all count. An information specialist can help you here. (Ask your librarians!) And think about how you find the articles you’re interested in.

4. Make sure there is nothing in the abstract that isn’t covered in the main article – or that contradicts it.

This is an extremely important last check you have to do at the end – no matter how sick you are of the manuscript after peer review! Inconsistencies between the abstract and main text are very common. In my previous post, I cite studies that show from 18% to 68% of abstracts studied contained inaccuracies or other problems.

Ideally, everyone does this one last check – but make sure you and at least one other person does it, carefully.

5. Scour your abstract to remove any spin that has crept in along the way.

Academic spin is common in abstracts – people go too far trying to get people to read their work. One study, for example, found that 84% of 128 articles contained some form of spin in the abstract. But it’s bad science.

Check your abstract carefully to make sure you’ve included the most important outcomes you planned at the beginning of the study, not a cherry-picking of the most impressive. This exercise isn’t about accentuating the positive: that can mislead people.

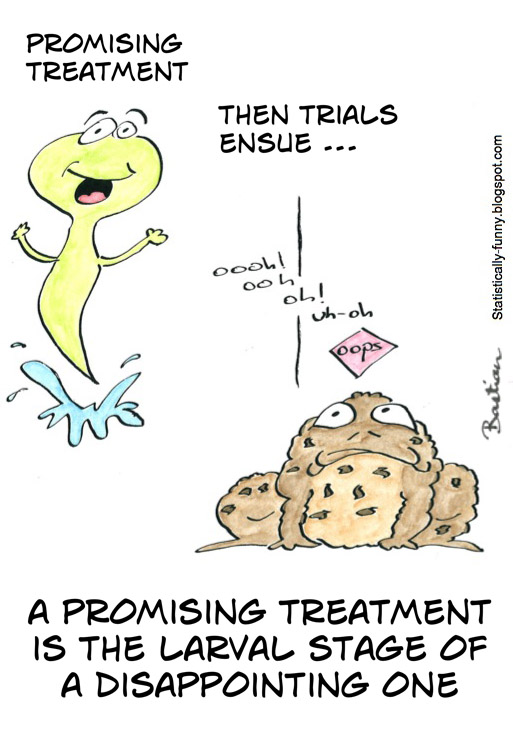

What are looking to purge? Things that exaggerate your study’s findings or importance in any way. It could be over-representation of “statistically significant” or otherwise selectively positive results. It could be leaving out bad news (like adverse effect data). Or it could be language – words like “promising” and “novel” are danger signs. You want neutrality and objectivity: adjectives and adverbs – any superlatives – are risky.

6. Include any identifier, like a registry number.

Your study may have important identifiers, like a clinical trial registry number. The journal may incorporate this separately, hard-coded in. Check their other articles and information for authors. Otherwise, make sure you include it in the abstract. I’ve written more about this here, in a post on the importance of being a machine-friendly researcher.

If you have gone through the process of formally screening abstracts for systematic reviews, or some other form of meta-research, you know just how hard it can be to divine even the most basic critical bits of information about studies. It’s astonishing how often you can’t even tell how many research participants or subjects there were – and of what species!

If there are reporting guidelines for the type of study you writing up, you are in luck. If there aren’t, then you can sort of reverse engineer the process by looking at quality assessment tools or meta-research on studies in the area to see what signals you need to be sending, from the title and abstract onwards. Don’t think of it as either a chore, or an opportunity to put a sheen on results. Polishing your abstract should be your victory lap for a study that was well done.

If you’re looking for guidance on writing, here’s an LSE post geared towards the social sciences with generally useful pointers. Several blogs on academic writing are recommended here, including Explorations of Style and the LSE Blog, Writing for Research.

~~~~

The cartoons are my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

1, “Why” part shall creep no space in abstract. The work is by default (!!) worth the research time and ingenuity of the author(s), ain’t it?

2, “Major Finding” is a must, and shall preferably the lead sentence of the abstract.