Decision-making about drugs in pregnancy can be very difficult. Our illogical aversion to clinical trials in pregnancy means people making particularly complex…

Science Populism, Medicine Style

I hadn’t been aware of the term science populism until a video about it did the rounds recently. It was a light-bulb moment! This concept helps make sense of the relationship between a wing of the evidence-based medicine movement and anti-science politics. Other categorizations like contrarianism, anti-industry bias, and “medical conservatism” apply to the influencers I mean, but didn’t fully account for why they would slot so seamlessly into right-wing media ecosystems and regimes.

The video, entitled The Rise of the Science Populists, is by particle physicist Sam Gregson. It’s no coincidence that science populists become darlings of populist political movements, argues Gregson—intentionally or not, the relationship is symbiotic because of some shared beliefs and approaches.

Populism is “a world-view that divides the polity into a pure people and a corrupt elite, shrugs off the trappings of liberal democracy as a ruse of that elite, and prefers a nationalist, authoritarian politics driven by hostility to minorities and to pluralism in general.” It’s that superior us, versus a contemptible them, that signifies both political and science populism. As Gregson puts it, science populists “lean into the same distrust of experts and institutions that powers popular political movements around the world.”

These influencers, he says, are “selling to audiences the sense that they are privy to hidden knowledge—hidden knowledge which experts dismiss, fear, or do not even understand…[They] are marked by their cynicism, and spend a significant fraction of their online airtime spreading mistrust of science and scientists, suggesting that the scientific enterprise is under-delivering for the public, undermining the scientific consensus while championing popular contrarian viewpoints.”

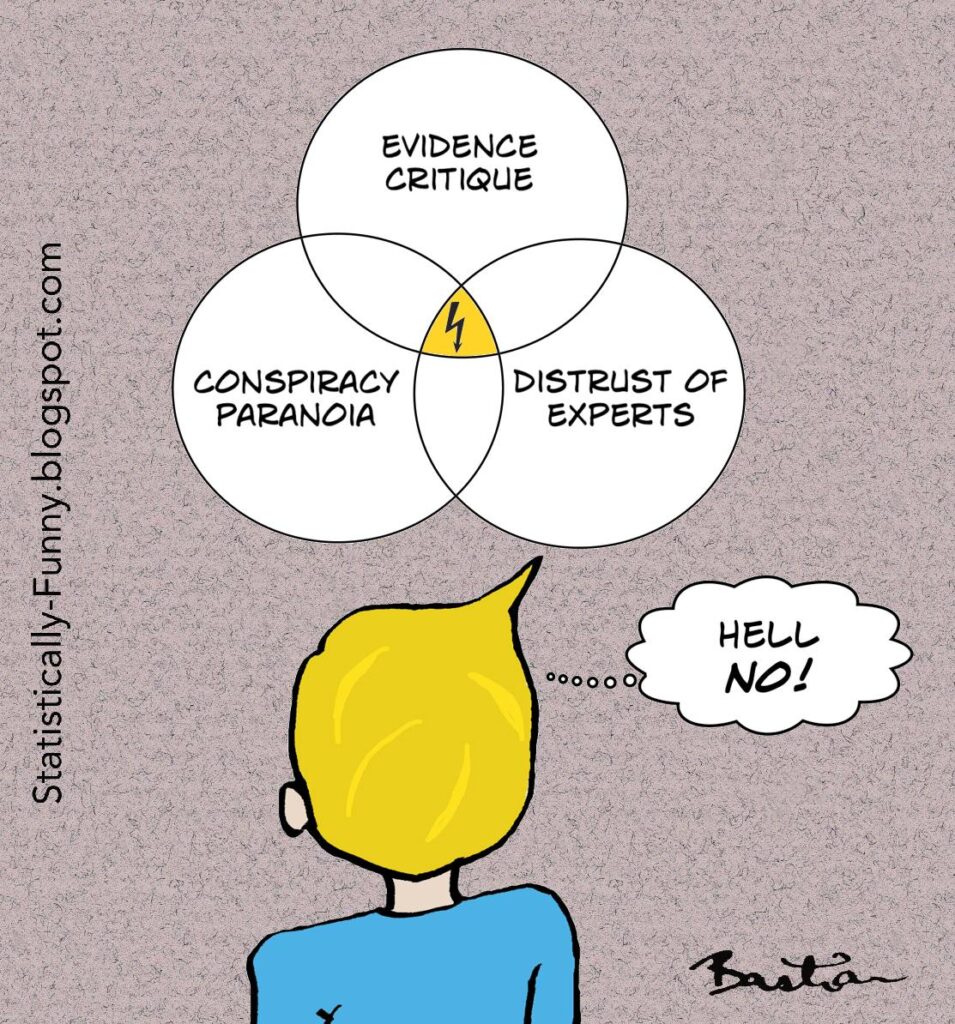

That, Gregson points out, is a pathway to another feature correlated with populism—believing in conspiracies: “If consensus scientific positions are not supported by good reasons, then the unavoidable conclusions science populists must draw is that these positions hold sway in science because of the corruption of scientists. Science populists commit themselves to engaging in conspiratorial ideation.”

Gregson is talking about influencers from physics, but the phenomena he described were instantly recognizable to me from medicine, too. So I dug into the small, but growing, base of scientific literature on science and medical populism. That quickly disabused me of my long-held conviction that evidence-based medicine (“EBM”) is antithetical to authoritarianism.

I’m no longer shocked that some prominent EBM influencers are aligned with populist communities and centers of power. Variants of populism differ somewhat—you can be a science populist but not a political one, while political populists are more likely to be science populists as well. However the overlap in some core beliefs is enough to make it unremarkable that science populists from the EBM community could, for example, join and help advance RFK Jr’s destructive enterprise, or defend it.

EBM offers tools that enable weak research and unjustified experts’ pronouncements to be challenged. However, that best case scenario is dependent not only on technical skill, but on our ability to interrogate and minimize our personal biases, egos, and interests when we critique research. Evidence critique can be weaponized, and the tools lend themselves to fostering both Dunning-Kruger effects and superiority complexes. On top of that, medicine comes with an inbuilt-Bogeyman ideally suited to conspiratorial thinking—the pharmaceutical industry and other business interests in health—and being sensitive to the risk of commercial bias is part of the EBM tool kit.

“Big Pharma” pairs well with demonizing the “academic elite,” a defining pillar for science and medical populism:

The academic elite, representing the supposed antagonist of the people, is understood as a collective of scientists, experts, academic institutions, and other actors who hold superior epistemic authority (Hartmann, 2004). Science-related populists perceive the academic elite as immoral because it allegedly promotes the production of useless and inauthentic scientific knowledge in the proverbial ivory tower (Krämer & Klingler, 2020), conspires with other elites (Harambam & Aupers, 2015), and follows elitist ideological agendas such as “multiculturalism” or “political correctness” (Ylä-Anttila, 2018).

Niels G. Mede and colleagues (2021).

For science populist influencers in medicine, conspiracy between the medical-industrial complex and the academic elite is a prominent thread in the discourse. It acts as a siren call to populists generally, along with contrarian takes on hot button issues. As populists swell an audience, soaking up the content and heaping praise on the creators, audience capture can come into play. Influencers can become “ideological entrepreneurs” who draw on “collective estrangement at times of great upheaval…while responding to innovation and profit opportunities.” (Jurg 2024) Their audience can cheer them into ever greater confidence in increasingly radical positions. The more extreme they get, the more their positions get push back from the mainstream, further fueling the cycle with claims of being “canceled” by a nefarious elite.

Here’s a definition of medical populism that draws on the tendency of populists to forge societal divisions by whipping up, or taking political advantage of, crises, threats, and moral panics:

“We define medical populism as a political style based on performances of public health crises that pit ‘the people’ against ‘the establishment.’ While some health emergencies lead to technocratic responses that soothe anxieties of a panicked public, medical populism thrives by politicising, simplifying, and spectacularising complex public health issues.”

Gideon Lasco and Nicole Curato (2019).

A year after that was published, the pandemic provided a graphic demonstration. From early in the pandemic, Guilherme Casarões and David Magalhães wrote, “medical populism addressing the coronavirus crisis has led populists to build an alt-science network that serves as a platform for doctors, lobbyists, businesspeople, and religious leaders who are—or have become—linked to far-right movements across the world….[W]e define it as a loose movement of alleged truth-seekers who publicly advance scientific claims at a crossroads between partial evidence, pseudo-science, and conspiracy theories. It comprises groups as diverse as maverick scientists, wealthy donors, flat-earthers, anti-vaxxers, and climate deniers, all united by their distrust of governments and mainstream science.”

Casarões and David Magalhães pointed to “the populist tendency to offer simple solutions to complex problems,” which Gregson also raises in his video. He says, “Like populist politicians, the science populists provide simple answers in complex subjects. They free people to believe in experts whenever they want to, and reject them whenever they feel like it. And they make audiences feel knowledgeable and empowered to trust their own intuition above experts.”

So what can we do about it? Lasco and Curato argued that “Medical populism is here to stay, and the challenge is to maximize communicative architectures that deliver the best outcomes for at-risk communities.” Scientific communities have to have plenty of room for uncertainty, and for differing interpretations of evidence and positions on policy issues. Those are critical to healthy intellectual and policy debate: How do we achieve it without enabling and empowering populist influencers?

The audience that’s considered at risk in much of this writing is the non-scientist population. But I think this can creep up on anyone. It takes self-discipline to avoid bias, especially in social and informal contexts, when we generally don’t have time to fact-check. We need to be very careful about whose influence we expose ourselves and others to, and what audiences we drift into. Movements, including science ones, pose particular risks we need to be alert to. None of us who are consuming science “content” are inherently immune from these dynamics. Perhaps the first step is to recognize the seriousness of the problem within.

From my post, Scientific Advocacy and Biases of the Ideological and Industry Kinds

You can keep up with my work at my newsletter, Living With Evidence. I’m active on Mastodon, @hildabast@mastodon.online, and on Bluesky. My Wikipedia username is also hildabast.

~~~~

The cartoons are my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny.)

Acknowledgement: I’m grateful to Katie Mack for sharing the video about science populism on Bluesky.

Disclosures: I have no income from audience contributions, including no paid subscriptions for my newsletter, no donation platform, no ad-based or click-based revenue source, and I’m not a paid expert in court proceedings etc. I maintain a list of my financial disclosures here. I have written several posts at this blog that have been critical of populist medical evidence experts as a group, some of which are included under the tag experts, and I have been taking issue with positions of some of these influencers for many years (for example, here in 2002 (page 4), here in 2018, and here in 2019). As well as having differences of opinion, I’ve been colleagues and co-authors with some in the past.