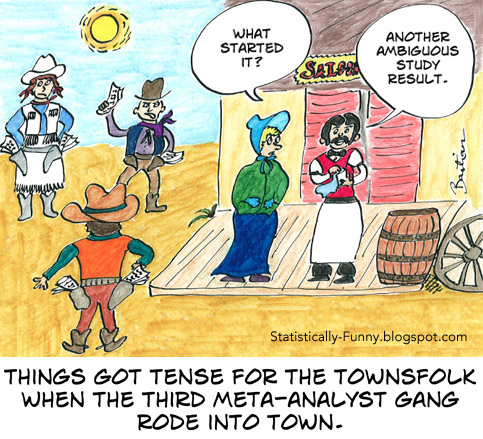

Network meta-analysis (NMA) is an extension of meta-analysis, combining trial evidence for more than 2 treatments or other interventions. This type of…

Is Critical Appraisal Training for Clinicians Doomed? (Sicily Conference Part 2)

The first shot against critical appraisal training for clinicians came quickly – in the opening lecture, in fact. And it seemed to me, every time there was any presentation related to teaching, question time would include someone lobbing another grenade at the concept. In fact, I’d say it was one of the main recurring themes at this year’s Sicily conference for evidence-based healthcare teachers and developers. (I discussed the main ones in the first part of this series.)

Could critical appraisal training be on its way to becoming a relic of history – and should it be? Right from the start, the argument raised several questions for me – and at times, the way it was framed made me super uneasy.

That opening lecture was by Gordon Guyatt – the GRADE pioneer, who also coined the phrase “evidence-based medicine” back in the early 1990s. It was just a small part of his talk, but he cited this essay he co-wrote with Kari Tikkinen that digs into it. He argued that teaching all clinicians how to essentially do a risk of bias assessment for a primary study (like a clinical trial) doesn’t work, because it’s not enough to achieve proficiency, and they don’t use it enough later on to affect their practice – or to solidify and extend the skills.

Meanwhile, Guyatt said, citing an international survey he, Tikkinen and others co-authored in 2016, even clinicians with some exposure to relevant education don’t understand outcome statistics from meta-analyses that are critical to well-informed evidence-based practice. Critical appraisal should be left to the experts, went the argument, and clinicians should be taught the skills they need to appreciate evidence basics and how to interpret and use evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and summaries of systematic reviews.

The leaving it to the experts part is what made me so uneasy, and I’ll come back to that. But questions and concerns bubbled up for me about the basic argument for a different focus in evidence training, too, and more popped up every time anyone else mentioned it. For starters, I wanted to know how the evidence from randomized trials of critical appraisal versus alternatives was shaping up: Is there strong evidence of absence of important effects of critical appraisal training – or that an alternative approach works much better?

What’s more, clinicians don’t score well on understanding statistics that have already been taught in courses alongside critical appraisal of primary studies for years: Why were people confident that all that was needed was a shift in focus of the curriculum to solve the problem? And where would this strategy leave clinicians when there’s no recent reliable clinical practice guideline or systematic review that can help for a patient’s situation? Or, as so often happens, various evidence-based sources and experts disagree on what’s best? Those areas of disagreement tend to be where studies are riddled with ambiguous and conflicting results. Often, there are discordant reviews because people are responding to systematic reviews they disagree with by doing their own.

While I agree clinicians need to be able to use reliable meta-level evidence, we also need as many clinicians as possible to be equipped to be critical when a primary study sweeps the media, and weigh up the strength of the arguments that follow – or a pharmaceutical rep shows up in their orbit, clutching reprints of a trial they claim should change practice. Further, we need a large pool of clinicians to populate those clinical practice guideline panels, able to be critical all along the way.

I wondered, too, what outcomes people had been hoping for, and measuring success or failure by. Later, I read this in the Tikkinen and Guyatt essay, “the notion that most clinicians emerging from professional training will regularly evaluate the risk of bias in methods and results of primary studies is deluded.” Is that how high they set the bar? If so, no wonder they were disappointed!

I still remember my first critical appraisal training vividly. I was a consumer advocate at the time, and really thirsty for it. It would have been the mid-to-late 1980s. Between then and about a decade ago, I guess I had a few dozen experiences of participating in, designing, or teaching in training courses that fit the category – generally for patient and consumer advocates or journalists. (I’ve detailed that under this post’s disclosures of interest.)

As far as I can see, my first encounter must have been in the first decade of this teaching trend. By 1980, results of trials of critical appraisal training were appearing. When I got home from the Sicily conference, I checked for evidence. A fairly recent systematic review made it easy. It’s a systematic review of the systematic reviews on teaching evidence-based healthcare practice, with 22 reviews of 141 primary studies of various types. From the subset of studies that compared critical appraisal methods to something else, the authors concluded:

Teaching critical appraisal as compared to no teaching (or pre-test) was associated with consistently reported increased knowledge across all studied populations, [28, 33, 39, 41, 44] improved skills in undergraduates [33]. Such interventions were associated with less consistently reported improved skills [28, 33, 36] and behaviour [33, 36, 41] in postgraduates, change in behaviour in undergraduates [33] as well as less consistently reported improved attitudes and inconsistent results regarding skills and behaviours in mixed populations [39, 44]. Only one study reported certainty of evidence as low for knowledge and very low for critical appraisal skills [28]*….

For health professionals, multifaceted interventions with hands-on activities on the development of PICO question and searching, as well as discussions and critical appraisal improved knowledge, behaviour and attitudes, or skills, respectively.

Bala et al (2021)

* [28] is a systematic review from 2011.

A severe limitation to this evidence is its focus on assessing short-term outcomes. There isn’t a strong basis for showing any particular type of education results in longterm improvements in clinical practice and health outcomes.

Still, this definitely doesn’t add up to a strong case for scrapping critical appraisal training. And so far, I don’t think there’s a strong case for a specific substitution of that part of a curriculum. I’ll follow this argument with interest in the future – but for now, I’m not adding my voice to the call for consigning critical appraisal training to the dustbin.

A major driver of the movement for evidence-based healthcare was to overturn a culture we often described as “eminence-based”. That wasn’t just about ensuring that there was a strong evidence base to draw on, instead of only the opinions of clinical experts and whatever studies they wanted to brandish. It was also about trying to enable everyone to be more critical of what experts handed down from on high. Now, a few decades later, the language people are using suggests a disturbing number of us may be slipping into comfort with ourselves in that old-school role, just armed with our takes on evidence.

I’m not starry-eyed about the ability to equip people with critical appraisal skills. I often discuss the limits of teaching critical thinking skills generally, and I’ll link to my most recent post on that below. I don’t believe there’s no way that “traditional” critical appraisal sessions could be improved upon. I hope people keeping finding and demonstrating ever better ways to enhance evidence consumer skills, and how to spread them far and wide. I’d just like it to come with a more socially transformative agenda, and without a side order of “trust me, I’m a meta-analyst.”

My recent Absolutely Maybe post related to the limits of teaching critical thinking: Philosophy, Scientific Literacy…and Flattery.

~~~~

Disclosures: I was invited to give one of the keynote presentations at this conference, with travel support from the organizing group (the non-profit GIMBE Foundation). The categories of sponsors accepted for the conference are listed here, and do not include manufacturers of drugs etc. In terms of the evidence “tribes” with a strong presence at this conference, I have a long relationship with Cochrane and the BMJ, and I was a member of the GRADE Working Group for a time long ago.

My first experience of critical appraisal training was a short stand-alone workshop by the amazing Judith Lumley – a fabulous epidemiologist I wrote about here. Realizing that the skills you need weren’t out of my reach was exciting. Then in 1990, I grabbed at the chance to attend a critical appraisal course run by Iain Chalmers. This was a few years before he started The Cochrane Collaboration, and it was the first time I’d met him. Running his course outside the UK was a first for him, too, as was having a consumer advocate sign up.

I was so keen, that eventually I developed critical appraisal training for patient and consumer advocates, running them in several countries, including in Africa and a memorable version in central and northern Australia for indigenous community health workers. That was many, many years ago – though I did participate in, and then was part of the faculty for, a couple of the NIH-sponsored several-days critical appraisal bootcamp for journalists in the US run by the powerhouse combo of Lisa Schwartz, Steve Woloshin, and Barry Kramer. (That wonderful program returned in 2023, now under the banner of the Foundation established to honor Schwartz’ legacy.)

The photo of ancient amphitheater at Taormina, Sicily in October 2023 is my own (CC-BY-SA 4.0).