There’s a chronology of “psychology’s contributions to the belief in racial hierarchy and perpetuation of inequality for people of color in U.S.&rdquo…

How-To Guide: Help Find Missing Scientists’ Faces

Do you want to see more photos and stories of amazing women and other under-represented scientists? Sure you do! And you can help, too, even with tweets or just a few minutes every now and then. It’s the kind of thing you can do alone, and it’s ideal for doing in groups, too. It’s like genealogy, but for your profession.

It’s so important for all of us to prevent invisibility in the historical and social record of scientists who always had the odds most stacked against them. I wrote about that in my Black History Month post – and it’s full of inspiring African-American women scientists you probably never heard of, too. Check it out if you haven’t already read it.

Several people asked, “How did you find them?” This is a “how-to guide” if you’d like to join in. It’s in 3 parts, with examples and pointers:

- 5 things you can do that take less than 15 minutes;

- 7 things you can do with an hour here and there; and

- going further to pull people’s stories together.

A little or lot, occasionally or often – it all helps! It’s Women’s History Month, so it’s a good time of year to pitch in.

There’s a lot we can do on the internet, Twitter, and emailing – even reading and sharing what others produce is critical encouragement. There are things that our institutions and organizations should be doing, to reveal and preserve the historical record on women and other under-represented scientists. So let’s all do a little more!

First, some background about Wikipedia. You don’t need to get into Wikipedia editing to get involved. Publishing and pegging in other places is essential to create the sources needed to underpin Wikipedia pages.

But that last step into Wikipedia matters. It’s a massively used central global resource now. Whether it’s students, journalists, or anyone else, directly or indirectly, Wikipedia will feed into their knowledge about scientists. And it gives us all a way to contribute to the world’s accessible knowledge base.

Any contribution you can make along the pathway that feeds Wikipedia is valuable – you don’t have to do it all. The only thing that’s critical is that you leave a path to what you find. This massive crowdsourcing effort is like a relay race, where you can pass the baton to someone else – or just leave the baton conspicuously on the field so that someone else can pick it up later and run a bit further with it.

First thing to know: this is how photos and other images get to illustrate Wikipedia pages. The image has to be copyright-free, or the copyright holder has to release it. Then it needs to be added to Wikimedia Commons, the central repository for Wikipedia. The only way to have an illustration in a Wikipedia page is to pull it in from Wikimedia Commons.

5 things you can do that take less than 15 minutes

1. See a photo or illustrated story – or important news about a scientist? Fire off a tweet or email if their Wikipedia page needs a pic.

If you see a photo of a prominent woman or other scientist from an under-represented group, or one from the past, check if their Wikipedia page has a photo – and tweet, facebook, or email someone who could solve this problem if it doesn’t. The source of the photo might be labeled – or they are or have been affiliated with an academic institution or a scientific society, for example. The scientist’s alma mater or employer institution might have one, even if they’re not mentioned specifically mentioned in the story.

The story you see could be about their life, an obituary, or a major achievement – if you’ve got a few minutes, stop and check. And if they have no Wikipedia page now, still try to nail a photo for when someone gets to that.

Here’s an example where this worked for me with just one tweet. When I saw that HHMI was getting its first woman President, I checked out her Wikipedia page – no photo. So I tweeted for help to Jonathan Eisen, who roped in the HHMI Twitter account, and voilà!

Twitter can motivate an organization to make this a priority, so if you’re on Twitter, use it. Include a hashtag like #womeninSTEM or #BlackandSTEM.

People who could release a photo might not know how to use Wikimedia Commons, or might not want to do that. There are ideas below – so pass on those on, or link to this post.

2. Take a good photo and upload it to flickr or Wikimedia Commons.

If an important scientist is giving a talk at a conference, for example, and you can get a great photo close-up, that’s a public space and you can release your own photo copyright-free. All these licenses are great:

- CC-BY

- CC0

- Public domain or no copyright restrictions

- Product of US government work if you work for a US agency like NIH

Check out Wikipedia’s guide to what’s ok and what’s not, to use from flickr.

3. Ask the scientist themselves, or a family member, to release a photo.

Unlike writing about yourself on Wikipedia, there is no conflict of interest in uploading a photo.

That’s how I got a photo of Judith Lumley into Wikipedia: I asked her son, Thomas Lumley, who I met on Twitter, to upload one.

3. Add a link to the source for a photo – or add an eligible photo – to Wikipedia.

If you don’t know how to really edit Wikipedia, I’ll follow this with some starter tips. But whether you or you don’t, adding a link to a photo you’ve found to leave a trail for someone else to follow is quick and easy.

The best way to do this is to add it to the page itself. If a reader is interested in the person, seeing them can be inspiring. I’ve started doing quite a bit. Harvard for example, has a really inspiring of Mary Logan Reddick in their collection. She got her PhD there at Radcliffe College, she’s probably the first African-American to win a Ford fellowship to go abroad to work on her science. So I added this section showing how to find that photo.

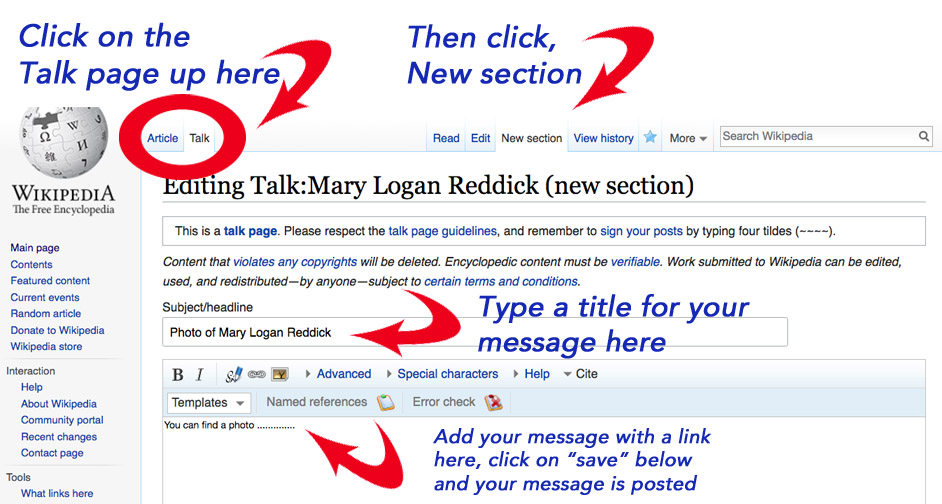

Even quicker, is leaving a message on the talk page. You can do this anonymously, without signing into an account. Here’s how I could have done that – click on the image to see a bigger version:

If you would like to take the plunge with editing Wikipedia, find someone you know who does it, and get them to show you. Or keep an eye out for a Wikipedia edit-a-thon in your neck of the woods – it’s a great way to learn and get the bug. Or try the Wikipedia Adventure – and there’s the Teahouse for support, too.

There is also a Wikiproject on Women in Science – more about Emily Temple-Wood and the start of the project here in Buzzfeed.

4. Add your social media support to people trying to find missing scientists’ faces.

Encouragement, thanks, and praise matter! It’s not just that encouragement can spur the result you’re after. It can also draw the attention of someone else who might follow suit and start making women scientists and those from other under-represented groups more visible.

And it’s important for us, too. Stop and pay attention, click on stories about diversity in science. We have to counteract the impact the overwhelming white-maleness of science’s image is having on our psyches.

5. Suggest an organization you are involved with document honors and biographically important contributions online.

I bet you are involved in, are connected to, or see an organization that has key information that should be online, so that people searching the internet to write their stories can find it. If you notice that, fire off a tweet or email, or make a suggestion on their Facebook page.

You would think everything’s online these days, but it’s not. People give out awards, but don’t have the full history of honorees online. You can’t see who the first woman or person of color President an organization had because office-bearers aren’t all online. Women’s achievements in professional roles aren’t seen, because the organization doesn’t put that history online.

Here’s an example where I did that, when I was looking for a past-President of Graduate Women in Science – click on the thread and you will see that they’re now on it (or at least might be):

7 things you can do with an hour here or there

1. Find a photo!

This can be a harder slog than it sounds – which is all the more reason to follow up on one you notice in a story or on social media when you’ve never seen it before. Seeing a photo used in different contexts could give you more information about it – such as when and where it was taken, and who holds any copyright. (More about crossing that bridge soon.)

Some starting places:

- Google Images (where the limits on licenses seem to be based only on flickr and Wikimedia Commons)

- Articles or blog posts about the person will usually show up in the Google Images search, but also check out obituaries and bios in the scientific literature

- Institutions where the scientist studied or worked

- flickr, where using the limits on licenses works well

- Wikimedia Commons, because they can be hard to find, or one can be added after a person made a page for the scientist

- Google Images (where the limits on licenses seem to be based only on flickr and Wikimedia Commons)

- If your institution has a subscription to LexisNexis, you can search old newspapers there – and there’s also newspapers.com

Here are 9 women who could be pursued with the institutions they have been associated with (I couldn’t find copyright-free ones on the Internet). If you work on one, please leave notes in the comments here, tweet me directly (or email me at my Twitter handle @ gmail) so I can update this list:

- Gloria Hollister Anable (1900-1988), “explorer, scientist, conservationist”, Connecticut College, Columbia University, New York Zoologist Society (now Wildlife Conservation Society)

- Matilene Spencer Berryman (1920-2003), oceanographer and attorney, American University, University of Rhode Island, US Naval Oceanographic Office, University of the District of Columbia (photos at Howard University)

- Inés Cifuentes (1954-2014), seismologist, US Geological Survey and Carnegie Academy for Science Education

- Aprille Ericsson (b 1963), aerospace engineer, MIT, NASA (beautiful photo with autobiography on defunct NASA page – photo may be a US government work, an example of a more recent one at a NASA event) – [update] Dalmeet Singh Chawla reported on the project in Nature, and included a recent photo with the right license: found it in Twitter and added (12 March).

- Etta Zuber Falconer (1933-2002), one of the first African-American women to get a PhD in mathematics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Fisk University, Emory University, Spelman College, Norfolk State University (examples of photos of her)

- Betty Harris (b 1940), chemistry of explosives, Southern University, University of Atlanta, University of New Mexico, Los Alamos National Laboratory (photo at the National Academies of Science)

- Ruby Puryear Hearn (b 1940), biophysicist, Skidmore College, Yale University

- Jennie Patrick (b 1949), chemical engineer, Tuskegee University, MIT

- Mary Logan Reddick (1914-1966), neuroembryologist, Radcliffe College (Harvard), Ford science fellowship, Cambridge University, Morehouse College, University of Atlanta

2. See what your institution does for remembrances like Women’s History Month, Black History Month, and Hispanic Heritage Month

There could be a goldmine of resources that aren’t necessarily obvious on the website, especially when websites have been re-designed from time to time. There could real finds in here, of photos and bios to pin onto Wikipedia pages.

What’s more, they might be looking for suggestions for people to cover in future. If you’ve formed a group at your institution, they might be interested in covering what you’re doing.

3. Walk someone through to getting a photo released online

There are several ways that you can get a photo made more accessible, if someone can’t or prefers not to try to use Wikimedia Commons directly:

- Getting it digitized and online if it wasn’t online already – an institution will have rules and procedures for this

- Uploaded into flickr with the copyright released (see point 2 in the first part of this post) – from there with that status, someone else can upload it in Wikimedia Commons

- Have the organization note a suitable public domain license on their own website, where they use the picture

Here’s an example of that third path – it’s probably the easiest thing to do for most organizations to do, once they have established they can release the photo. The Director of the Duck Research Laboratory at Cornell University, Gavin Hitchener, was able to get “public domain image” added to the photo with Jessie Price:

Wikipedia has guidance on copyright rules: here’s a starting point. Up in the second point in the previous section of this post, I listed the main types you’re looking for. If the photo was definitely taken in the US before 1923, for example, then copyright has expired. After that, it gets complicated.

If someone is willing to give release copyright, but using flickr or Wikimedia is too big a hurdle, you can upload to Wikimedia Commons, and they can send an email releasing copyright. An “OTRS” option for that comes up when you upload – but here are details for that email.

Even a photo on a website or flickr with limitations to it, such as only being released for non-commercial use, is better than no photo on the internet at all. Don’t be disheartened: if you lose one, try again. It’s a great feeling when you liberate one!

4. Find bios, obituaries, or their publications in your science’s literature for a woman or other scientist from an under-represented group

I’ve focused a lot on photos, but that’s not the only thing matters. There are lots of flimsy bios out there, ones with mistakes in, and ones that have a lot of info about a person’s life – but almost nothing about their scientific work.

If you’re a scientist, you’ve got access to literature that the non-scientist journalist or Wikipedian might not. A quick literature search could turn up an article or more that you can attach to the Wikipedia page for someone else to incorporate more fully later (or to come back to yourself).

And if an important woman or other scientist from an under-represented group dies, and you are at all in a position to step up to write an obituary, at a journal, newspaper, or anywhere else, do it. Obituaries are critical to the record of a notable person. Consider the implications of this: in the New York Times, a whopping 75% of the obituaries are of men.

5. Find important achievements by under-represented and women scientists in your field and see if they are credited in Wikipedia

Eva Klein has had an extraordinary life – and a life of extraordinary achievement. I came across her when I felt like doing a Wikipedia page one weekend, and thought I’d look through a timeline of milestones in immunology, and see if that turned up any woman needing a Wikipedia page. That’s how I found that Klein is responsible for the line of work that discovered natural killer cells – and she christened them that. (Pictures and more information about Klein would be wonderful – she’s at the Karolinska.)

Starting a Wikipedia page for the first time is complex. So I wouldn’t recommend jumping into that without help from an experienced Wikipedian. But sometimes, scientists’ major achievements aren’t noted on their Wikipedia page, and that’s easier. I wrote about an example of that in my previous post, Alexa Canady.

Even more commonly, the woman or under-represented scientist isn’t mentioned in the history of the scientific development. That was the case with the amazing Judith Vaitukaitis and the home pregnancy test: I added a section on her contribution to the pregnancy test page. This is the easy way to flag that a scientist may deserve a page of their own.

If you type in a sentence about the scientist’s contribution, you use the hyperlink symbol on their full name: when it tells you, “Page does not exist”, you hit “insert link” anyway. And that turns it into one of those red links you’ll see a lot of on Wikipedia. That is basically a request for a page for that person. That leaves a marker someone else can pick up on. And when the page is created, it will automatically be linked.

6. Start a group in real life or social media to band together to discover the missing scientists’ faces at your institution or in your field

‘Nuff said!

7. Take a photo of a monument or plaque that honors a scientist and upload that

You could be out and about and notice a street is named after a scientist from an under-represented group. Or there’s a plaque to honor a place they lived and worked. Or there’s a sculpture. For example, if you’re in Denver, if you’re in the area, you could visit the sculpture of Justina Ford that’s across the street from the American Black West Museum, and take a photo of that.

Pulling people’s stories together

Writing about a person can be an enormous undertaking – but outlining the basics about someone doesn’t have to be, especially if you have multiple sources to draw on. And you can publish a story about a little-known or prominent scientist in a professional journal – you don’t have to be a historian.

Publish a story or obituary in a journal, newspaper, or blog post that will be preserved

I’ve talked a lot about Wikipedia, because it’s so central. But Wikipedia is the end of the line, really. You can only have a (proper) Wikipedia page if there are sources to draw on. Sometimes, that’s what has to happen.

I’m at that stage now with Jane Hinton. As I wrote in my last post, I started a Wikipedia page about her. And there was a lot of interest in her:

But now I have gathered a lot more about her from primary sources. So it’s time to write an article, and return to Wikipedia to expand later.

Have a look at the articles in the specialized journals for your area of science to see if they include articles about individual scientists, or articles about a group of influential scientists. They might include obituaries too. You can pull together an article alone, or a group could get together and write an article about leading or pioneering women or other diverse scientists in the field.

Your institution (or the institution “your” scientist was/is affiliated with) may be interested in a blog post/website article. Other blogs will be too – but make sure it’s one that is being preserved by the Internet archive.

Some places to get you started if you’re looking for a woman and/or scientist from another under-represented group to write about:

- Search Google Books – for quite a lot of anthologies of scientists, you’ll be able to browse the list of chapters, and search for a bio: if it’s only short, the whole thing may be visible.

- Posts for one of the “months” at an institution or science society.

- Ebony magazine often interviews African-American scientists – and their back catalog is all online (see for example this search for the word scientist).

- SACNAS is a project that’s “Advancing Chicanos/Hispanics & Native Americans in Science”. They have a biography project, with bios organized by scientists’ last name, their field/discipline, and with women in a separate list.

(Add more suggestions in the comments.)

Get to know how the library at a science institution works – especially if you work at one

That’s from an interview with someone I was doing some research on at the Wellcome Trust library in London. That’s science, isn’t it? But it’s also what it can be like to get into the historical holdings at a library.

Here’s a photo I took on Friday at the National Library of Medicine at the NIH (with thanks for the permission to do so):

This book about Justina Ford contains extraordinarily rich information. Ford was born only 6 years after the end of slavery, and there’s information about her family’s life under slavery that’s crucial to a picture of the times and its legacy. It also showed there are several errors in her Wikipedia page – an important reason for real effort to go into these stories. Sometimes, as here too, even errors in people’s names take on a life of their own. (I haven’t updated her page yet, but I will.)

This picture is also here to show what it’s like to research in historical collections. The rules are different, from library to library. Sometimes you can’t take photos – other times, you can just record everything on your phone and be in and out quickly. In some, they have cameras you can use, with a fee per page you copy. Only lead pencils and notepaper might be allowed in other libraries. But either way, do your homework ahead – not just about security, but to have found the boxes or books and photos the library is holding that you want to see, so you can make an appointment to see them.

Sometimes, you won’t even need to go: they will scan and email you what you’re looking for. Libraries with the history of science and institutions are great to visit though.

Libraries are wonderful places. The pieces that tell the stories of people’s lives are kept safe, and the scientists are in wonderful company.

But let’s not leave them only in there.

~~~~

“Plot twist”: Jesse Jarue Mark (b 1906, date of death unknown), used to be on the list of women here. She is widely credited with being the first African-American woman to gain a PhD in botany, Iowa State College. Bryan Clark took up the challenge of getting her image – and found that JJ Mark was a man. A mis-spelling, “Jessie”, seems to be responsible for the inaccurate historical record her. JJ Mark is still a very early recipient of a PhD in botany among African-Americans: if anyone can find a picture, that would be great! (ISU has one, but it’s copyrighted.)

Cartoon at the top of the post, and the photos of and in libraries and institutions are my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More of my cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

The montage is my own work, made of photos I added to Wikimedia Commons, mostly in Black or Women’s History Months (CC-BY 4.0).

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.