I hadn’t been aware of the term science populism until a video about it did the rounds recently. It was a light-bulb…

Systematic Evidence and the Covid-19 Stress Test: Pass Or Fail?

You would think a time when we needed to be able to “follow the science” would have been systematic evidence’s shining hour. Yet we’ve seen questions asked like “Will Covid-19 be evidence-based medicine’s nemesis?” and is it “the new nihilism?” Some are arguing the approach needs re-defining. From the pre-existing systematic review base that often guided early decisions about travel restrictions, masks, and school closure, to systematic and living systematic reviews on the run – what’s gone wrong? What’s gone right? And what now?

This is the subject I tackled in a talk for the online “conference”, Virtually Cochrane 2021 on April 22. I’ll re-cap points I made here, plus address some of the questions that came up afterwards. (For those with access to the presentation, links for the slides are below this post.)

Systematic evidence was like a chain that turned out to have both strong and weak links. And I think it’s helpful to think of what went under the pandemic stress test in 3 parts – systematic evidence, the skills and methods used to deal with evidence systematically, and high-profile proponents of systematic evidence.

They are linked, so that weaknesses in each can weaken the whole. Much of the disillusion that we saw, I think, was because people were so disappointed in some of the highest-profile proponents of “evidence-based medicine” during the pandemic. But these 3 elements are separate, too, so let’s go through them one by one, looking at some cases to draw out the issues – starting with systematic reviews, and the critical perspective of before, during, and after the pandemic. That’s truly a continuing cycle, because each time’s “after” is the “before” we leave for the next time.

Case 1: Convalescent plasma

Before: When the pandemic hit, a systematic review from 2015 on convalescent plasma for respiratory infections was seized on to advance the idea of using this for Covid-19. The search for evidence was in 2013, with no randomized trials found, and the authors came to this conclusion: it “may have a clinically relevant impact”. In August 2020, this became one of the pillars of evidence the US FDA used to support an emergency use authorization for the treatment. The search for this historical side of the evidence wasn’t updated.

When the pandemic started, though, a more up-to-date systematic review was undertaken. Published in July 2020, it too was for severe respiratory infections, but with a search in March 2020. And it found 4 randomized trials – 2 were done by the NIH, so they were by no means obscure – plus non-randomized evidence from SARS and ebola epidemics that hadn’t been included in the old review. Conclusion? “No convincing evidence” of benefit, and the possibility that it “has minimal or no impact”.

During: There was an excellent Cochrane living review of convalescent plasma specifically for Covid-19, with versions in May, July, and October. Conclusion? “Uncertain whether…beneficial”.

Then in January 2021, an “Incredible Hulk” arrived – that’s what I call a trial so big, it smashes all the other evidence. For Covid-19, that’s the UK’s astounding RECOVERY trial of course.

In January, they stopped the convalescent plasma arm of the trial because of the treatment’s lack of benefit. (The publication of those results is out now, after an earlier preprint.) When a giant result like that lands – this was over 11,000 people – it’s just going to totally dominate the evidence.

And, indeed, when a systematic review of convalescent plasma for Covid-19 was published in February, that’s just what the RECOVERY trial did. There were 9 inconclusive randomized trials and the thumping big answer from RECOVERY. The systematic review’s conclusion was no evidence for “decrease in all-cause mortality or…any benefit for other clinical outcomes”.

You would think that was it, then, right? But the advocates of the treatment that had propelled it to such massive use in the pandemic weren’t daunted. Far from out. In April they were on the offensive about the fall of the treatment, asking, “Did Convalescent Plasma Hesitancy cost lives?” And answering that they believed it had.

Meanwhile, when I searched the Epistemonikos database in April, I found around 60 recent systematic reviews of convalescent plasma specifically – that’s right, 60! And that Cochrane “living” systematic review, of course, became instantly dramatically out-of-sync with the evidence in January when the RECOVERY trial landed. When there was no update, it ceased to be among the land of the “living”.

That saga features 3 of the recurring themes of the pandemic and systematic evidence to me: the cacophony of competing systematic reviews, non-financial conflicts of interest in weighing up evidence, and the impact of Incredible Hulk studies in emergencies and systematic reviews.

This discussion about the Incredible Hulk and systematic reviewing prompted some questions from Karla Soares-Weiser that I needed time to think about: How fast is fast enough during a global health crisis, and what could/should the role and response of systematic reviews be for platform trials like RECOVERY?

How fast is fast enough? It depends on the harm of not responding, I think. If a trial unquestionably flips the knowledge base in a critical way, I think that should at least be noted on a review very quickly – and if a review is getting a lot of attention, “very quickly” to me means within days. With a trial of that magnitude in a health crisis, systematic reviewers should know about it, and have had plenty of time to develop a plan for what to do when its results land.

Let’s consider the timeline for the release of results mentioned above for this example:

- January 15: RECOVERY trial press release.

- February 26: Systematic review with meta-analysis incorporating the press release data published in JAMA.

- March 10: RECOVERY group’s preprint of detailed results went live, including a meta-analysis incorporating the new trial’s results with those from previous trials.

- May 14: The RECOVERY trial results, with meta-analysis, published in The Lancet.

There are several ideals in there, including a trial ending with an updated analysis of all trial results. That’s unusual – even the RECOVERY trial didn’t do that for its later publication on hydroxychloroquine, where it wasn’t the first trial either. (Note: when a Cochrane review was published on hydroxychloroquine for Covid-19 in February, it included the preprint data from RECOVERY.)

There are several possible relationships here, between systematic reviewers and those running trials like this: in informing the trial at the start, in supporting the fastest possible meta-analysis – perhaps even parallel with preparing the trial results for release – and then ensuring other systematic reviews respond well and nimbly afterwards. It suggests plenty of scope for planning, and for coordination of resources.

I think the convalescent plasma example shows that it could be feasible to incorporate results of an “Incredible Hulk” in an existing systematic review within weeks, not months. If there are other smaller trials that aren’t going to make a major difference, I wouldn’t be bothered by them being left out in the interim, as long as the Hulk was in. The next example shows the problems that arise when you don’t scramble to adapt to the Hulk’s smash.

Case 2: Hydroxychloroquine

This example starts when the RECOVERY trial smashed this question – that was in the first week of June 2020. In the last week of July, BMJ published a living systematic review and network meta-analysis of drug treatments for Covid-19. A network meta-analysis is a complex process of direct and indirect comparisons to compare treatments with each other, even if they haven’t been in head-to-head trials against each other.

Even though the RECOVERY trial had come out, they went ahead and published without it. And this is how their summarized overview of results on hydroxychloroquine came out – zero in on the green square the green arrow is pointing to:

Despite the fact that they knew the evidence showed hydroxychloroquine doesn’t really work, their system gave the drug a green light for being the most beneficial treatment for a particular outcome. And it was an outcome that other trials just didn’t measure, so it was a real outlier – and this anomaly made for a very misleading piece of communication. (I wrote a rapid response at the time, which led to them making some changes to this.) Of course, proponents of hydroxychloroquine were pretty quickly waving this outdated-as-soon-as-it-was-published review as support for the treatment.

The messages from this story? Pre-specifying your rules and sticking to them are hallmarks of systematic reviews of evidence – but doing it can also lead to harmful messages. And critically, I don’t think there is adequate evidence about the effects of the data visualizations and summary elements of systematic reviews – including the summary of findings table and plain language summaries of Cochrane reviews. Since these could be among the most widely read parts of reviews, the knowledge base for them should be commensurate to their importance.

This one prompted another question I needed to think about. It was from Sally Crowe, who wanted to know if I could prioritize research into the ways summaries of reviews are presented, what would I fund and why? I’ll be digging into this question for the plain language summaries sometime soon. So I’m going to sidestep it a bit now.

But there’s one thing I’m sure about. A pre-requisite would be that studies avoided the biases that have limited the reliability of this area of research so far. A starting point is to have the work done by people from outside the systematic review provider community. And it’s critical that these communication interventions be evaluated with people who are more representative of the vast bulk of users, not convenience samples drawn from people attending Cochrane workshops or from insiders’ networks.

Case 3: Face masks

Before: In April 2020, I found 7 systematic reviews of masks of the evidence before Covid-19. I wrote about them here at this blog. And here’s what I concluded about them:

- A review would be misleading if it didn’t analyze use by infected people;

- If it was restricted to randomized trials only, it would miss critical pandemic-specific evidence (from SARS in particular); and

- Reviews really needed to grapple with indirect (mechanistic) evidence to give a reasonable picture.

One of those reviews was a Cochrane review, with versions in 2007, 2010, 2011, and then 2020, during the pandemic. Here are the later versions’ conclusions on masks for the general community:

- 2010: “simple mask wearing was highly effective”

- 2011: “transmission barriers effective…[Masks] were the most consistent and comprehensive supportive measures”

- 2020: “There is uncertainty about the effects of face masks”

That’s an eye-opening transition from 2011 to the pandemic version. And it’s down to the decision to reduce the 2020 update to randomized trials only, ditching a body of useful complex data about a very complex intervention. It sent a powerful message into a heated controversy, and people used it to claim masks didn’t work.

It actually requires quite a lot of evidence to prove something doesn’t work, though – and that’s especially so when there’s a good rationale for the intervention, as there is with face masks reducing the transmission of airborne disease.

A key takeaway from this case is that a systematic review isn’t an inevitable good in a controversial question. There’s a responsibility to weigh interpretations of limited bodies of evidence extremely carefully – even more so when it’s obvious the interpretation will be weaponized. We have to stop acting as though systematic reviews are a neutral good. They can be dramatically beneficial or harmful, and everything in betweeen.

A final, and very critical point, before moving on from the “systematic evidence” part of the chain. We cannot afford to just let all the complex pandemic-related questions lie around unresolved, just because they are difficult, we are sick of the controversies, and we want to move past the pandemic and get back to the other questions. If we do that, we set the world up with a mess of “before” evidence, when the next pandemic hits. All of these simmering issues that people are so biased about, they will just come back, as virulent as whatever the next virus is the next time this happens.

I talked about needing to tie these questions up down the line when the major flood of Covid-19 studies is over. That’s going to be an extraordinarily onerous and difficult task, and it needs the time and cool heads of non-emergency pressure to be done well. We need a cache of systematic reviews that can have broad support, and will be front and center in the future.

One of the people attending the talk pursued this particular suggestion with me afterwards. Helen Pearson was working on a feature for Nature on this topic – it was published a few weeks later – and what I said in my talk and our conversation was touched on there and in the accompanying editorial.

She wanted to know, what exactly did I mean about how this would work? I think it needs to be at the trusted commission level for the complex public health interventions. The UK did that many years ago with mammography screening, pulling in impeccably credentialed and trusted experts without a stake in a prior position on the question – like Michael Marmot and Doug Altman – to tackle the question. I think it needs to be international, and avoid being captured by other interests that would be seen to compromise the outcome. This is going to be a lot of work, and take a lot of time, but it needs the full metal jacket. Even finding the enormous body of work sprayed across government and university websites, preprint servers, and journals, is going to be daunting. We can’t afford to walk away without it, though. And this brings us to the “skills and methods” part of the chain.

Case 4: Vaccines

Vaccine development was – and still is – stunning, but bias ran totally amok. And as I pointed out in my last vaccine roundup post, we quickly got to the point where the data and developments were so vast, cherry-picking inevitably became the order of the day.

This is where the skills and methods of systematic reviewing can really play to their biggest strength. The skills and methods helped me enormously – I couldn’t possibly have kept on top without them. But it required adaptation to the specifics of this complex situation. And there were lots of duplicative trackers and databases that I felt suffered from not doing that.

I found myself developing my own resource – a collection I’ve been maintaining publicly in Zotero. Given how long I’ve complained about duplication, I didn’t expect to be doing that, that’s for sure! But there a few reasons. Early on, the WHO’s international clinical trial register basically crashed. They’ve been developing a new platform that can handle the high load of traffic, but it’s not here yet. And in any event, it doesn’t update daily. If you wanted to keep up with developments internationally, and I did, then you had to establish an extensive searching system. And you needed to be going to all sorts of resources to be accurate in what you compiled.

As well as international blind spots early on especially, trackers and databases were often quite slow. And there would be errors, like recording a trial as being in phase 3, when a combined phase trial was registered – even though it would be months till the trial reached phase 3 (with no guarantee, of course, that it ever would).

But the biggest problem was the traditional silo approach to types of evidence: a database of registered primary studies here, of systematic reviews there. When what was needed to be on top of what was going on was something else – a lot of use of so-called “grey literature” (like drug companies’ websites) to be precise and up-to-date about primary preclinical and clinical studies, organized by vaccine, not by study type, and fielding the proliferation of preprints (often the same one in multiple servers) and publications emerging after preprints.

With literally hundreds of vaccines in development, that wasn’t simple. Linking which preclinical study and trial was associated with which vaccine was often a lot harder than you probably imagine, when vaccines didn’t have names, and individuals and organizations were involved with multiple vaccines. I spent more time on the linking of documents and threads of information than I did on the searching. (And there hasn’t been a day since quite early in 2020 that I didn’t run searches.)

When it all settles down, of course, the silo-ed information will be invaluable – but the databases tend to be quite “dirty”, and I fear people will just have to re-do searches from the ground up anyway.

So we reach the last separate issue, that nevertheless is linked to the others: the harm that individuals can do. Many were shocked, I think, when some of the highest profile proponents of systematic evidence became high-profile advocates for a range of contrarian views – at times, denying the seriousness of the disease or outbreaks, or casting doubts about the value of this or that public health action (or even pretty much of all of them). And as they got into deeper trouble over it, they clung harder, digging deeper, and often adding new contrarian strings to their bow.

I’m not going to go into all that here. I’m going to focus here on the “what next?” issues this raises. Firstly, it emphasized that charisma and skill at bashing evidence you don’t agree with is a dangerous combination. The community, including the evidence community, is far too susceptible to charismatic personalities. We need to each develop our individual immunity to it: it makes us susceptible to not seeing how biased a framing of evidence is.

Secondly, there’s a norm among scientists, too, that I think did real damage. That’s using the moment an issue relevant to their work is in the spotlight, to plead for more research funding to their area.

In the pandemic, that played out into, in effect, casting doubt on whether we knew enough to take action, by communicating “we’d be able to give you answers if only you’d fund our work”. It wasn’t in the public interest. For me, it sharpened the need for us to get far more serious about non-financial conflicts of interest.

Indeed, as the financial interests of vaccine developers was also in sharp relief, I came increasingly to question what difference there is between someone needing their or their colleagues’ positions to be assured by sales of something, or by grants. The research work on conflicts of interest has been dominated by academics – and I think one of the results has been resistance, and even blind spots, to academics’ biases. For systematic reviews, we need to develop the knowledge base for recognizing, preventing, and detecting authors’ biases.

When I consider the schema I’ve drawn below, I think the research base and training about bias concentrates mostly on the horizontal stream here – research and analytical skills, and science communication and literacy/critical appraisal skills. We don’t talk anywhere near enough about those on the vertical: values and integrity, and cognitive skills.

It doesn’t matter how advanced or sophisticated our technical skills are if we aren’t aware of, and able to constrain the impact of, the cognitive biases we all have as human beings.

Scott Lilienfeld and colleagues published a paper I think is hugely important in 2009. And unfortunately, I think their conclusions about cognitive de-biasing still hold:

[We] have made far more progress in cataloguing cognitive biases than in finding ways to correct them.

We need a broader approach to the question of risk of bias in systematic reviewing – and we need to build personal bias minimization skills. And that, counter to the trends many are espousing, means slowing down. The faster you go, the more free rein you’re giving your biases.

Balaz Aczel and colleagues point out that deeply internalizing the importance of our cognitive biases requires us to develop skills to head them off when they de-rail our thinking and decisions, recognize when we need to call on our de-biasing skills, and then exercise enough self-control to deploy them. It’s not second nature, and it’s not easy. But it’s at least as essential as spotting statistical bias.

Finally, if you want to avoid becoming just as bad as some of the people you’ve seen getting things badly wrong in the pandemic, take critics seriously and resist getting defensive. You need to recognize when you’re wrong, and I think practising admitting it in every context you can helps. Like skills generally, this one gets easier the more you do it.

I’m very grateful to the organizers of Virtually Cochrane for inviting me to give this talk, and to the participants whose questions and feedback also helped me think through these issues.

Other relevant posts at Absolutely Maybe:

A Cartoon Guide to Criticism: Scientist Edition

Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses: A 5-Step Checkup

Science Heroes and Disillusion

~~~~

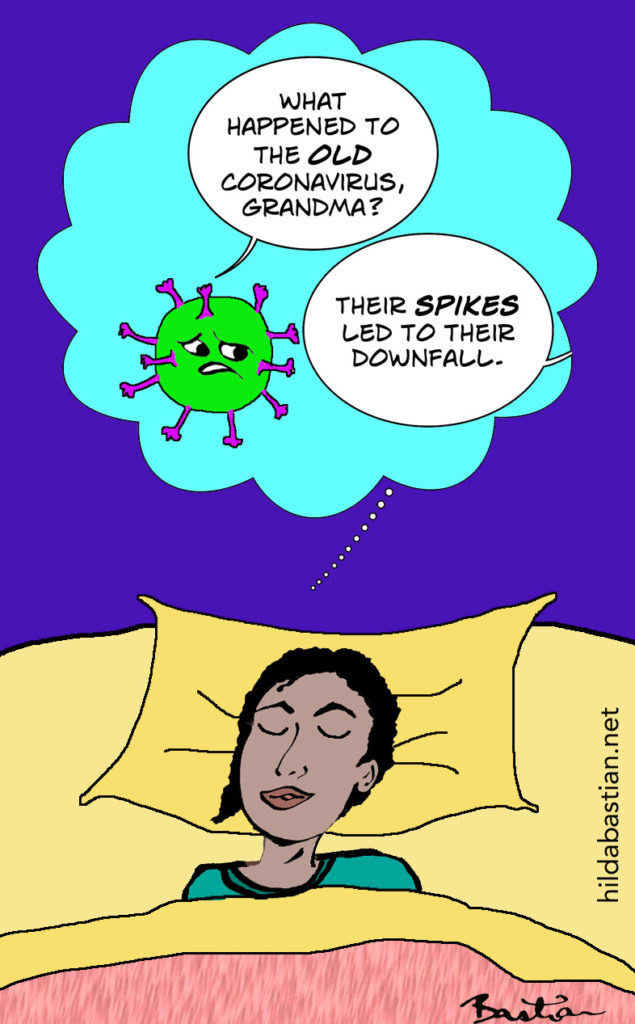

The cartoons are my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny.)

Disclosures: I have been writing about Covid-19 extensively, including criticizing some prominent systematic review(er)s. I’m a consultant to Cochrane on stakeholder engagement for a high-profile controversial review (exercise and ME/CFS). I initiated and introduced the original plain language summary element of Cochrane reviews, and I was a member of the GRADE Working Group when the Summary of Findings table was developed. I studied methodological aspects of shifting evidence that affect the reliability of systematic reviews for my PhD, including several studies of Cochrane reviews. I am one of the founders of the Cochrane Collaboration, although I have not a member of the organization for many years.

These are the references for my talk at Virtually Cochrane, on 22 April 2021:

Systematic Evidence and the Covid-19 Stress Test: Pass or Fail?

SR = systematic review

Case 1 – Convalescent plasma:

- SR 2015: Mair-Jenkins

- August 2020 FDA emergency use authorization evidence base

- SR 2020 (the “before” evidence): Devasanapathy

- SR 2020 (Cochrane living review): Chai

- January 2021: RECOVERY trial press release

- SR 2021: Janiaud

- 2021 (“convalescent plasma hesitancy”): Casadevall

- The Epistemonikos database

Case 2 – Hydroxychloroquine:

- June 2020: RECOVERY trial press release

- SR 2020: Siemieniuk

- My rapid response to the Siemieniuk SR at BMJ

Case 3 – Masks:

- My blog post at Absolutely Maybe looking at the SRs in April 2020

- SR 2020 (Cochrane): Jefferson

My public Zotero database linking data sources on Covid vaccine trials.

De-biasing: Lilienfeld 2009

At Absolutely Maybe: A Cartoon Guide to Criticism – Scientist Edition.

Hilda Bastian

22 April 2021

This list was originally posted here at a discontinued website.