It’s a Start: The Amended Version of the Cochrane Review on Exercise and CFS

It’s tough, watching this play out slowly, step by painful step. As I’ve blogged before, ME/CFS consumer advocates have been hammering away to get this Cochrane systematic review on exercise and CFS fundamentally changed since 2015. I think they’re right. And now, they have achieved something pretty remarkable…

Kudos to Robert Courtney (now deceased), who got this ball rolling, and those who picked up the baton, especially Tom Kindlon and George Faulkner. But why do I think it’s only a start?

Firstly, I need to disclose that I’ve been directly involved in recent negotiations around the fate of this review, although I didn’t see this version till after it was published. The organization released a statement along with the amended review, making it clear that this is only a first step. Karla Soares-Weiser, the new editor-in-chief, said:

“We have decided, therefore, that a new approach to the publication of evidence in this area is needed; and, today we are committing to the production of a full update of this Cochrane Review, beginning with a comprehensive review of the protocol, which will be developed in consultation with an independent advisory group that we intend to convene. This group will involve partners from patient-advocacy groups from different parts of the world who will help us to embed a patient-focused, contemporary perspective on the review question, methods and findings.”

That is such good news.

In the meantime, what has changed with this amendment, and what hasn’t?

First up, why it merits the “changed conclusions” tag. (Here’s the new version, and here’s the previous one.)

The key bit of the old conclusion:

Patients with CFS may generally benefit and feel less fatigued following exercise therapy, and no evidence suggests that exercise therapy may worsen outcomes.

The key bits of the new conclusion:

Exercise therapy probably has a positive effect on fatigue in adults with CFS compared to usual care or passive therapies. The evidence regarding adverse effects is uncertain… All studies were conducted with outpatients diagnosed with 1994 criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Oxford criteria, or both. Patients diagnosed using other criteria may experience different effects.

What’s good about this is opening the door at least to the possibility that exercise therapy can do harm. And it opens the door to the question of just who the research reviewed applies to. Let’s go to what the other major systematic review on the question concluded, in 2014, the same year as the Cochrane review being amended now. It’s from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

None of the current diagnostic methods have been adequately tested to identify patients with ME/CFS when diagnostic uncertainty exists.

Then, in 2016, after an NIH meeting agreed with them:

[U]sing the Oxford case definition results in a high risk of including patients who may have an alternate fatiguing illness or whose illness resolves spontaneously with time… The National Institute of Health (NIH) panel assembled to review evidence presented at the NIH Pathways to Prevention Workshop agreed with our recommendation, stating that the continued use of the Oxford (Sharpe, 1991) case definition “may impair progress and cause harm.”

Blatantly missing from this body of literature are trials evaluating effectiveness of interventions in the treatment of individuals meeting case definitions for ME or ME/CFS.

So we’re talking about a body of evidence that may apply to some degree to people who don’t really have ME/CFS or CFS.

Before we move on, the existence of such important voices as AHRQ and the NIH contradicting the Cochrane review is a Very Big Deal. This is what the amended Cochrane review still says on that score, though:

[T]he results reported here correspond well with those of other systematic reviews (Bagnall 2002; Larun 2011; Prins 2006) and with existing guidelines (NICE 2007). One meta‐analysis of CBT and graded exercise therapy (Castell 2011), suggests that the two treatments are equally efficacious, especially for people with co‐morbid anxiety or depressive symptoms… The conclusions presented in our review correspond well with those of other relevant studies and reviews.

I argued strongly that this shouldn’t be allowed to stand. Yet, there it remains. And now it’s definitely cherry-picking.

Cherry-picking sounds kind of innocuous, doesn’t it? Phrased as it is in that last sentence, though, it’s anything but. (To go full Aussie for a moment: Not happy, Jan!)

Back to what has changed, though – and all of the changes are, I think, changes for the better. From Cochrane’s statement:

It now places more emphasis on the limited applicability of the evidence to definitions of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) used in the included studies, the long-term effects of exercise on symptoms of fatigue, and acknowledges the limitations of the evidence about harms that may occur.

We’ve looked at the first and last of these. Here’s what happened about the long-term effects on symptoms of fatigue. Firstly, the absence of long-term effects is now liberally sprinkled through the abstract, where there was no such mention before.

Secondly, the closest the summary of findings table used to get to this was saying there was moderate certainty from 3 studies that exercise therapy lowered fatigue at the end of treatment. Now, the results of 4 studies with longterm results are included, for fatigue and some other outcomes, with “very low” certainty, for example:

The effect of exercise therapy on fatigue after 52-70 weeks is uncertain.

And the effect there is dependent on a single study that drags lots of the meta-analyses towards more apparent benefit, Powell 2001 – in the context of one discussion, they are referred to as “deviating results”. There are more sensitivity analyses now – that’s weighing the impact on results of excluding one or more studies.

The “What’s New” table of the review also points to change in the fatigue analyses, “restructuring the analysis of fatigue to combine data with standardised mean differences”, as opposed to simply mean differences in the original. (My explainer on that here). And that makes a serious difference. For example, Analysis 1.2, fatigue at follow-up, now touches the line – so not statistically significant any more. (My explainer on data in meta-analyses is here.) The result here was affected by dramatic between-study differences (an I2 of 94%, which is pretty much off the charts – see my explainer). That was almost halved by removing the Powell study again, and that also reduced the apparent benefit even more. Don’t forget, though, that this is old data: there are more studies now, so it all feels a bit moot.

The previous editor-in-chief, David Tovey, had originally proposed that the review be withdrawn as it was so out of date, but that wasn’t well received, and it didn’t happen. Looking at it today, with all the statements in there that look current – like saying this version has had trials added – withdrawing it back then seems reasonable, and consistent with Cochrane’s practice, and its policy at the time (section 3.4.7 here). Not withdrawing it then seems political.

In July 2019, though, there was a new policy on withdrawing reviews, making it more clearly a retraction than it used to be, making it much less of an option. An updated review isn’t going to be galloping over the horizon any time soon, though. I think this review now highlights a gap in Cochrane policy: there isn’t currently a mechanism for unambiguously and clearly flagging a review as out of date to readers. There’s just an editorial note where few would see it stating that it’s “substantially out of date”.

This review over-estimated the strength of the evidence and its applicability, and while better, it’s still doing that. That has been having a damaging effect on people to whom the results don’t apply, but on whom the consequences of this review are visited. Yet, until Courtney’s complaint got Tovey involved, consumers had been resolutely locked out of this Cochrane review, and indeed, this amendment process too. That was against Cochrane’s stated ethos. It’s great that Soares-Weiser is going to rectify that. Consumer participation isn’t only for when it’s smooth sailing. When it’s going to rock the boat may be the most important time of all to do it.

Consumer group takes on the amended review have started to appear:

- Emerge Australia

- ME Action

- ME Association (medical adviser)

~~~~

[Update 4 October 2019] In responding to an enquiry from a consumer group about Cochrane policy on withdrawing reviews, I found that there was a new policy in July 2019. And a new version of the Cochrane Handbook was published this week. That means part of my original post was wrong. The original read:

The previous editor-in-chief, David Tovey, had originally proposed that the review be withdrawn, but that wasn’t well received, and it didn’t happen. An editorial note on the review points out that it is “substantially out of date”. Once that determination has been made, Cochrane reviews are supposed to be either updated or withdrawn. It’s now nearly a year since then, and a replacement review isn’t going to be galloping over the horizon any time soon. Looking at it today, with all the statements in there that look current – like saying this version has had trials added – withdrawing it seems reasonable, and not withdrawing it seems political.

Disclosures: I have had discussions with The Cochrane Library’s Editor-in-Chief, about this review, and participated in a discussion with the Cochrane Editorial Unit and others about it. I did not discuss the contents of this post with anyone before posting.

I was a health consumer advocate (aka patient advocate) from 1983 to 2003, including chairing the Consumers’ Health Forum of Australia (CHF) from 1997 to 2001, and its Taskforce on Consumer Rights from 1991 to 2001. I have not experienced CFS/ME and nor has anyone close to me.

However, at the time I first encountered CFS activists, I had a relevant personal frame of reference. I had to leave my occupation several years prior after a severe bout of repetitive strain injury (RSI) following a stretch of workaholism as a teenager. Then, RSI was regarded by some medical practitioners as malingering or psychological, rather than a physical condition. (You can read about the controversy around Australia’s RSI epidemic here, here, and here [PDF].)

As then editor-in-chief of a consumer health information website based on systematic reviews at the NIH, I was pressured about the inclusion of systematic reviews on GET and CBT and approach to CFS consumer information, but not by CFS activists.

I was the consumer representative from the foundation of the Cochrane Collaboration in 1993, and leader of Cochrane’s Consumer Network from its formal registration in 1995 to 2003. I was the coordinating editor of a Cochrane review group from 1997 to 2001.

One of the authors of the planned Cochrane individual patient data review, the protocol of which was withdrawn, is my PhD supervisor, Paul Glasziou. We have not discussed it, and have not discussed anything related to this post while I was considering, researching, and writing it. We have not discussed the previous post either.

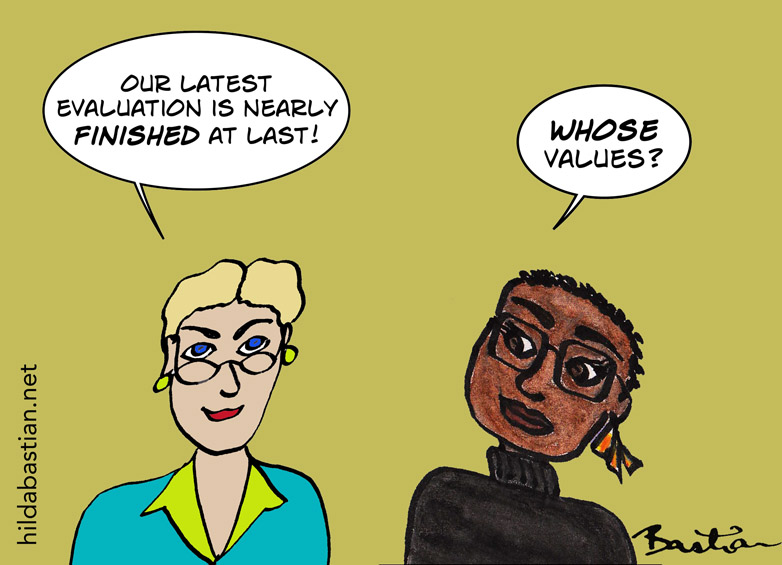

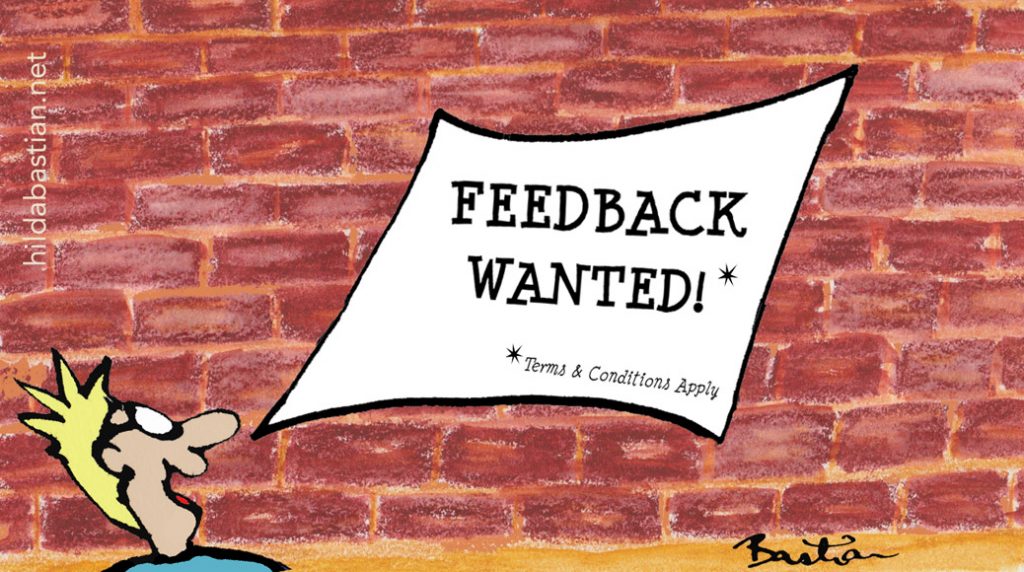

The cartoons are my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

I don’t think the updated review is much of an improvement. It is marginally better, but still relies on a body of evidence that is so weak and biased as to be uninterpretable. Moreover, the selection criteria explicitly state a reliance on RCTs, while the biggest piece of evidence used, the PACE trial, is not a controlled trial. Most of the other trials are not controlled either while some aren’t even properly randomized, as demonstrated by Vink and Vink-Niese. It is hard to explain such a blatant deviation at the starting line.

Those changes are unlikely to have any impact on patients, the differences are so minute that only people who pay close attention to the issue will even be able to tell what actually changed. I think you expressed it best here in saying:

“So we’re talking about a body of evidence that may apply to some degree to people who don’t really have ME/CFS or CFS.”

We know for a fact that several trials involved had many participants who do not fit any of the reliable criteria for ME, in some cases, as is with PACE, to an even larger proportion than the meager reported benefits. Even then, the evidence for those other patients remain weak and fraught with manipulation. Research using Oxford criteria, as is PACE, should be retracted and dismissed as unreliable, they are simply unfit for purpose.

Most physicians are simply not aware of the reality of this disease, do not even know there is such a thing as very severe ME patients, who cannot even feed themselves or communicate with others. The vast majority of medical professionals reading this review will not know to make this important distinction, leading them to give the same old misleading harmful advice to their patients.

Exertion is used by genuine researchers in the field to induce symptoms and study their effect. Exertion is, in fact, a precipitating factor in deterioration. To recommend a precipitating factor of deterioration as a valid treatment, one that has been promoted as a complete cure by the people involved in the research supporting this school of thought, remains malpractice and irresponsible.

The note from the editor-in-chief is positive, but undercut by the review itself. None of the authors involved are credible experts on the topic, in fact are highly biased actors within a small ideological circle. The promise of working with patient organizations is the only truly positive commitment, but there will need to be absolute, almost exaggerated, transparency in the process. The process used in this review has been completely opaque and will not be acceptable.

In caving to political pressure and refusing to retract an obviously flawed piece of misleading evidence, Cochrane’s goodwill, and competence I might add, remains very much in doubt. Sometimes it takes a particular knowledge about a topic to be able to appreciate expertise, especially its absence.

Unfortunately not much actual expertise was involved in the making of this newly amended review, a small fractional change from the early 2004 one, every bit as misleading and harmful to the welfare of patients. It is unfortunate but clear that Cochrane has sided against patients’ interests here, moving the needle as little as possible without taking much consideration to contradictory evidence, especially that of the reality of a human rights disaster in implementation, as those treatments have been used in practice for decades and have been demonstrated to be harmful at worst, useless at best.

The psychosomatic paradigm built on CBT and GET has been a complete and total failure in practice. Decades of work by hundreds of researchers spending millions on dubious research and misleading services have amounted to an unfortunate grade of zero, failure beyond any reasonable claim to competence and goodwill. In fact, a good starting point for the future would be to use the current paradigm as exactly the worst possible outcome and build from its complete opposite.

I thank you for your continued interest, it is rare and inspiring. I just fear that the reality for millions of patients will not change anytime soon, as most physicians do not have the time and energy to spend beyond which recommendations stand, and for now exercise remains the standard, though of low evidence, despite its use in research as a trigger for illness and consistent failure in patient surveys.

The only truly positive move will be for Cochrane to not only retract this entire review, as well as its companion for CBT, but also investigate how such misleading, unevidenced recommendations from biased and conflicted researchers made it to publication in the first place. Only then may some trust be repaired with the beneficiaries of Cochrane’s work product: the patients. For now we continue to take a back seat to politics and ideology, deprived of informed consent and our testimony unheard.

To what extent do you agree with the following summary?

1. ME/CFS is vaguely defined and probably very heterogeneous. Its diagnosis is therefore arbitrary.

2. Nobody has the slightest idea about what causes it.

3. There are no very effective treatments.

Pretty much all of those. The lack of basic knowledge doesn’t seem to inhibit many people from being totally confident they know what’s best, though, unfortunately.

As an ME patient, I would say:

1. ME/CFS is probably heterogeneous, but that doesn’t mean that the diagnosis is arbitrary. It means that it is probably heterogeneous. There are different diagnostic criteria, some of which are more useful than others, and within those criteria there are likely to be different sub-groups and probably different illnesses. However, that doesn’t mean that the diagnosis isn’t useful. The recognition that there are significant numbers of people who are disabled by illness who meet specific diagnostic criteria (particularly post-exertional malaise, or PEM) is important and necessary for advocacy and research. Having said that, I also strongly agree with the NIH panel which concluded that “the continued use of the Oxford (Sharpe, 1991) case definition may impair progress and cause harm” (as quoted by Hilda above).

2. A bit like CFS, “cause” seems to be a heterogeneous term used to mean different things. There appear to be a number of triggers for ME/CFS, such as EBV, but knowing the triggers is less important than understanding the mechanism, identifying biomarkers, and developing effective treatments. There has been some limited progress made in identifying potential biomarkers (see, for example, this blog on evidence of “something in the blood”: https://mecfsresearchreview.me/2019/12/10/latest-from-ron-davis-more-evidence-of-something-in-the-blood/) and hypothesising about possible mechanisms but there is still a very long way to go.

Unfortunately, the PACE trial and Cochrane reviews, along with the “collective ad hominem attack” on the ME community by a small group of influential researchers (referred to in Hilda’s previous blog: https://blogs.plos.org/absolutely-maybe/2019/02/08/consumer-contested-evidence-why-the-me-cfs-exercise-dispute-matters-so-much/) appear to have had a significant effect on inhibiting progress by perpetuating the myth that ME/CFS can be reversed by CBT/GET.

3. Agreed. Moreover, the FINE and PACE trials provide good evidence that CBT/GET are ineffective treatments for ME/CFS, even when using very broad and diagnostic criteria.

Thanks for taking an interest in this, David. And many thanks to Hilda for your blogs and ongoing efforts to try to help to resolve the issues which have been so harmful to ME patients.