This is my fifth annual research roundup about journal peer review. And we’re only averaging about one randomized trial a year. This…

Bad and Good(-ish) News on the Abstract Spin Cycle

Abstracts are central to the science communication process. The words in them can lead searchers to find a paper. Because they’re the most read part, their messages can be the only take-aways. And they can determine whether or not someone goes on to read more of the work. If they’re free to read and the rest of the paper is behind a paywall, it won’t even be possible for everyone to go further.

All of which makes spin in abstracts a menace, whether it’s misleading cherry-picked content – like including the only “significant” result – or garden-variety hype. When I last wrote a post on the evidence about abstracts, Isabelle Boutron and colleagues had reported on a trial randomizing cancer clinicians to evaluate abstracts of clinical trials with and without spin. The participants were all themselves corresponding authors of clinical trials, so not your average clinicians. They were more likely to say a treatment was beneficial if they’d read an abstract with spin – but also more likely to want to see the full paper.

Earlier this year, Heppy Khanpara and a colleague published a report on a similar trial. In their much smaller trial, practising physiotherapists in India were randomized to an abstract of a clinical trial: again, it was either with its original spin intact, or with the spin stripped out. And again, the spin had an impact on views of the treatment.

The Boutron trial has guidelines for how to remove spin from an abstract for a clinical trial, and many of the steps would be useful for other kinds of abstracts, too. One important step, though, isn’t explained, which doesn’t help much: “Delete linguistic spin”. They did that in 6 of the 30 abstracts they used in their trial. But if you wrote the spin, how likely are you to detect it?

In a paper the following year, Boutron and colleagues explained what they meant by linguistic spin: “rhetorical manipulations to convince the readers of the beneficial effect of the treatment such as ‘excellent’ results, ‘encouraging’ outcomes, ‘a trend toward significance’.” Other examples they gave: “high potential” and “considerably helps.” I wrote a quick checklist for writing abstracts, including: “words like ‘promising’ and ‘novel’ are danger signs. You want neutrality and objectivity: adjectives and adverbs – any superlatives – are risky.”

Two large-scale studies related to linguistic spin were published in the last few weeks that help flesh this concept out. They make it clear, though, that we don’t all agree on what words are inherently over-positive.

The first came from Ju Wen and a colleague, on adjectives and adverbs in journal articles. Their primary concern in that paper is readability, and cluttering scientific writing. They had published another similar study a couple of years ago, where the focus was on promotional language, aka hype, in abstracts and full papers (with Xiaoke Cao, 2020). Both papers concluded there’s been a large increase in promotional words in the last couple of decades. The 2020 paper looking at abstracts and full texts separately found the problem was far greater in the abstracts.

The second recent paper comes from Neil Millar and colleagues, and it looks at hype in the abstracts of successful grant applications to the NIH from 1985 to 2020. They also concluded that levels of hype have increased. (Millar also had an earlier relevant paper, on hype in randomized trials.)

What’s different, though, is what these groups consider to be hype. The first group applies the same method as Christiaan Vinkers and co, from a study published in 2015. Vinkers concluded that the use of positive words in abstracts in PubMed rose from 2% in 1974-1980 to 18% in 2014. In comparison, negative words went from 1% to 3%, and there was no increase in neutral or random words – or the use of positive words in books. These are their hype words:

Amazing, assuring, astonishing, bright, creative, encouraging, enormous, excellent, favourable, groundbreaking, hopeful, innovative, inspiring, inventive, novel, phenomenal, prominent, promising, reassuring, remarkable, robust, spectacular, supportive, unique, unprecedented.

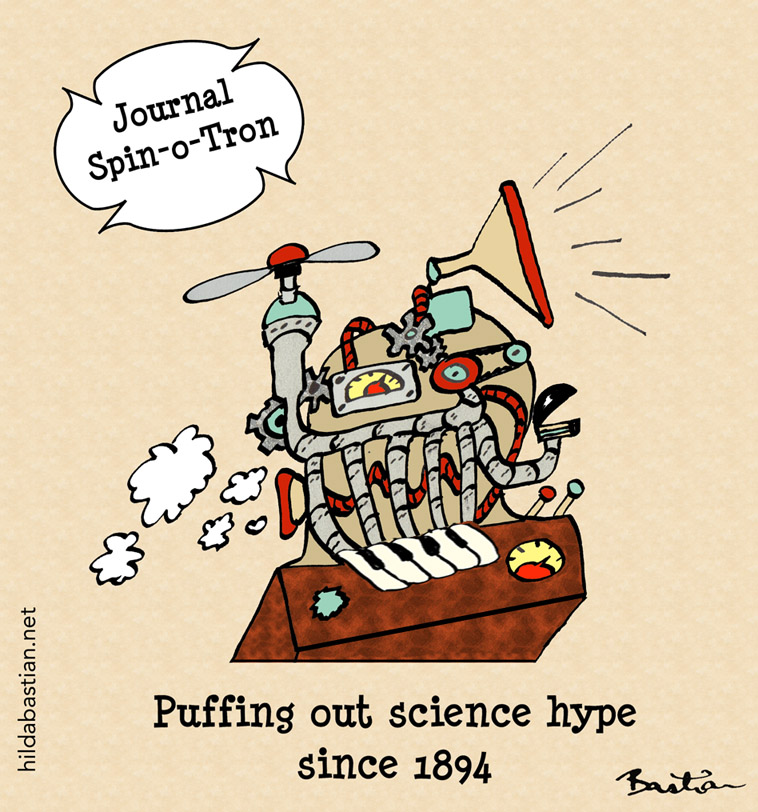

I personally agree with almost all of those, but would really want to know how much weight the individual words carry. For example, bright, favourable, prominent, remarkable, robust, and supportive all have decidedly non-hype uses – like supportive care. To do at least a little check on whether hype was increasing rather than results being inflated with non-hype, I picked out one of my pet hates to use as a sentinel test word – the target of that cartoon of mine earlier. I ran promising in PubMed, and for what it’s worth, that one word has been on the rise, though it’s rare:

The second group of authors designated 139 hype adjectives. They’re listed here, along with individual frequency of their use. I think a lot of them would be controversial. For example, they include diverse, interdisciplinary, reproducible, and systematic. Some seem to me to be more reflective of language trends: are words like seamless (up 6,600%) and scalable (up 13,029%) hype, or essentially meaningless buzzwords du jour?

In the end, I think these studies do suggest hype is escalating. And warning that adjectives and adverbs are dangerous territory for scientific reports is still solid advice. But I don’t think we’re anywhere close to a good style guide here. It might help if we could get wider agreement on what words should be strictly verboten in journals. Although saying “might help” is full wishful thinking at this point, when spin researchers are still calling out trending to significance.

So what’s the good(-ish) news I found when I was catching up on research on abstracts? I found a couple of things worth pointing out.

A pair of systematic reviews in the last few years concluded that journals adopting reporting guidelines for abstracts seems to chip away at this problem, though not much (2018 and 2021). It’s not enough improvement to push abstracts from poor to good quality – they’re just less poor. But at least it suggests the situation isn’t hopeless. (Disclosure: I’m co-author of one of those reporting guidelines.)

The other point is a concept Millar and co discuss. It’s not new, but the jargon was new to me. It’s called “semantic bleaching”. That’s when words are “used with more exaggerated meanings (ie, hyperbole), until its overuse ‘bleaches’ out the stronger meaning of the word.” Thus, today’s hype might just fail to do any harm eventually. That’s not much consolation though, when it seems so easy to generate new ways to exaggerate with language. We need a journal and science culture that scrupulously rejects the urge to hype, and strips it out like we’re all well-trained spin researchers.

~~~

More Absolutely Maybe posts on abstracts.

Disclosures: I am a co-author of the PRISMA reporting guidelines for abstracts of systematic reviews. I have unfortunately contributed to the huge pile of conference abstracts that have never been published, including co-authoring 2 assessing the quality of abstracts (1998a and 1998b).

The cartoons are my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny.)

Data notes for “promising” graph

I searched PubMed from 1975 to 2021, because abstracts were not generally included in PubMed records before 1975. The data for the chart are here. I searched for the word promising in the title or abstract, and for the number of PubMed records with abstracts: